The Dallas Museum of Art is currently at T-minus 11 days until the opening of our new exhibition, Bouquets: French Still-Life Painting from Chardin to Matisse. Floral still-life paintings are arriving from across North America and Europe, and Bouquets will open to the public on Sunday, October 26, 2014 (DMA Partners will have a chance to see the exhibition a few days earlier during the DMA Partner Preview days on October 23-25).

As a curator of this exhibition, I’ve already had several people ask me how I became interested in this rather specialized subject. I will confess straightaway that it is not because I have any particular skill in growing flowers (sadly, the contrary), identifying flowers (I have a shockingly bad memory for names, of both plants and people), or arranging flowers (even the most elegant bouquet from the florist becomes an awkward muddle when I’m entrusted with the task of transferring it to a vase). So, I did not enter into this exhibition with the belief that I had any special insights into the world of flowers to share.

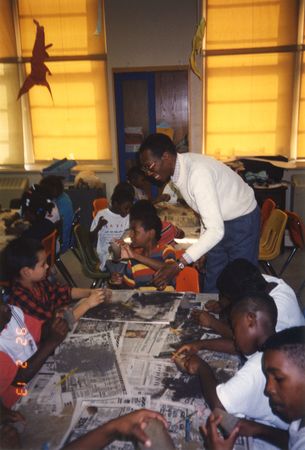

Rather, I was brought to the exhibition by the DMA’s art collection. In some cases, we decide to pursue an exhibition because it allows us as curators to share with our audiences art that is not represented in depth in our own collection. This was the case with J.M.W. Turner in 2008 or Chagall: Beyond Color in 2013; however, there are also moments when we create exhibition projects as a way to showcase particular strengths of our collection and build a major research project around our own masterpieces. This was the case with Bouquets.

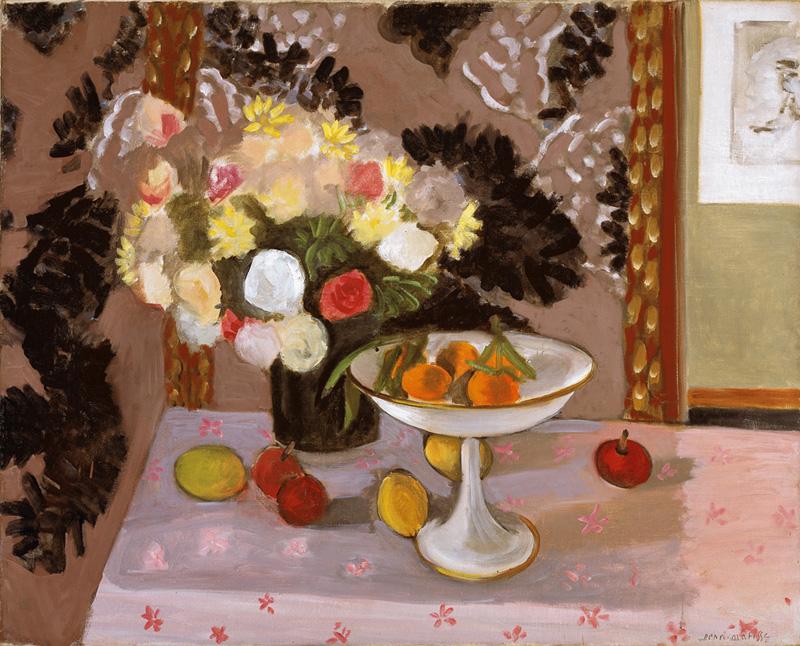

Several years ago, I was approached by my co-curator, Dr. Mitchell Merling of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, with an idea for an exhibition of French floral still-life painting. He wanted the exhibition to focus on the table-top still life and the bouquet, and was starting to build a list of possible works to include. Did the DMA have many paintings that fit that description, he asked? By the time I finished rounding up all the works that fit the bill, I went back to Mitchell and told him that I hoped to partner with him in curating the exhibition. Not only did the DMA have more than a dozen works of art that met the criteria, but quite a number of them were also masterpieces of our European art collections. These included important (and incredibly beautiful) paintings by Anne Vallayer-Coster, Henri Fantin-Latour, Edouard Manet, Gustave Caillebotte, Paul Bonnard, and Henri Matisse. I knew that this exhibition would be an invaluable opportunity to give these paintings the kind of visual and scholarly context they so richly deserved. Luckily, Mitchell agreed with me, and we set to work on crafting the exhibition together.

Bouquets includes six important paintings from our collection, making the DMA the largest single lender to the exhibition. In addition to these works that will travel with the exhibition to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond and the Denver Art Museum in 2015, we have also included two additional still lifes from our collection just for the show’s presentation in Dallas—the more the merrier! Although there wasn’t room to include all of our French floral still-life paintings in the exhibition, you can see several others elsewhere in the Museum.

For instance, in Mind’s Eye: Masterworks on Paper from David to Cézanne (on view until October 26, 2014, the same day that Bouquets opens), you can see a major pastel, Flowers in a Black Vase, by the inventive symbolist artist Odilon Redon. Redon is featured in Bouquets with three paintings, but because of the length of the exhibition tour we were not able to include any of his ethereal and fragile pastels. In Flowers in a Black Vase, Redon crafts one of his most sumptuous and darkly beautiful bouquets, a perfect floral tribute for the Halloween season:

Odilon Redon, Flowers in a Black Vase, c. 1909-10, pastel, Dallas Museum of Art, The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection

When you visit our galleries of European art, you’ll see that in the place of Fantin-Latour’s Still Life with Vase of Hawthorne, Bowl of Cherries, Japanese Bowl, and Cup and Saucer, featured in Bouquets, we’ve brought out another painting, Flowers and Grapes, by the same artist. This meticulously composed autumn still life was one of the first paintings in the collection selected for treatment by Mark Leonard, the DMA’s new Chief Conservator, even before his Conservation Studio was opened last fall. The jewel-like tones of the chrysanthemums, zinnias, and grapes in the newly cleaned painting now positively glow on our gallery walls.

Henri Théodore Fantin-Latour, Flowers and Grapes, 1875, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated

And, finally, in the Wendy and Emery Reves Galleries on Level 3, be sure not to miss a special display of one of our smallest and most unpretentious bouquets, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Bouquet of Violets in a Vase. Painted when the artist was just 18 years old, this still-life reveals the potent influence of Manet on the young artist, as well as Lautrec’s own precocious talent. This small panel painting, usually displayed in the Library Gallery of the Reves wing, where it is difficult for visitors to appreciate, is currently on view in an adjacent space where it can be enjoyed up-close, alongside another early painting by Lautrec.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Bouquet of Violets in a Vase, 1882, oil on panel, Dallas Museum of Art, The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection

Flowers are in bloom throughout the Museum this October, and there is no better time to fully appreciate the depth, importance, and sheer beauty of the DMA’s collection of European still-life painting.

Heather MacDonald is The Lillian and James H. Clark Associate Curator of European Art at the DMA.