Surrealism is typically regarded as an art movement dedicated to personal exploration by tapping into a person’s subconscious. This was certainly an important component, but Surrealism was also focused on group activity, ranging from the creation of Surrealist journals, to collectively written statements, to unfettered discovery through group play and games.

Surrealism is typically regarded as an art movement dedicated to personal exploration by tapping into a person’s subconscious. This was certainly an important component, but Surrealism was also focused on group activity, ranging from the creation of Surrealist journals, to collectively written statements, to unfettered discovery through group play and games.

Many of the games the Surrealists played together were derived from the types of parlor games they learned as children or still enjoyed as leisure. Such activities, while fun, were also meant to spur creativity and subvert the psychological conditioning of society. Sometimes these games resulted in finished works of Surrealist art and writing. As the movement’s self-proclaimed leader, André Breton, described their game playing in 1954: “Although as a defensive measure we sometimes described such activity as ‘experimental’ we were looking to it primarily for entertainment, and those rewarding discoveries it yielded in relation to knowledge only came later. […] It is clear that to shut oneself off from game-playing […] is to undermine the best of one’s own humanity.” (Brotchie and Gooding, 1991, 137-138)

Perhaps one of the greatest benefits for educators using Surrealist games in the classroom is how the activities offer a set of tools to get learners conceptualizing critically and playing with images, words, and ideas where the purpose is surprise, delight, and creativity. For the Surrealists, the fact that games had rules or instructions that mandated how they were played, but the end-goal was itself unstructured, illogical, and messy, was representative of their own world-view.

Let’s briefly explore two games the Surrealists used in group settings that might be fun to apply to classrooms and museum teaching. My descriptions of these games has been adapted from Alastair Brotchie and Mel Gooding’s delightful Book of Surrealist Games (Shambhala Redstone Editions, 1995).

The Exquisite Corpse

Perhaps the best known Surrealist drawing game, the Exquisite Corpse was actually born out of a writing activity. Surrealism’s roots are in writing and poetry; its earliest practitioners and founders were all writers. Games like the Exquisite Corpse (the name is taken from the poetic results of the first game played) were later modified into a visual variant.

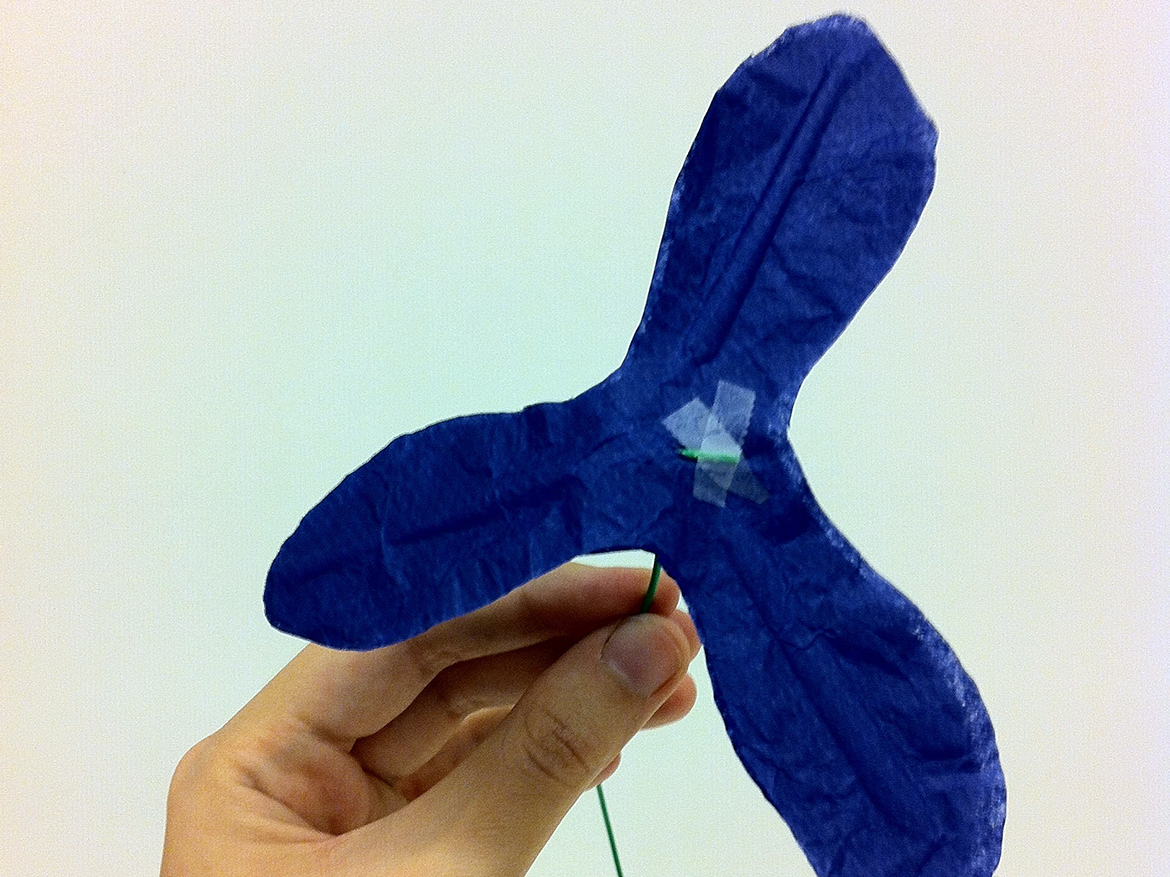

Group size: Typically three-to-four players, or any size up to how easily one sheet of paper can be folded.

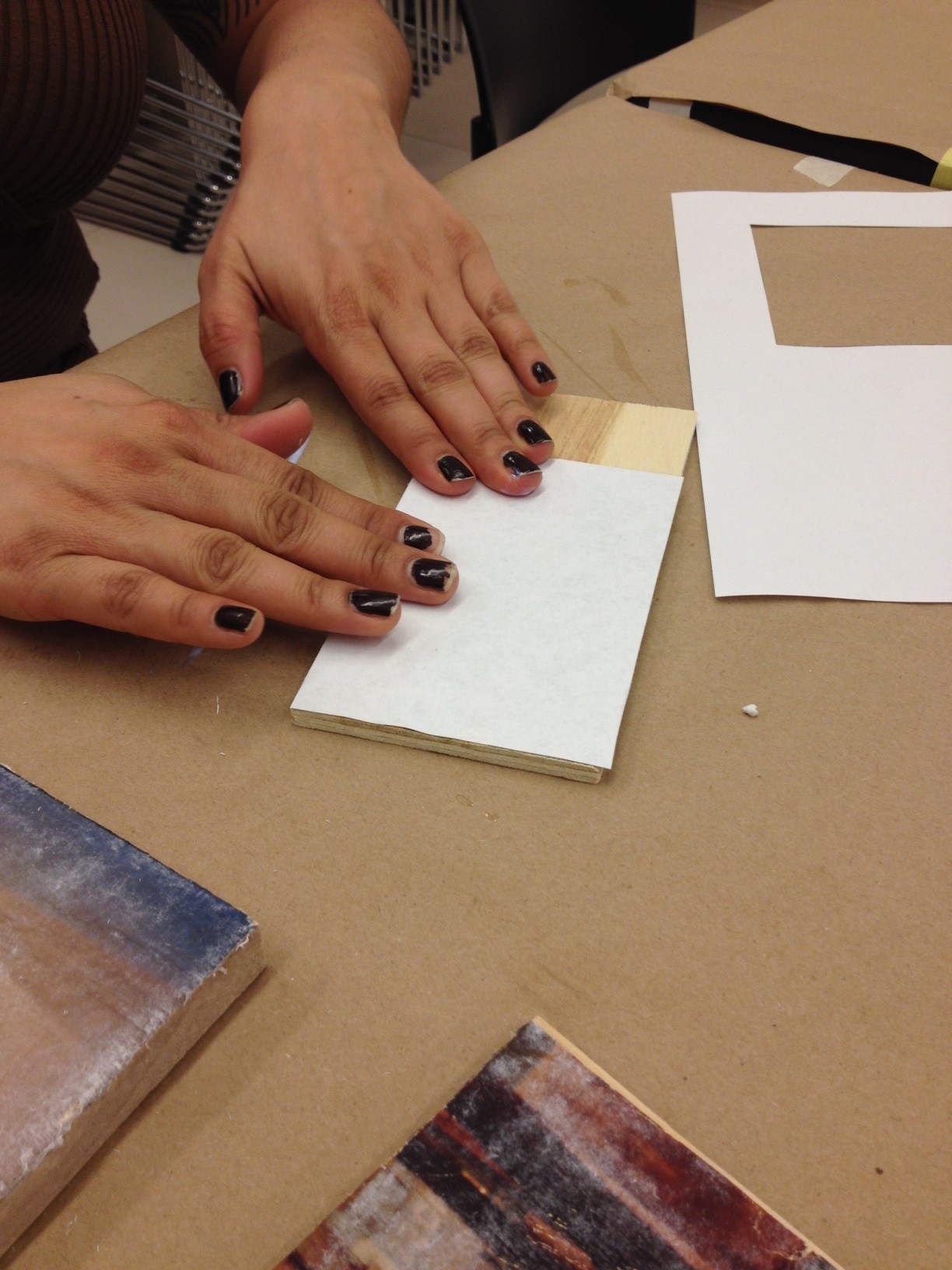

Instructions: A piece of paper is folded so that the number of creased sections matches the number of players, usually horizontally or in quarters for four players.

The first player takes the folded paper with the top fold exposed and draws anything that comes to mind. (Note: In it’s purest incarnation, as a reference to the name of the game, the players are to base their portions of the drawing on the portions of a human body, but this is by no means a hard-and-fast rule!)

She then extends some of her drawn lines across the fold into the next blank section, and refolds the paper so only the second section is exposed, and the next player cannot see what she drew in the first section.

The re-folded sheet is passed to the second player, who bases his drawing on the few exposed lines provided. After completing his section, he also extends a few of the bottom-most lines across the fold, refolds to hide his portion and expose the next, and passes to the next player.

This process continues until all players have a turn to draw a section, when it is unveiled and unplanned, group-designed drawing is revealed. An added variation involves the last player handing the folded drawing to the first player again, who must conceive of a title before the full drawing is shown.

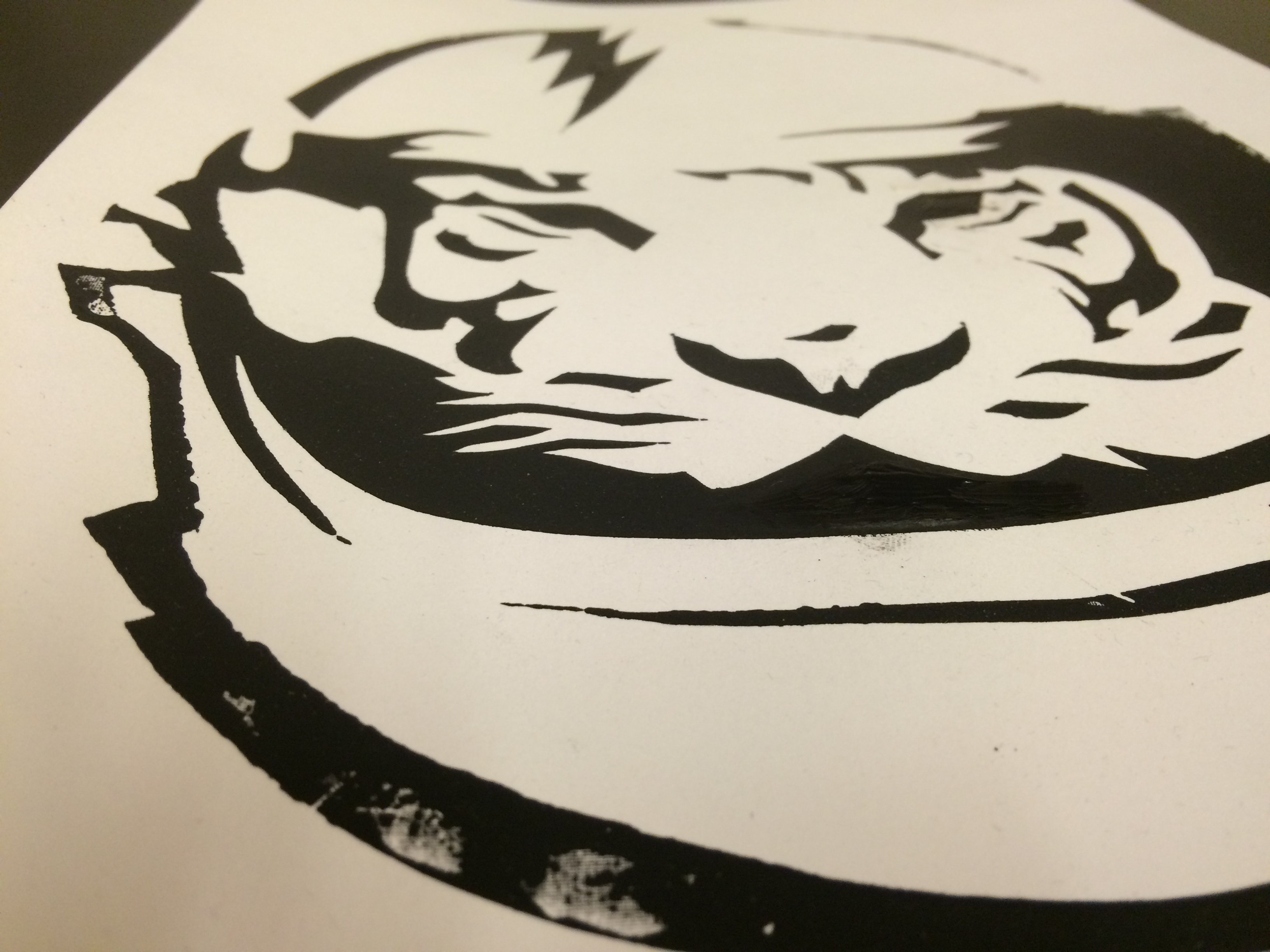

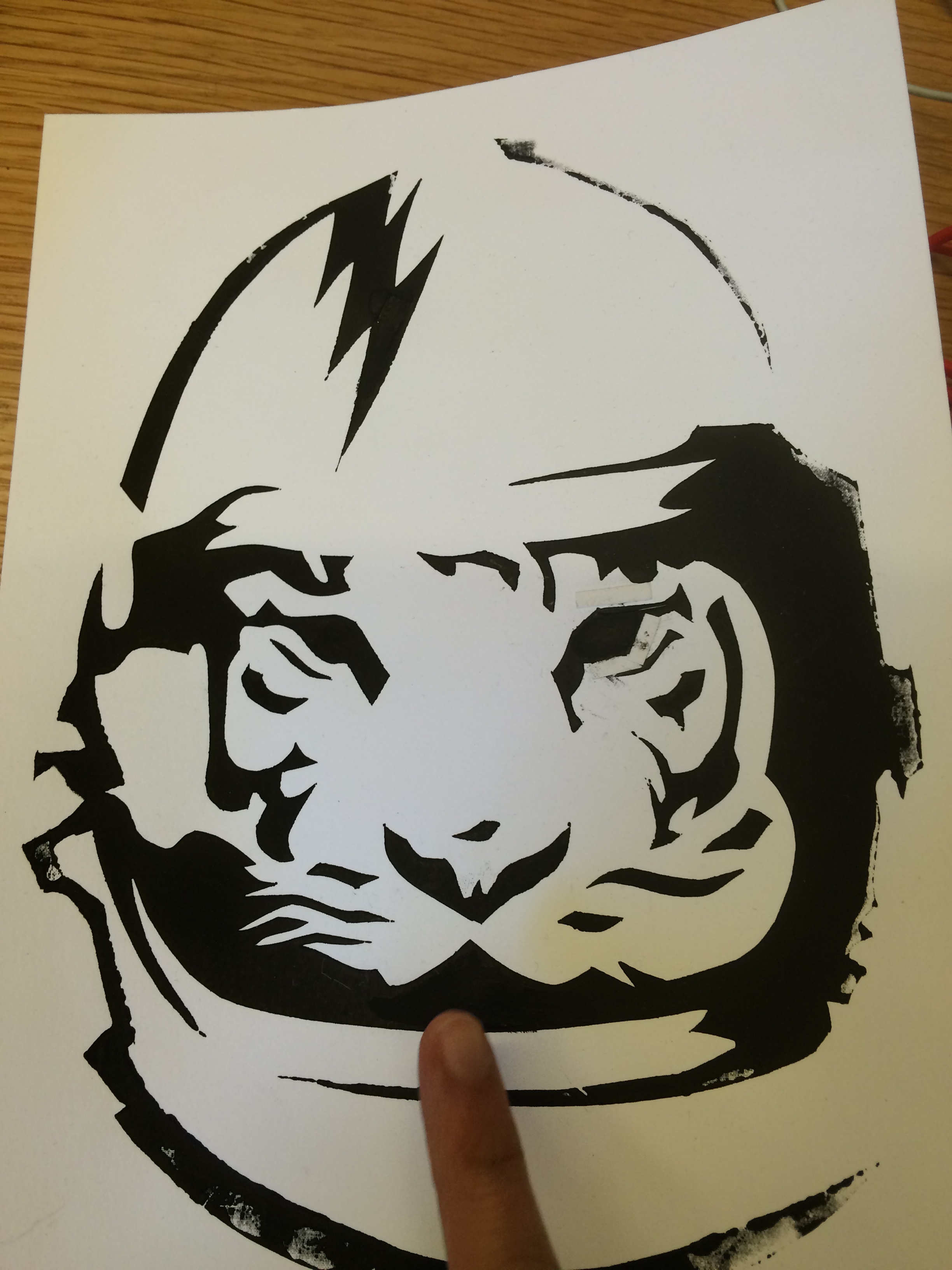

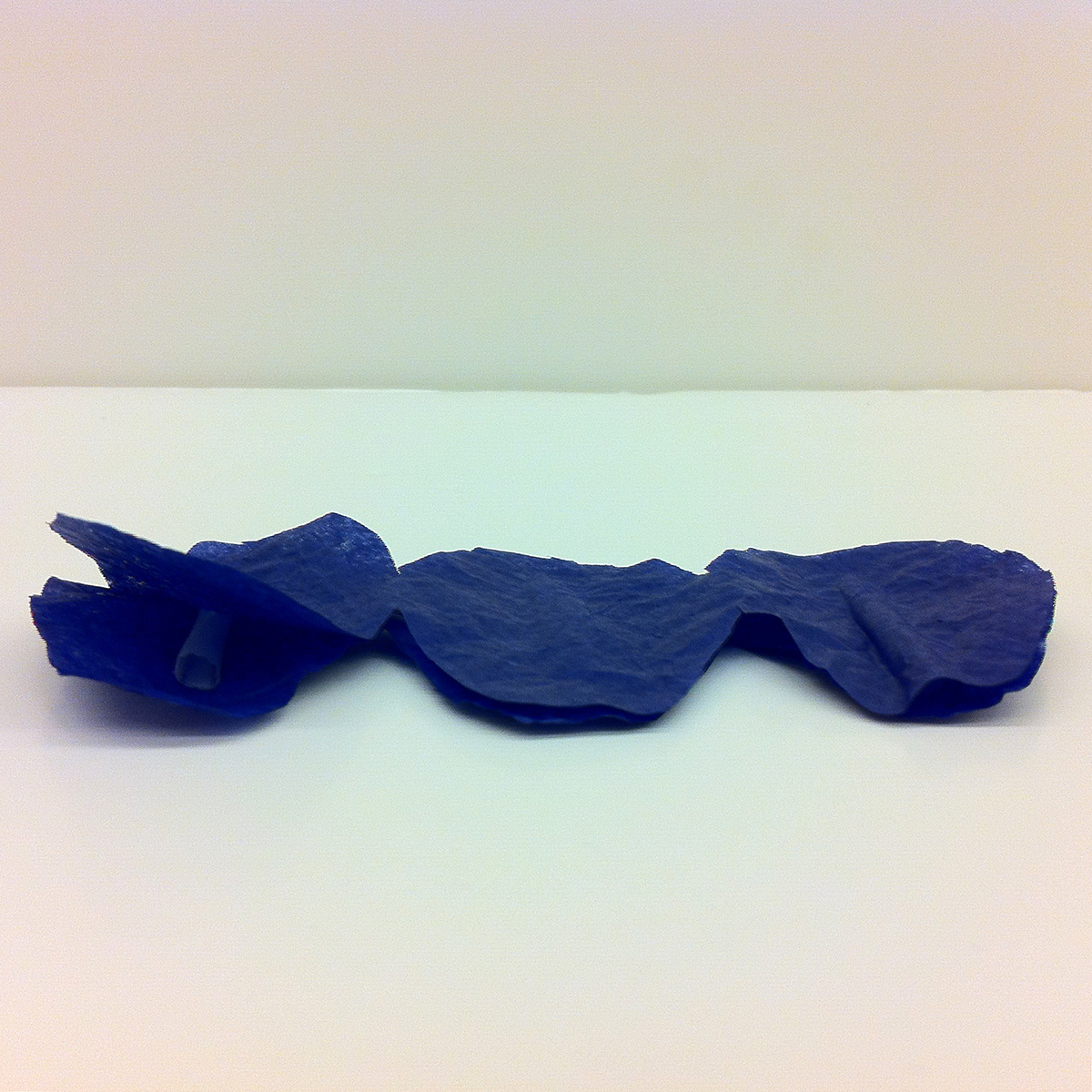

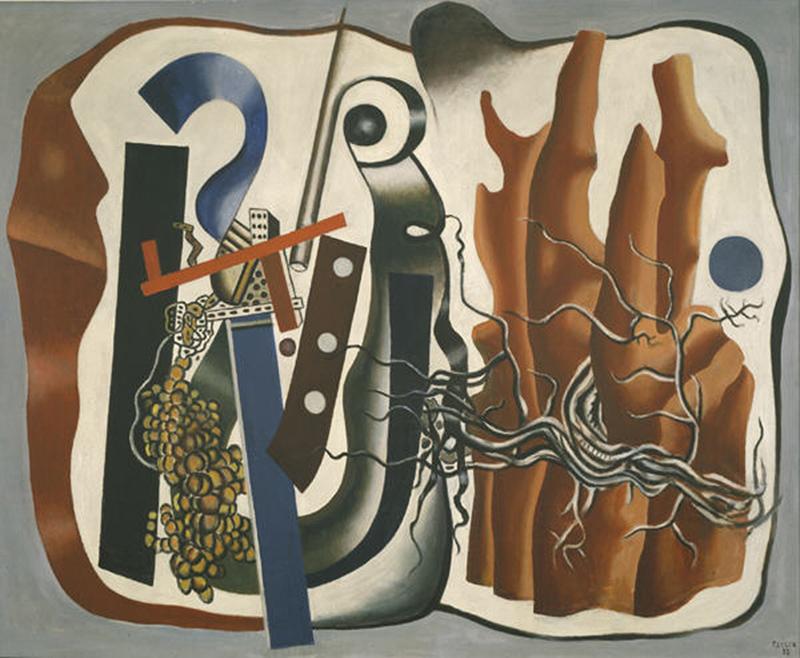

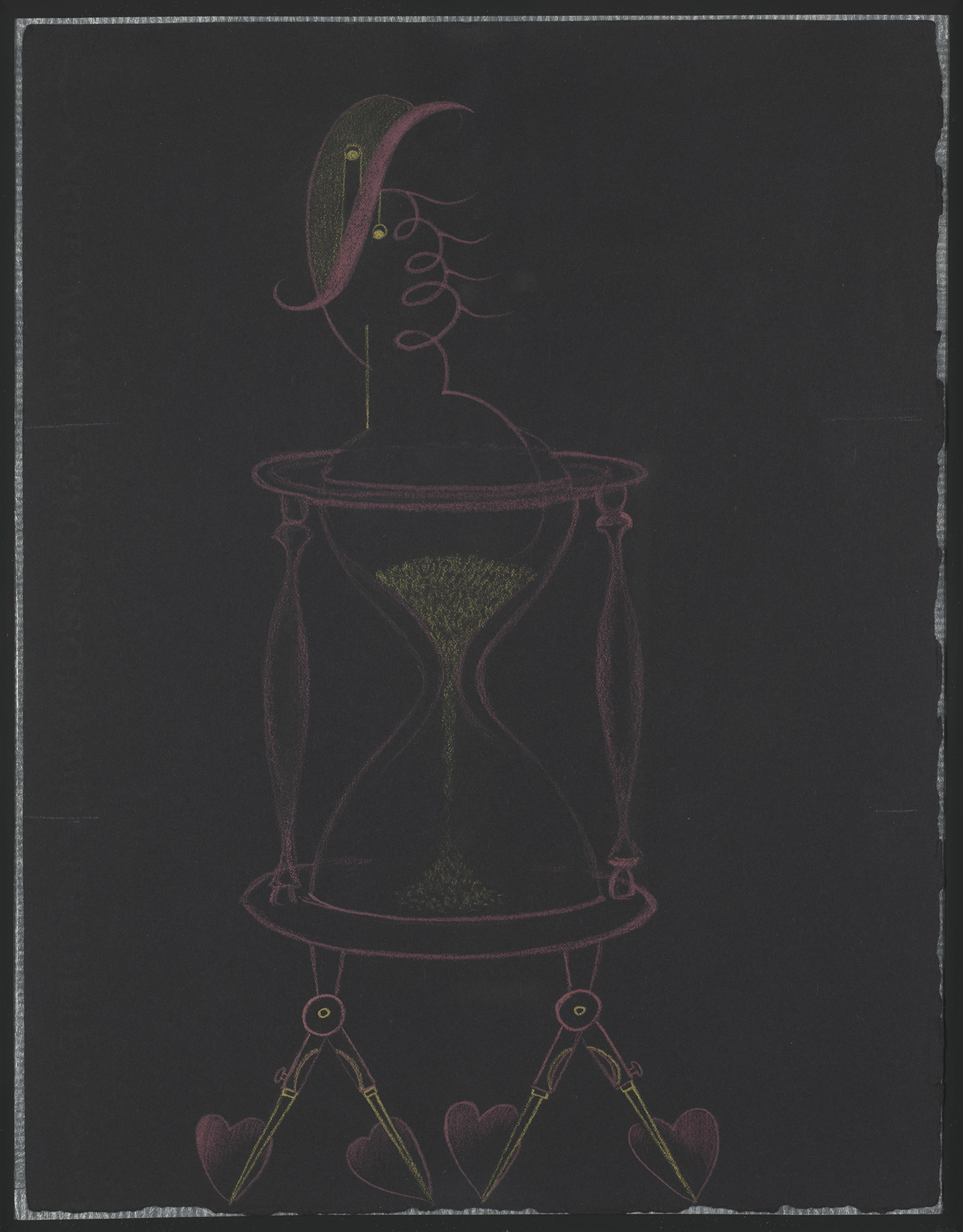

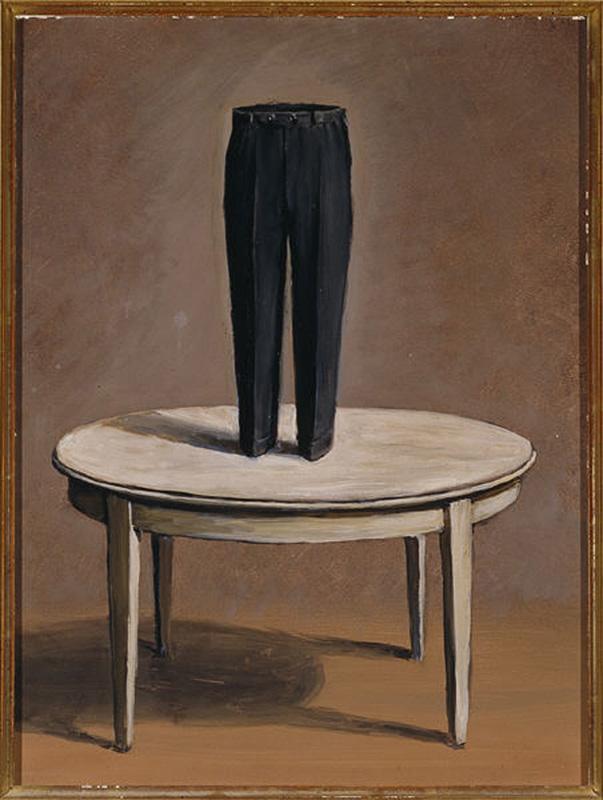

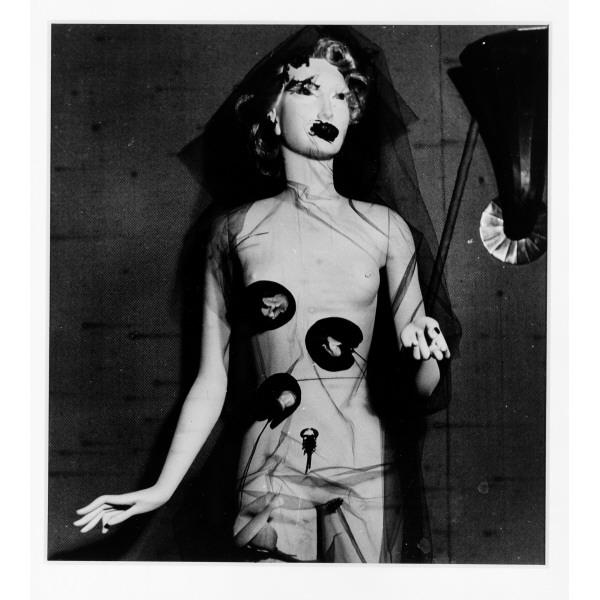

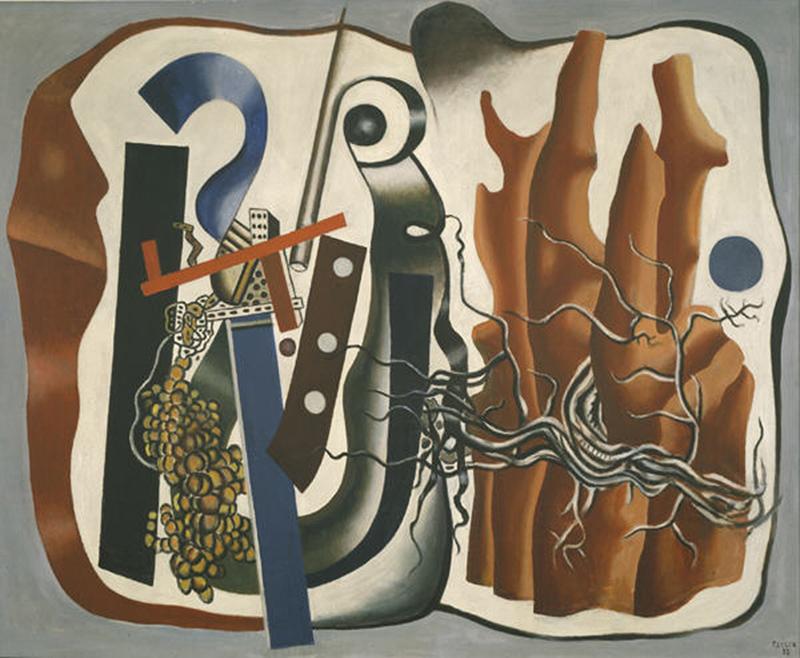

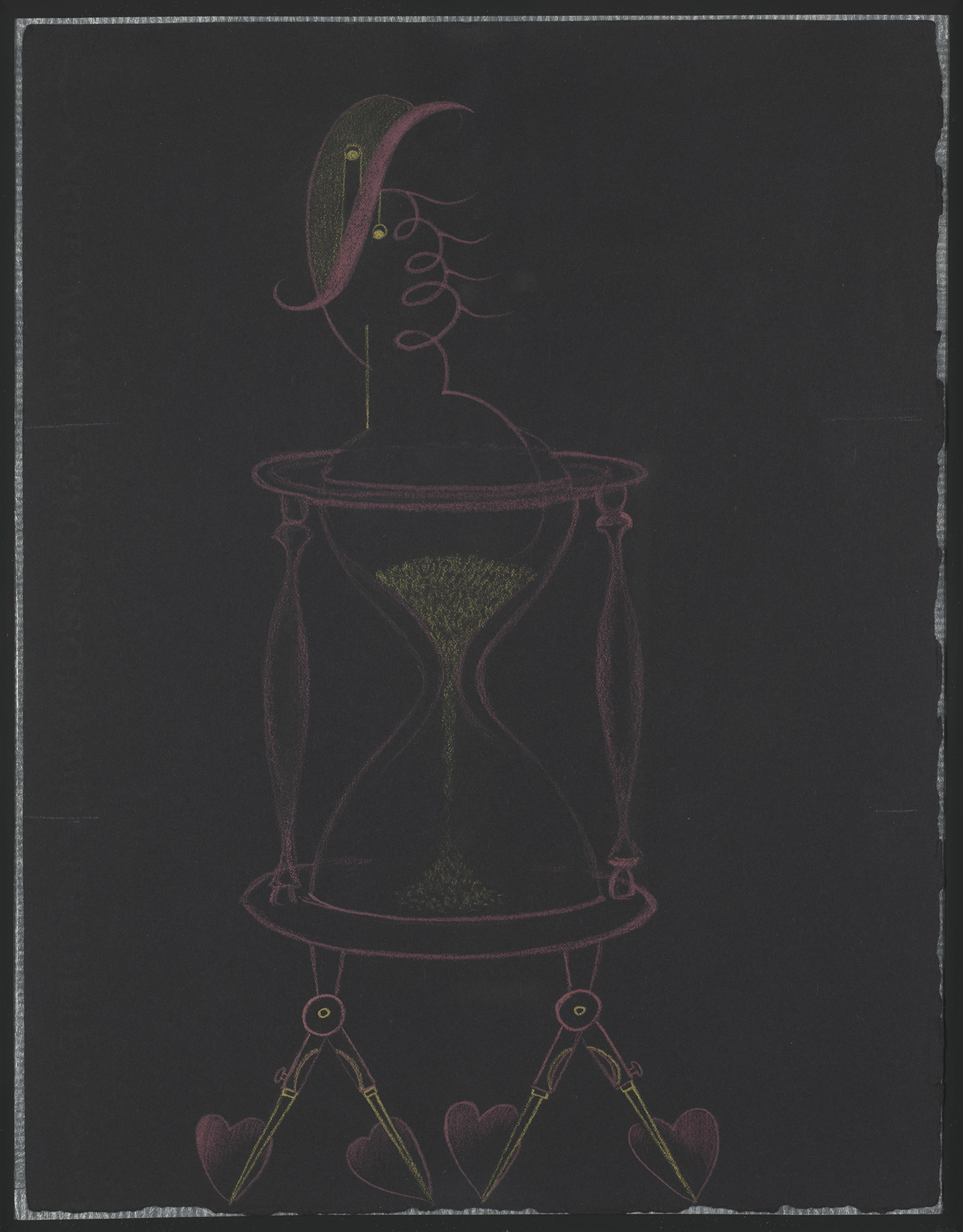

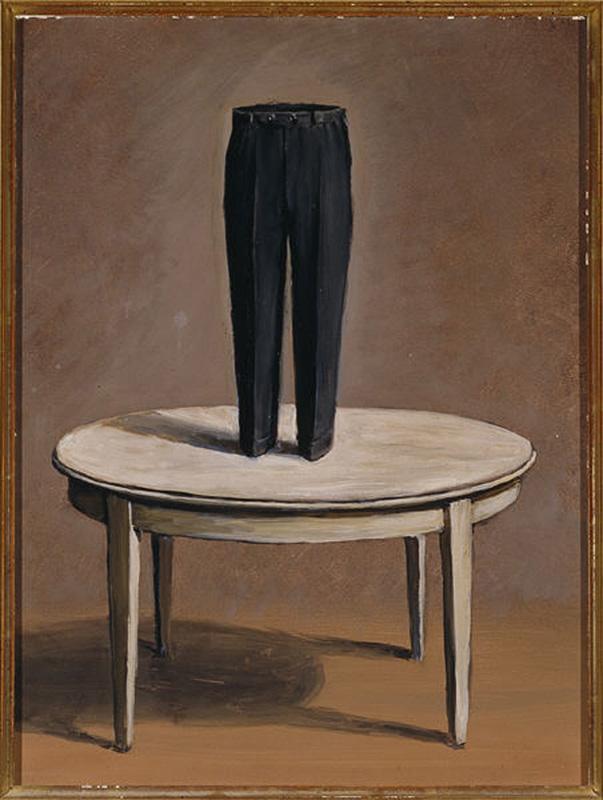

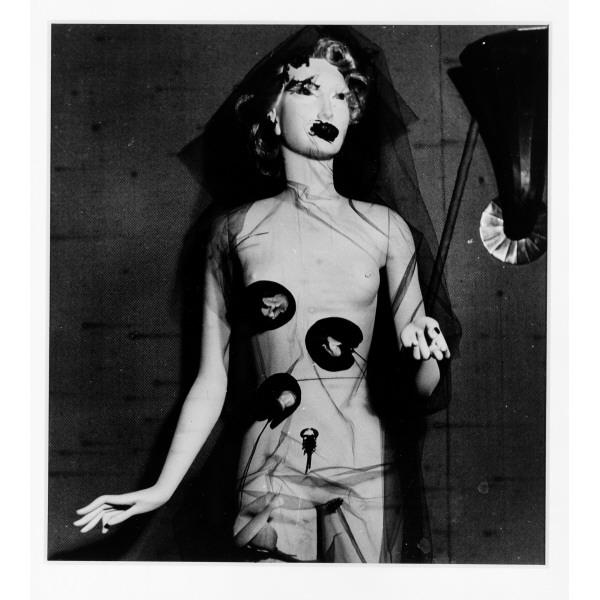

Outcome: An example of an Exquisite Corpse can be seen above, created by André Breton, Greta Knutson, and Valentine Hugo, where the “head” is a florid, calligraphic design, the “torso” is an hourglass, and the “legs” are heart-footed compasses. The surprising and seemingly unnatural conjunctions of objects in these drawings are similar to the visual juxtapositions presented in many Surrealists’ work. Examples include the René Magritte’s Persian Letters, and Surrealist objects, such the one below by Sonia Mossé, both in the DMA’s collection.

The Game of Variants

This is essentially the traditional “whisper” game of Telephone. The group sits in a circle, and the first person conceives of a phrase, then whispers it to her neighbor. The second person whispers the same sentence to his neighbor, and so on, through the entire group. By the end, the beginning and ending phrases are compared.

An example:

Starting Phrase: “You must dye blue the pink bags fathomed by orange parapets.”

Ending Phrase: “At all costs forget the fifth paragraph of ‘Paradise Lost’.”

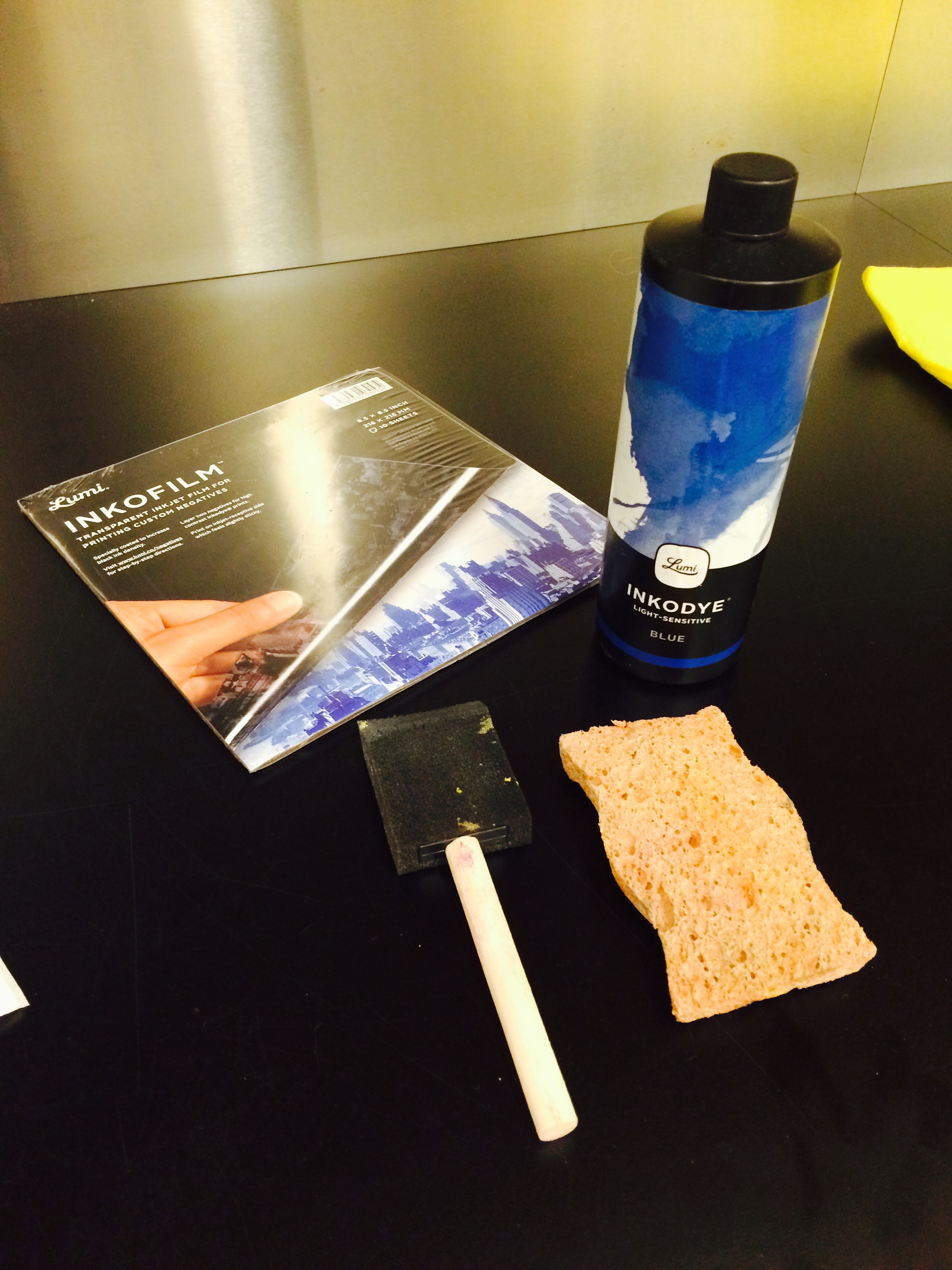

While not practiced by the Surrealists, I have used a fun visual variant of this game in teaching.

Group Size: Best suited for groups between ten and thirty players.

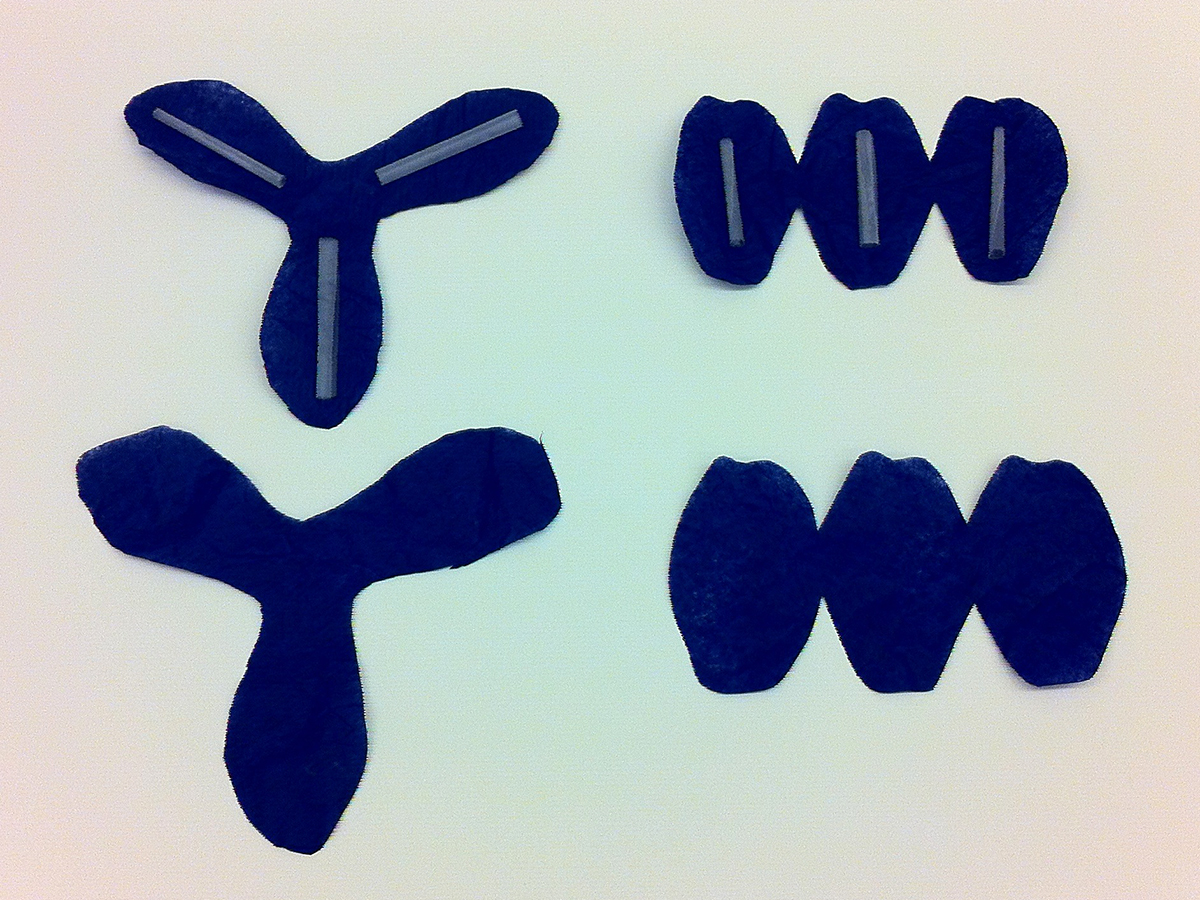

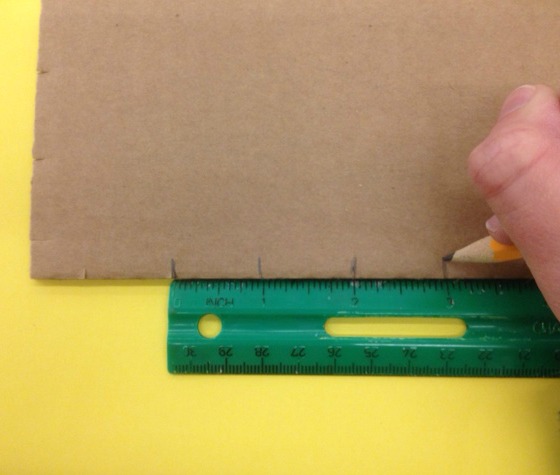

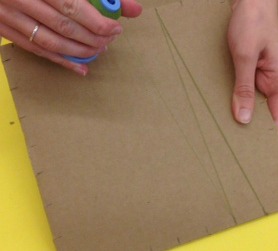

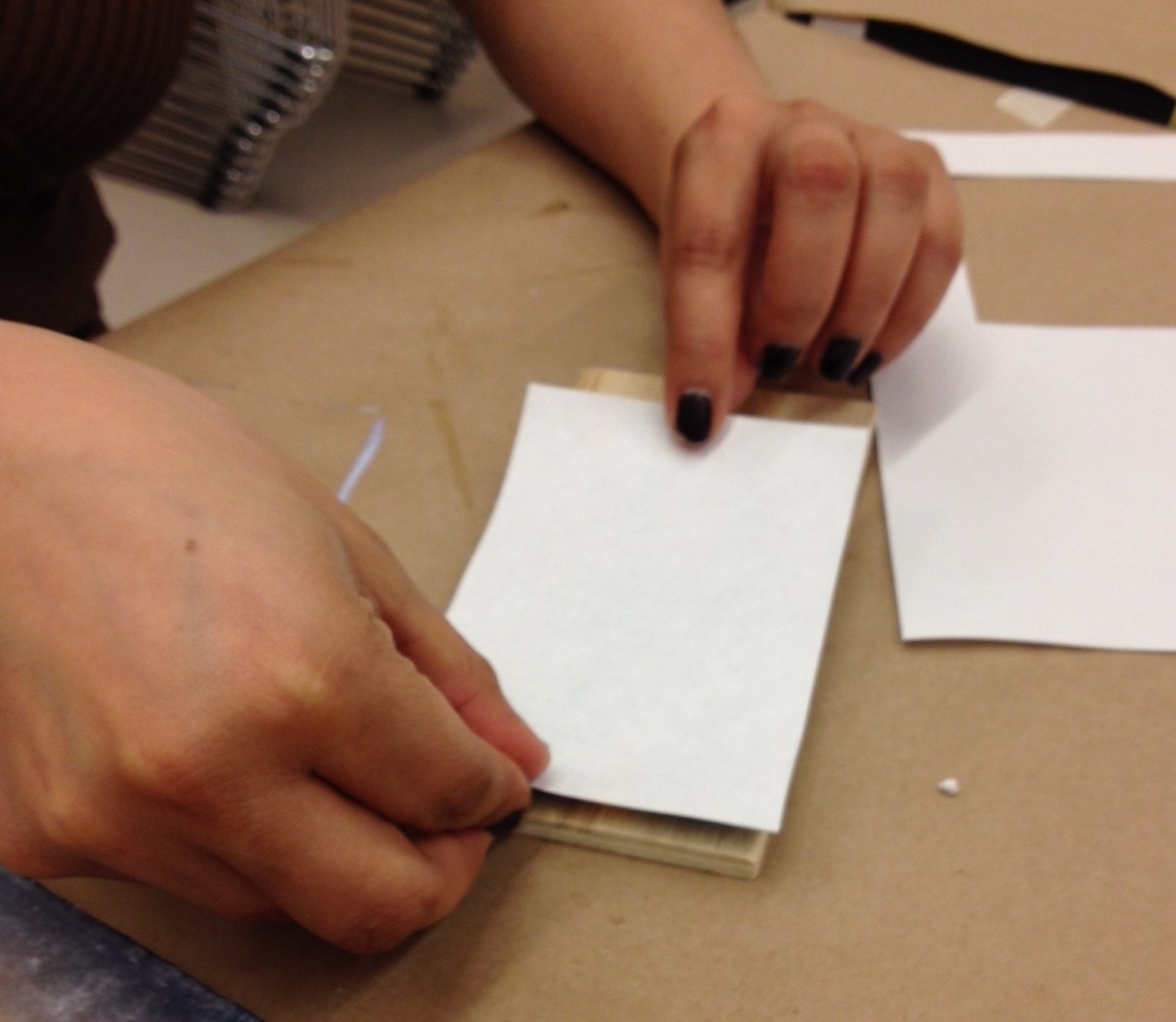

Instructions: Take a piece of paper and fold it horizontally then vertically in an accordion-style (front-over-back) into quadrants that add up to the number of players. (So, with twenty-five players, fold a typical sheet of paper four times horizontally, then four times vertically.)

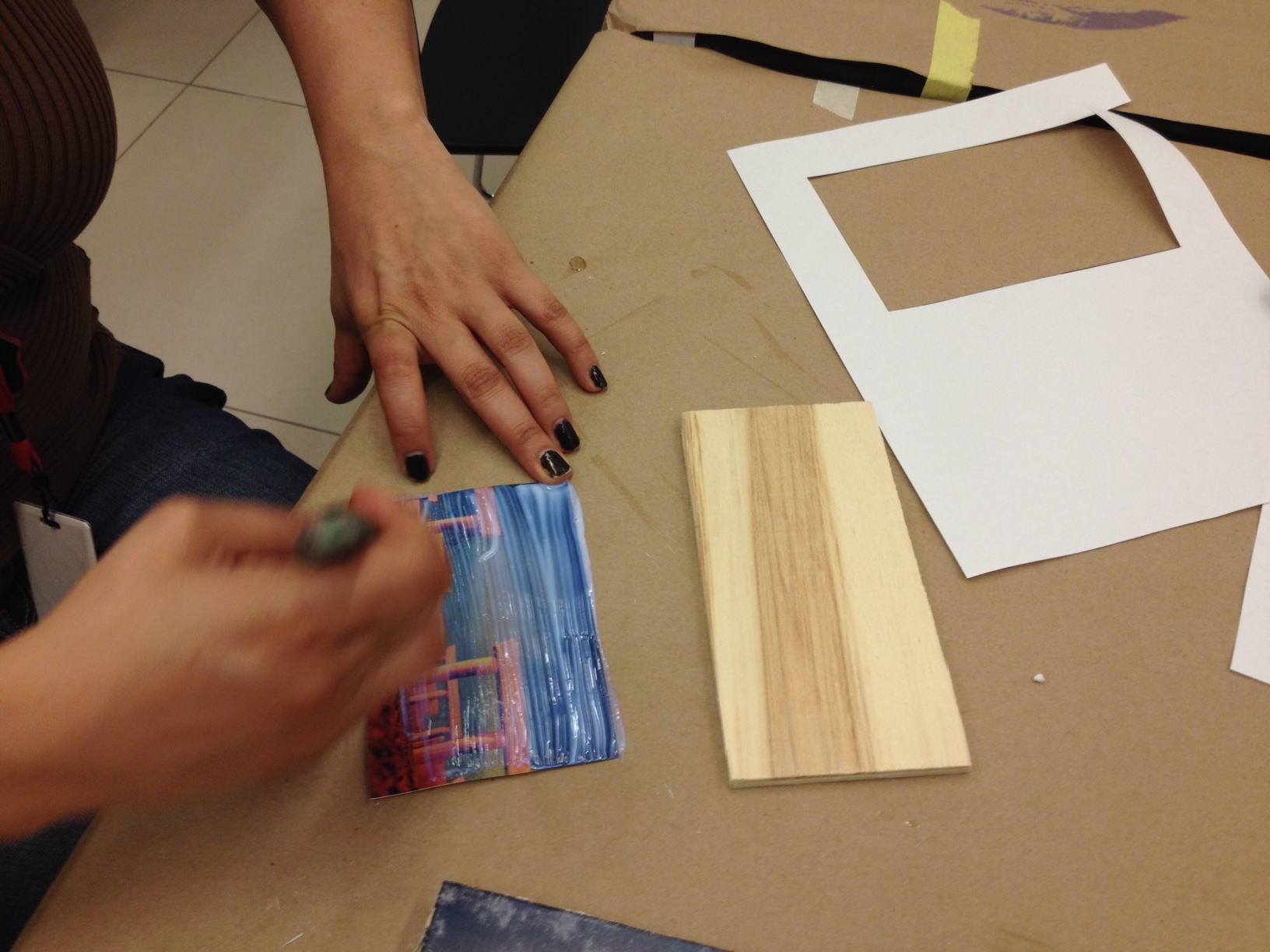

Present the folded up paper so only one folded quadrant is visible, then have the first player draw a small simple, linear image.

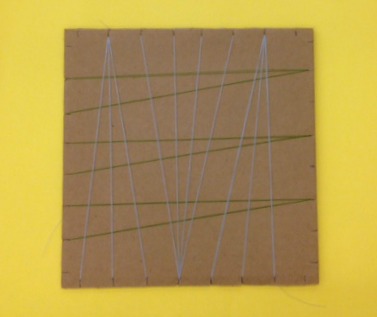

She then presents the drawing to the next player, who looks at it, folds the paper over to the next blank quadrant, then redraws the image from memory. He then passes his version of the drawing on, and the process is repeated until the last player finishes her drawing.

Once finished, unfold the entire sheet, and marvel at the evolution of the image as it transforms from one recognizable thing into something else altogether!

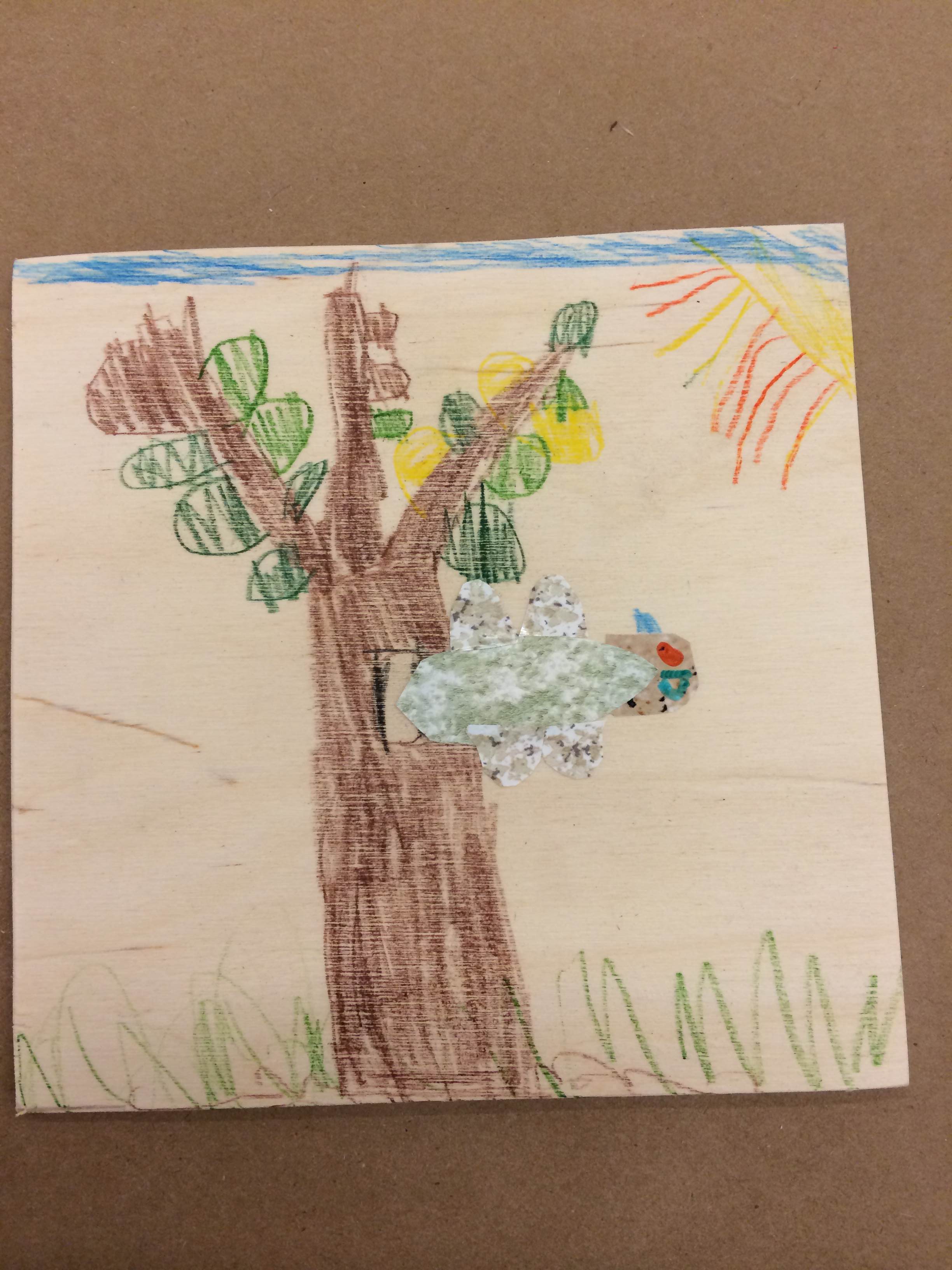

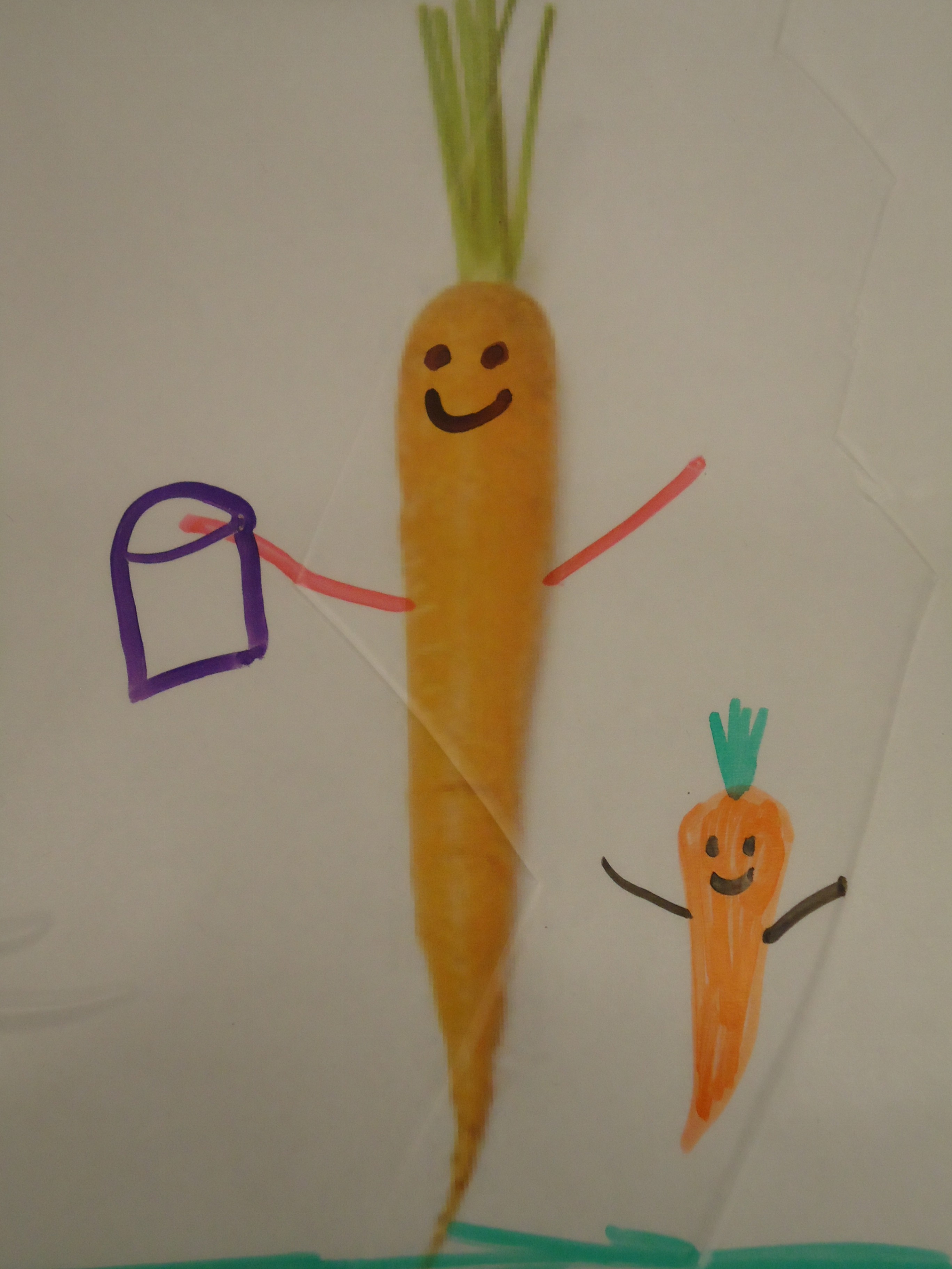

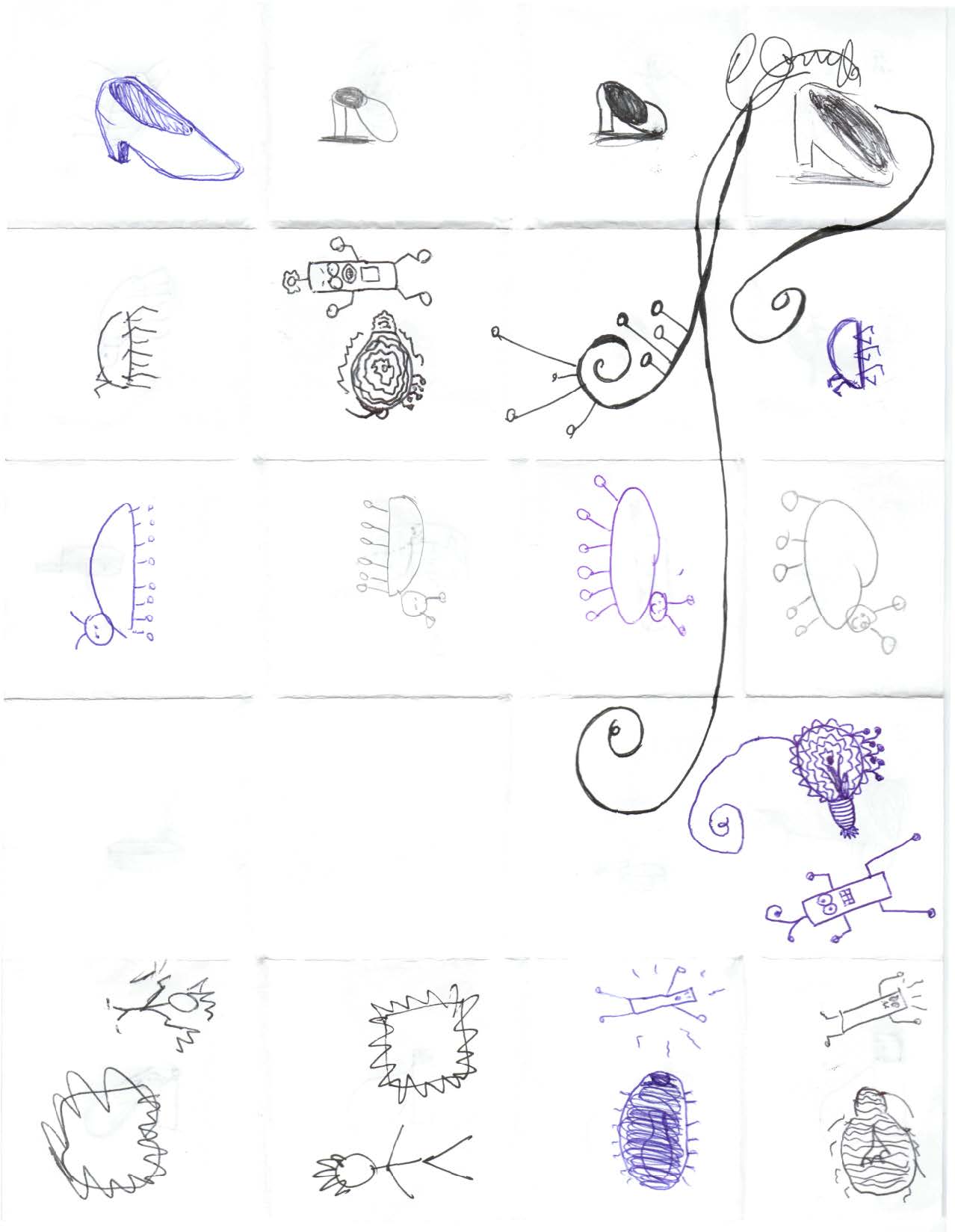

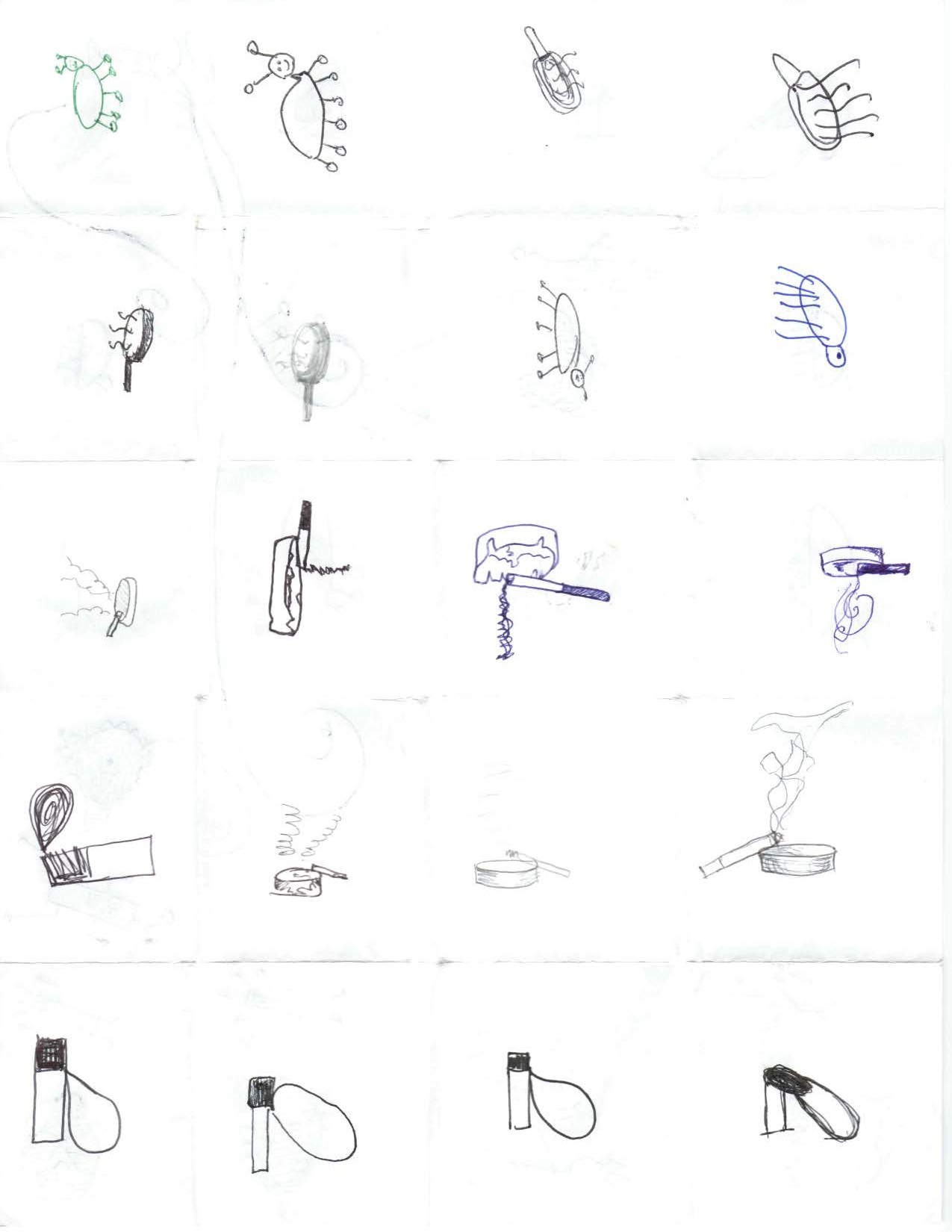

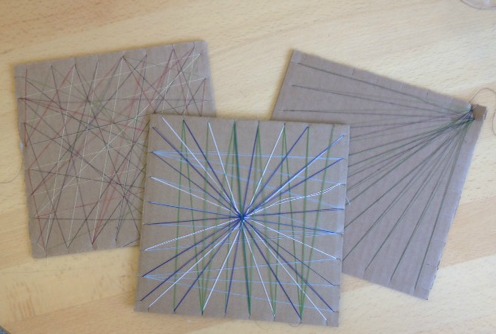

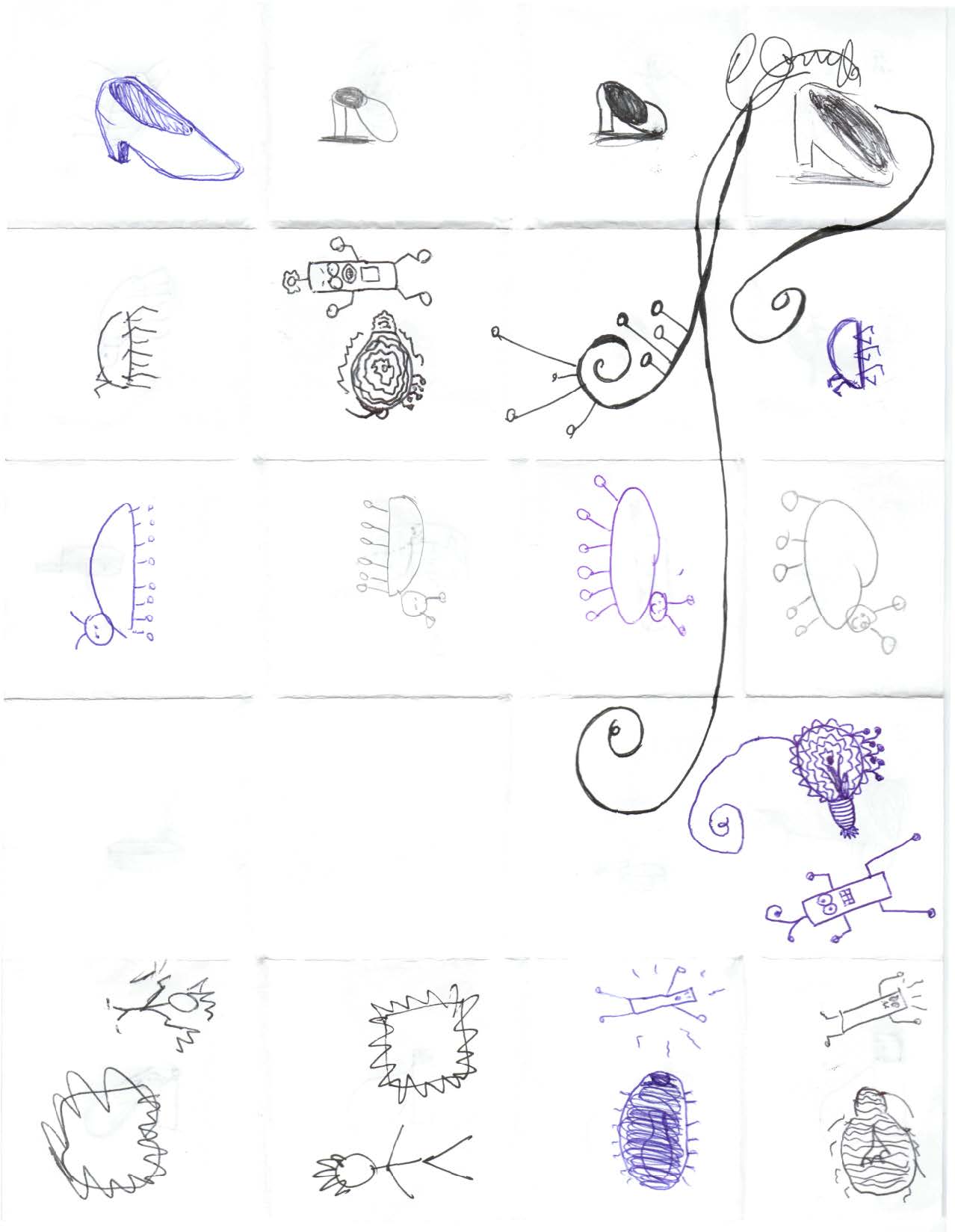

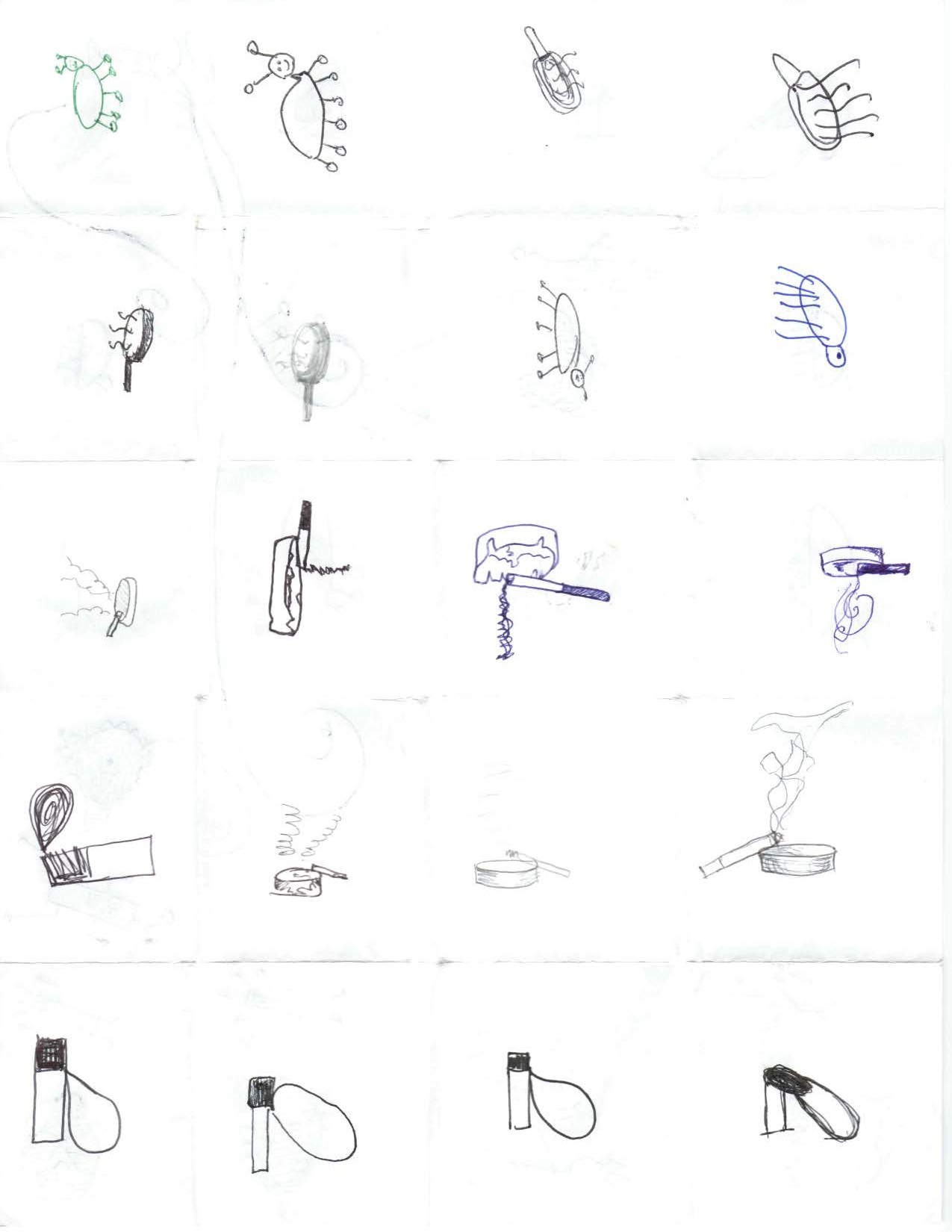

Outcome: Just as the results of the Telephone game are remarkable for the dissimilarity between starting and ending phrases, the results of this visual variant are similarly startling, but the sheet also becomes a visual record of the transformation of starting image into something else entirely. In the example below completed during a class I taught in 2009, the starting image of a shoe transforms multiple times, into a cigarette and ashtray, a frying pan, a robot, and a bug.

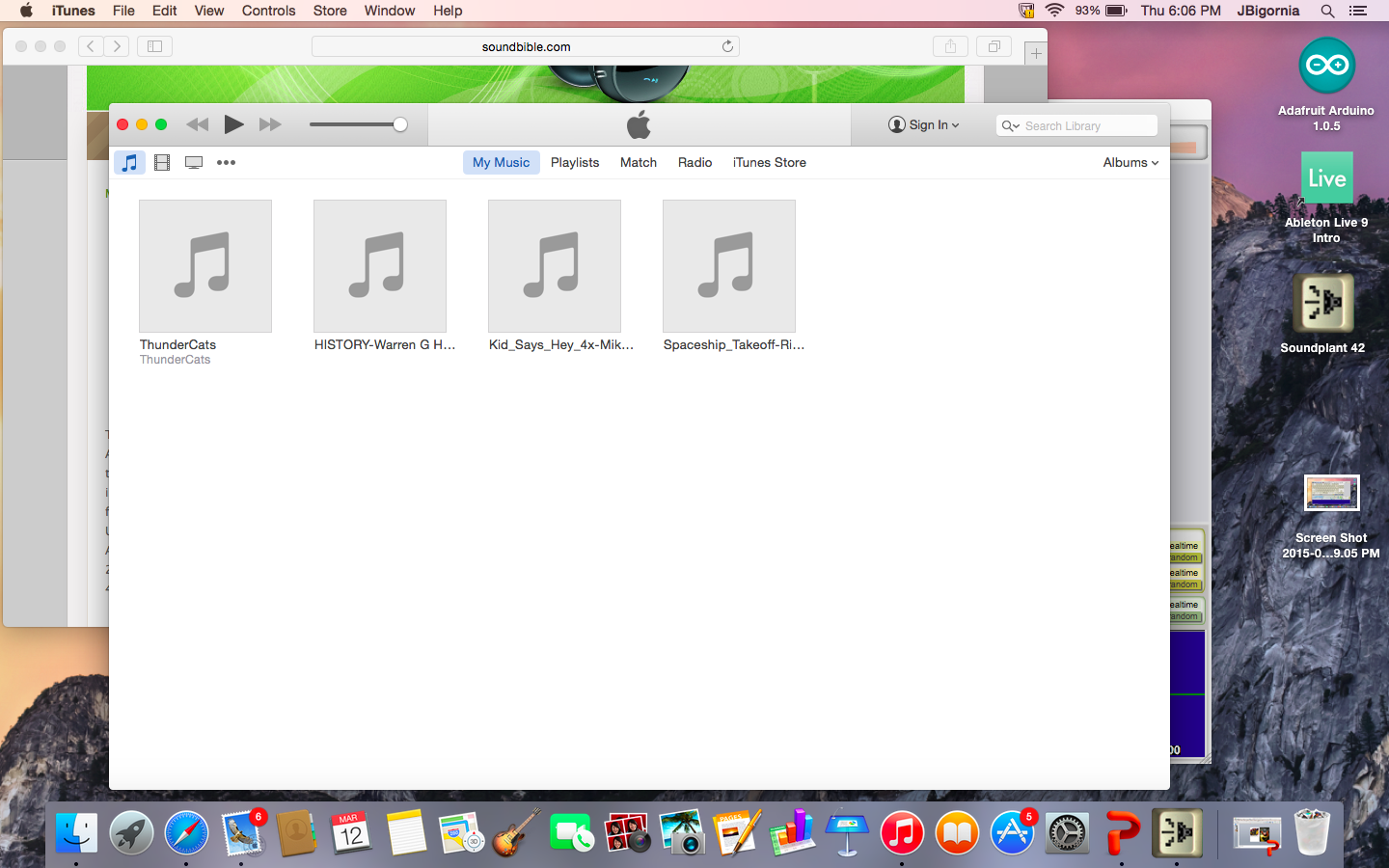

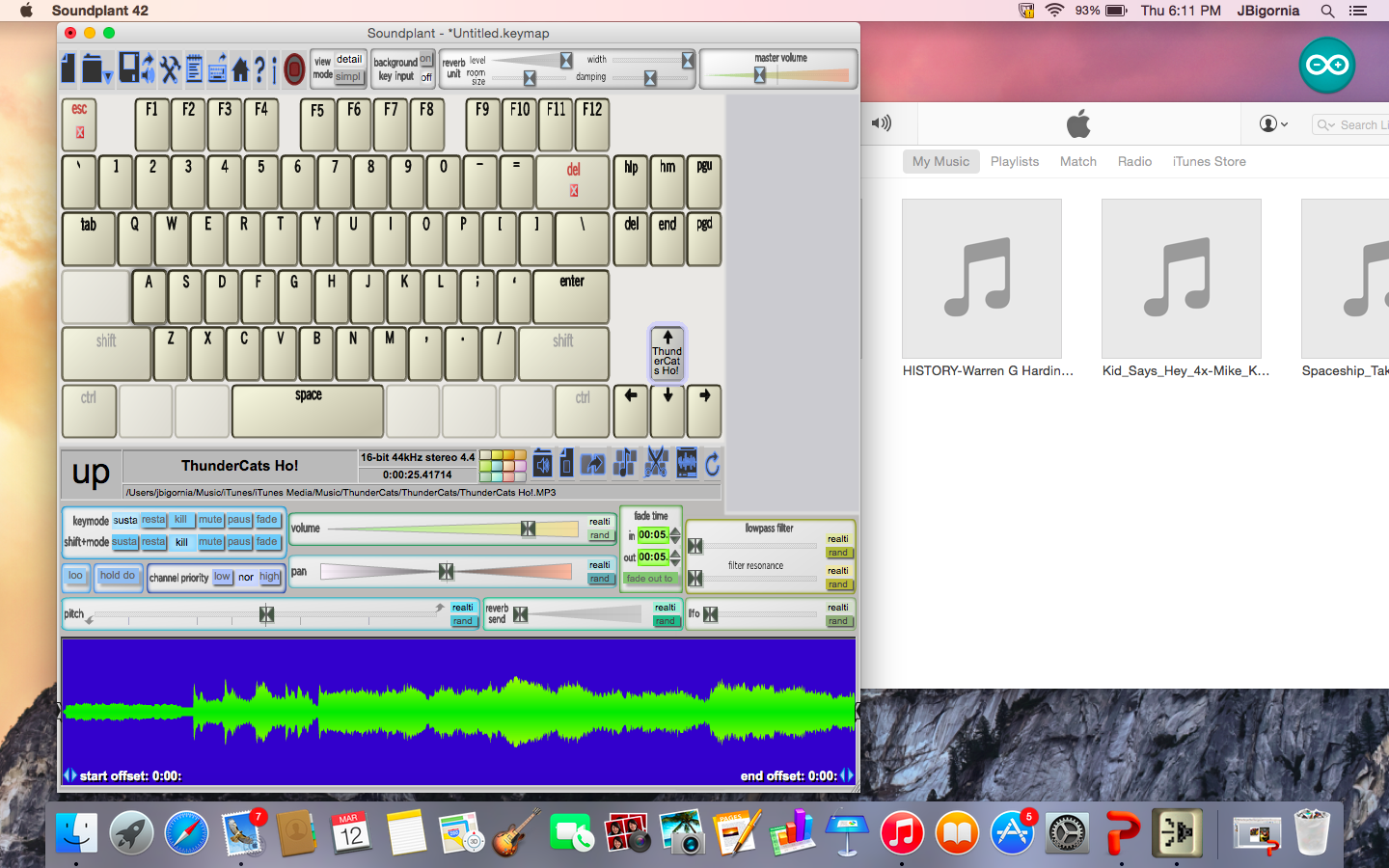

Game of Variants Drawing (recto), 2009

Game of Variants (verso), 2009

Have you tried using Surrealist games like these in your teaching or for fun? Please leave your experiences and ideas in the comments below!

Artworks shown:

- Ferdinand Léger, Composition with Tree Trunks, oil on canvas, 1933, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of the James H. and Lillian Clark Foundation.

- André Breton, Greta Knutson, Valentine Hugo, Untitled (Exquisite Corpse), Colored pencil on black paper, c. 1929, Private Collection.

- René Magritte, Persian Letters, oil on canvas, 1958, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of J.B. Adoue, III.

- Gaston Paris, Untitled (Mannequin by Sonia Mossé), Gelatin silver print, 1938, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Junior Associates and an anonymous donor.

Sources:

Brotchie, Alastair and Mel Gooding. A Book of Surrealist Games. Boston & London: Shambhala Redstone Editions, 1995.

Josh Rose

Manager of Docent and Teacher Programs