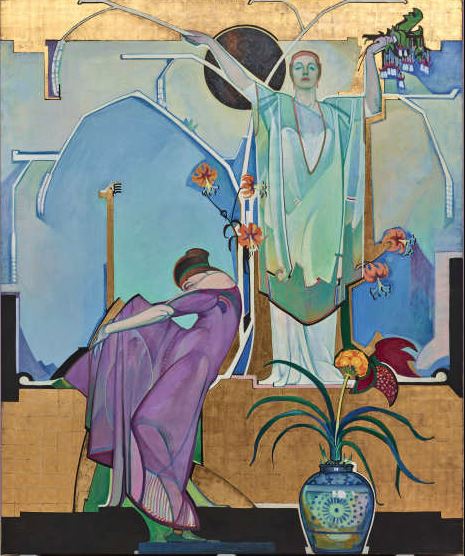

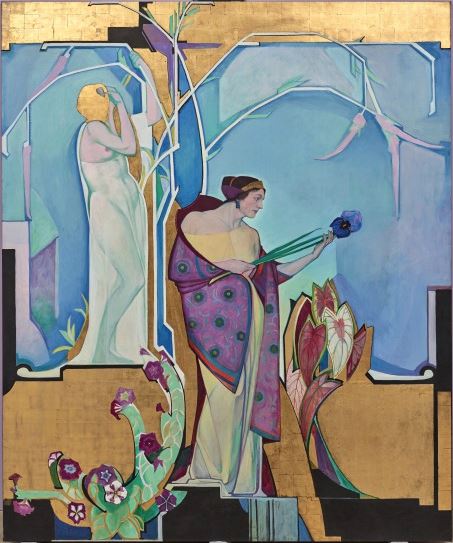

If you’ve visited the DMA lately, you likely noticed the large red mural created by Minerva Cuevas in our Concourse. For those unfamiliar with Cuevas’s art, she is known for her conceptual multi-media installations, and the way her images, language, found objects, and sculpture work together to create political critiques. Some of her projects reformat the visual language of advertisements, using it to harness advertising’s power to affect cultural narratives. For example, see Cuevas’s morbid reimagining of the Del Monte logo. What makes her work so interesting and accessible is the way it explores the relationships among socioeconomic systems, indigenous identity, and the environment with a sense of dark humor. Sometimes, as we see in Fine Lands, her work is downright playful.

Fine Lands, on view at the DMA through September 2, transforms the Museum’s central Concourse into a dystopian Texas landscape, rendered in a powerful comic-book style. Familiar silhouettes of oil wells become menacing, insectlike forms, while crude oil spewing from a derrick morphs into a cloud of bats filling the sky.

Alongside cacti and desert scrub, a tortoise’s shell is reimagined as a backpack, a reference to the northward journeys of migrants. A tough, muscled armadillo and wide-eyed prairie dogs wear bulletproof vests. It’s easy to imagine these critters as comic book characters with individual personalities.

Meanwhile, enormous ants represent industrial and agricultural labor. Echoes of the Texas State Fair’s midway evoke the quintessential cultural icons of Dallas. Framing the mural at one end of the Concourse are the words “LAND LIBERTY LIFE,” a message that is equally evocative of the American dream and of indigenous struggles for autonomy and food sovereignty.

Fine Lands Press Preview, May 11, 2018

This imagery and its layers of associations allow us to imagine unfolding narratives, or to insert our own memories of the Texas landscape. Although the mural clearly references hot-button issues such as pollution, migrant labor, and the power of the fossil fuel industry, there is no single overarching message. Rather, Cuevas holds a mirror up to Texas culture, reflecting it back to us with the added insights that creative metaphor brings. For example, she treats oil in several ways: as a natural resource, as an element of our economy (for better or worse), and as a visually fascinating substance that oozes and seeps across the landscape. More than a simple warning about the dangers of oil as a pollutant, this imagery evokes the role of fossil fuels as the bedrock of Texas industry and an important component of our deep-rooted sense of independence.

Through its examination and reframing of common cultural stereotypes surrounding our state, Fine Lands offers a new way of seeing and understanding subjects such as immigration, the politics surrounding natural resources, and ideas about Texan identity. The presence of bright white crosshairs distributed throughout the mural lends an undertone of menace. The sight of these crosshairs hovering on the wall just ahead implies an immediate threat, lurking right behind us. How we understand that implied threat, and the extent to which we participate in Cuevas’s reflection on the Texas landscape, is up to each of us.

Chloë Courtney is a Digital Collections Content Coordinator at the DMA.