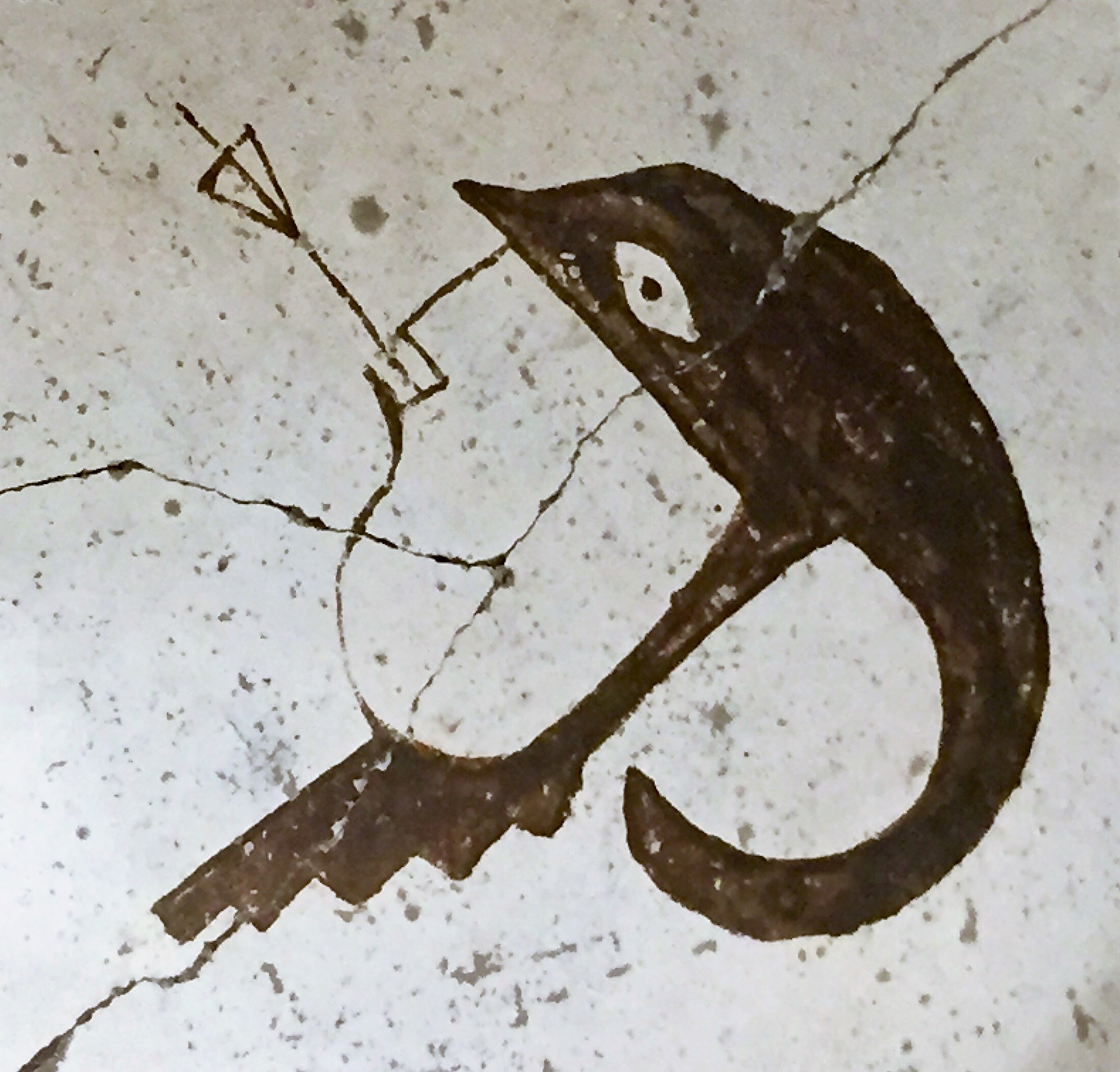

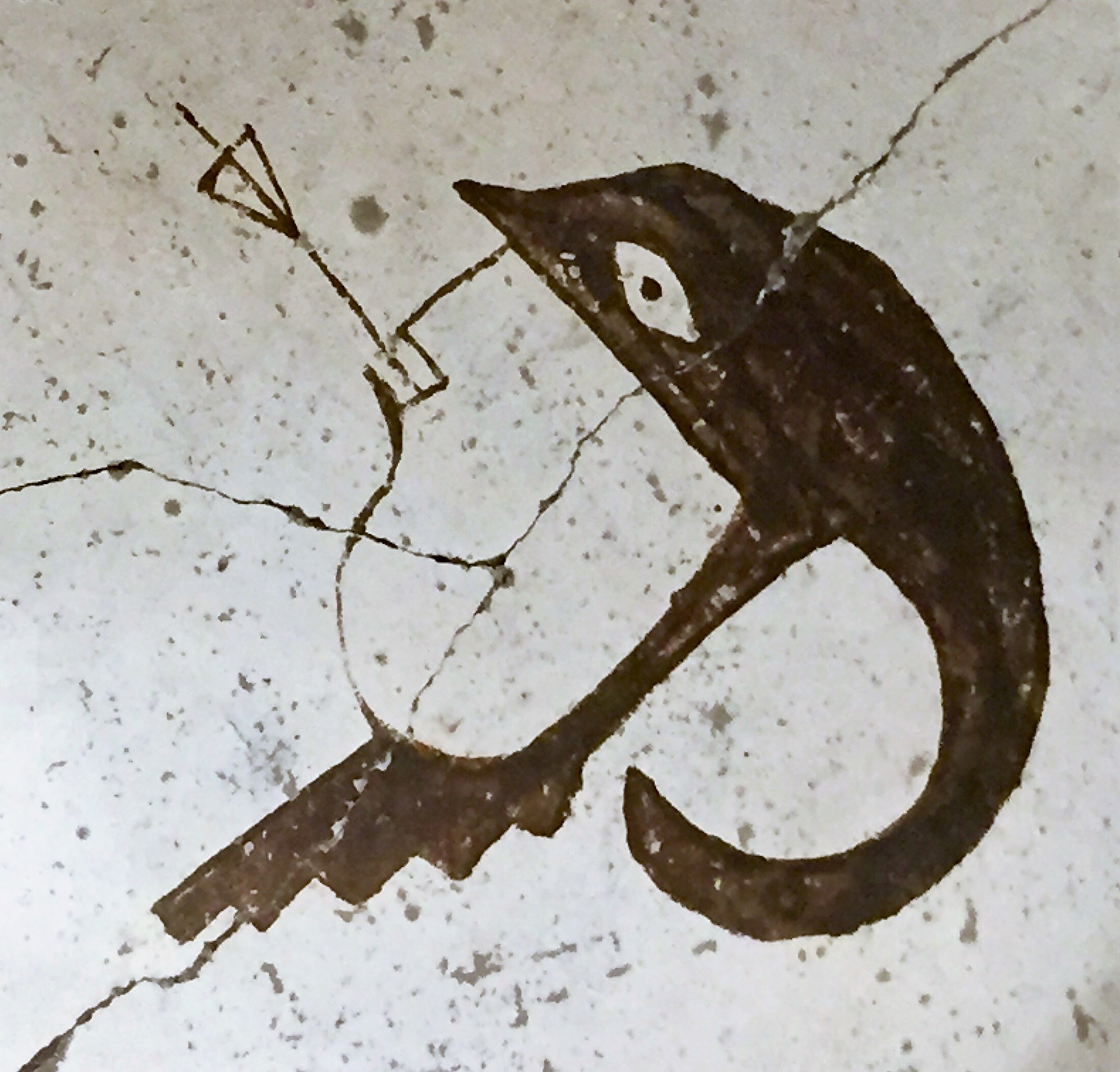

Classic Mimbres Polychrome bowl, Mogollon Mimbres, 1000–1150, ceramic, slip, and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift. 1988.115.FA

In honor of National Native American Heritage Month, take a closer look at the Mimbres bowls displayed in the DMA’s Native North American galleries on Level 4. I love how Mimbres artists balance color and form in a symmetrical framework, creating dynamic imagery. Geometric motifs, center-oriented designs, and figures add aesthetic interest, but may also function as symbolic clues to Mimbres cosmology and worldview.

The greater Mimbres region (shaded area) and contemporaneous culture areas, page XXII, Brody, J.J. Mimbres Painted Pottery, Rev. ed. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 2004.

Mimbres communities settled along the Mimbres and Gila River Valleys in southwestern New Mexico from around 200-1150 C.E. Throughout that time, Mimbres ceramic art underwent several transformations in style and form. Early corrugated wares had grooved, textured surfaces, while red-on-white painted wares eventually transitioned into the black-on-white or polychrome bowls of Classic Mimbres art. These Classic bowls were skillfully fashioned, from their delicately balanced form to their complexly painted designs.

Making a ceramic bowl required a methodical process of gathering and preparing clay. First, the artist removed undesired particles, soaked the clay in water, and kneaded it to remove air pockets. Next, the artist added temper, such as sand, to protect against shrinking or cracking. Attaching coil after coil, the artist created the bowl’s form, while flattening or scraping the sides to obtain a smooth surface. Finally, the artist decorated the interior with a fine, white slip and painted designs with an iron-based paint.

Under high-oxygen firing conditions, the iron in the paint turned a deep red-brown, but in low-oxygen environments, the iron fired gray-black. Many Classic Mimbres bowls have a true black-on-white design, but others show a blending of dark and light red. The color gradation suggests that Mimbres artists may have adjusted firing conditions to achieve visual effects with color.

-

-

Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: three pronghorn, Mogollon Mimbres, 1000–1150, ceramic, slip, and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift. 1991.348.FA

-

-

Detail, Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: three pronghorn, Mogollon Mimbres, 1000–1150, ceramic, slip, and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift. 1991.348.FA

Among the bowls on display at the DMA are three that feature and blend these styles, motifs, and images in distinct ways. In the Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: three pronghorn, we see how the Mimbres used rotational symmetry to transform a single image into three forms. Mimbres artists frequently created designs that draw the viewer’s eye to the center. In this bowl, the artist rotated three pronghorn antelope around the bowl’s center, which is marked with a triangle defined by empty space. Some scholars suggest a parallel between the way historic and contemporary Pueblo communities organize designs on ceramic vessels. The center-oriented design may refer to the ordering of the universe of divisions between worlds. In another impressive detail, the artist mirrored the spiral-diamond design on the pronghorn’s bodies with the decorative triangles along the bowl’s rim.

-

-

Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: bighorn sheep, Mogollon Mimbres, 1000–1130, ceramic, slip, and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift. 1990.215.FA

-

-

Detail, Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: bighorn sheep, Mogollon Mimbres, 1000–1130, ceramic, slip, and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift. 1990.215.FA

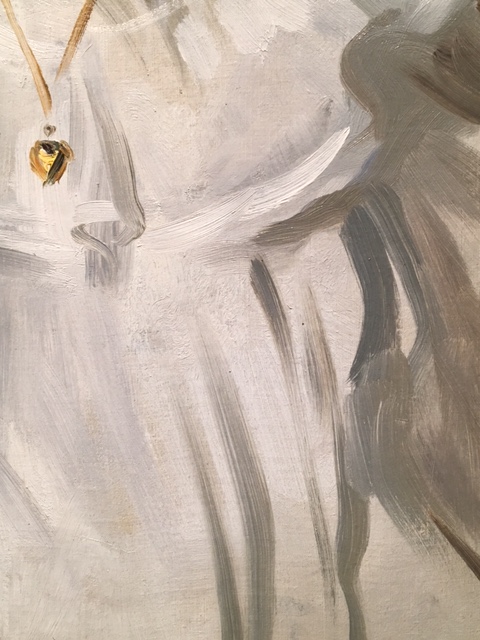

In the Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: bighorn sheep, we see a different form of Mimbres symmetry. This bowl shows reflectional and rotational symmetry, as the artist reflected the bighorn over a central horizontal line to face opposite directions. The reflected step motif at the bowl’s center may be the artist’s rendition of the bighorn’s mountain home. The trapezoidal designs that frame the bighorn on either side illustrate the artist’s ability to produce reflectional and rotational symmetry on a smaller scale. The motifs in this bowl are excellent examples of the geometric shapes, fine-line hachure, curved spaces, and framed bands that characterize Mimbres art.

-

-

Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: animals, head, and figure, Mogollon Mimbres, 1075–1130, ceramic, slip, and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift. 1990.219.FA

-

-

Detail, Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: animals, head, and figure, Mogollon Mimbres, 1075–1130, ceramic, slip, and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift. 1990.219.FA

Compared to the other two bowls, the Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl: animals, head, and figure has a more free-form style. Here, the artist applied a loose form of reflectional and rotational symmetry, so that each bighorn has a different geometric motif. The paint color, which transitions from red to black, may have special importance. For example, in several Pueblo communities, colors can convey spiritual meaning or be associated with the cardinal directions. As in the other bowls, the artist shows the bighorn, the anteater-like figure, and the small human head in profile. In contrast to the other two examples, the wide, white background places full emphasis on the four colorful figures rotated around the bowl’s center.

Mimbres art draws actively on a close relationship between people and nature. From working the clay to portraying animals that the Mimbres hunted, domesticated, or honored, these exceptional artists of the prehistoric Southwest allow us to envision how past peoples interpreted and interacted with the world.

Danielle Gilbert is the McDermott Graduate Intern for Arts of the Americas at the DMA.