While museums increasingly take on roles in entertainment and education, they remain, like libraries, stewards of knowledge. However, sometimes this knowledge—what we think of as researched, established fact—is misguided. Admitting you’ve been wrong can be humiliating, yet slip-ups within the museum field encourage humility. Mistakes remind us that correcting, preserving, and adding to the record is, at the end of the day, what museums are called to do.

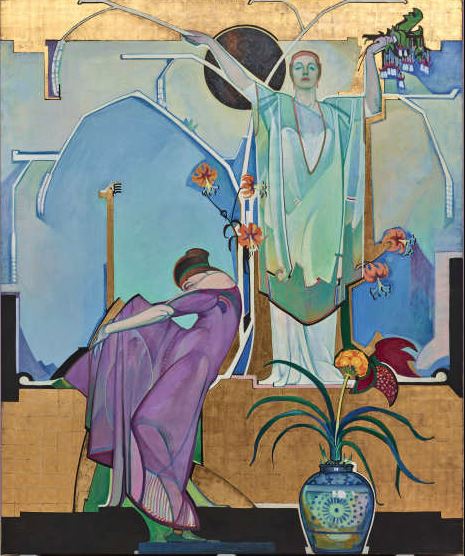

The blunder in question surrounds the identity of the objects seen in Gerald Murphy’s 1924 painting Razor.

Gerald Murphy, Razor, 1924, oil on canvas, The Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of the artist, © Estate of Honoria Murphy Donnelly, 1963.74.FA

The journey began when Sue Canterbury, The Pauline Gill Sullivan Associate Curator of American Art, received an email from a concerned fountain pen enthusiast who notified her that the Museum was misinformed about Murphy’s painting. Sue asked me to create a timeline of recorded references to find out when the misinformation began. Then I was asked to search for what may have misled our predecessors and to untangle this 15-plus-year hiccup in the DMA’s records.

For years, the Museum said the razor and pen featured in the painting were modeled after products designed or sold by the Murphy family through their successful storefront, Mark Cross & Co. While it is true that Murphy designed a prototype razor in the mid-1910s that had a short burst of fame from 1912 to 1913, and that his family’s company most likely sold top-of-the-line writing utensils in their luxury goods stores, the razor and pen are NOT Murphy-designed objects. After thorough research, I concluded that years of accidental conflation caused the mix up.

The Mark Cross logo after its inception in 1845. Gerald Murphy’s father, Patrick Murphy, bought the company in the 1880s, which led to the family’s increasing wealth. © Mark Cross Leathergoods LLC

Murphy confirms the object’s correct identity in his letters with former DMCA director Douglas MacAgy: “The first Gillette razor and the first Parker pen (of red rubber) were real objects (not gadgets) ‘no bigger than a man’s hand.’”

A letter from Gerald Murphy to Douglas MacAgy referencing Razor and Watch, another painting by Murphy, 1960, DMA Archives

The object for which Razor takes its name is a Gillette “New Standard” safety razor. This razor featured new technology that increased consumers’ ease of use and overall safety. Fewer shaving cuts? Yes, please! It was the most successful razor during the time of the painting’s creation and reached both American and European markets. By comparing the Mark Cross and Gillette razors below, and looking again at the painting, you can see how the Gillette attribution makes more sense with what Murphy illustrates.

A 1913 Mark Cross razor advertisement. Courtesy of jmudrick’s blog post on TheShaveDen.com. For more detail about the Mark Cross razor’s history, this is a great source!

A Gillette “New Standard” safety razor made sometime between 1920 and 1925. © Gillette.com. This image shows a gold version of the razor but it is structurally identical to the silver model seen in “Razor.”

The Parker Pen Company took the American (and later European) markets by storm with its iconic “Big Red” Duofold fountain pen in the early 1920s. Instead of wanting a new Xbox or iPhone as a gift, consumers hoped for a Parker pen.

Why? The pen featured cutting-edge technology, including a leak-proof inkwell system and a durable, strikingly modern red rubber shaft. Murphy’s detailing even alludes to it being not the first version of the pen but the glitzier 1923 version, which included the fashionable “gold girdle,” seen in the advertisement below.

Now to the probable sources of the mix-up: a combination of trying to make the painting more personal to Murphy, plus an unfortunate conflation of similarly named companies. Symbols are always intriguing and tempting for art historians. If Murphy had designed the razor and/or pen, it could be seen as a self-portrait; yet, Razor still can be, despite the objects not being of his design (see Deborah Rothschild’s book Making It New: The Art and Style of Sara and Gerald Murphy).

Additionally, an accidental conflation occurred between the Mark Cross name and the A.T. Cross Company, a popular producer of pens. A.T. Cross bought the Mark Cross company in 1983 (right before the first publication of the misinformation), as referenced on A.T. Cross’s website. Prior to the buyout, Mark Cross was known primarily for its leather goods, not its side hustle of writing accessories. Every source that labels Mark Cross as a pen company and the pen as sold/designed by Mark Cross occurs after this buyout date.

Murphy’s Razor and his dazzling 1925 painting Watch are currently not on view, but be sure to check them out in the DMA’s upcoming exhibition Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art, on view from September 16 through January 6!

Ashton Smyth is the Summer Curatorial Intern for American Art at the DMA.