What a year 2017 was at the DMA! Below is a brief look back on some of our memorable moments.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

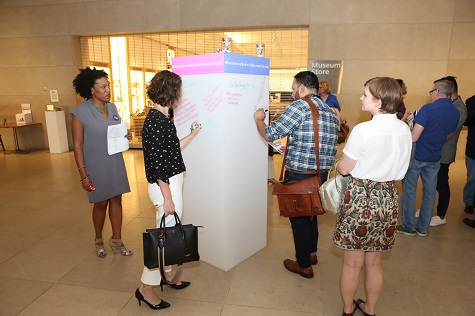

Photos of the January 2017 DMA Late Night. Images taken on Friday, January 20, 2017.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Photos of the April 2017 Late Night. Images taken on Friday, April 21, 2017.

-

-

-

Photos of the May 2017 “Mexico 1900-1950”-themed Late Night. Images taken on Friday, May 19, 2017.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Pano

-

-

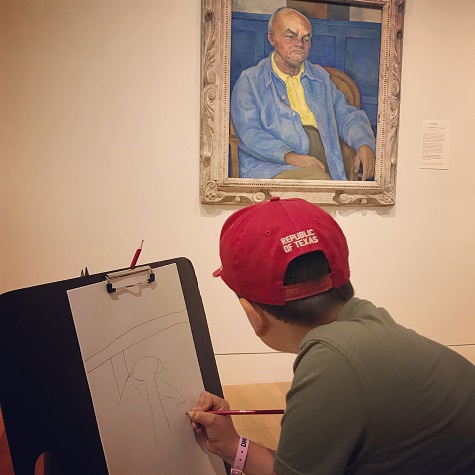

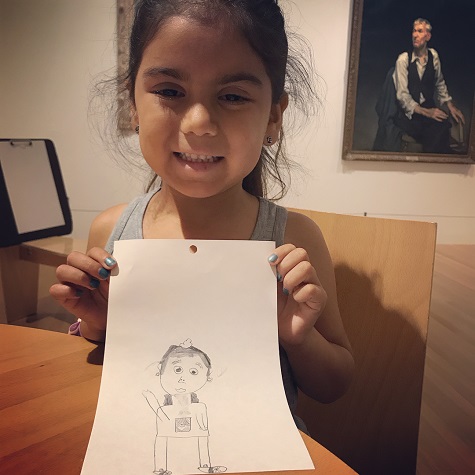

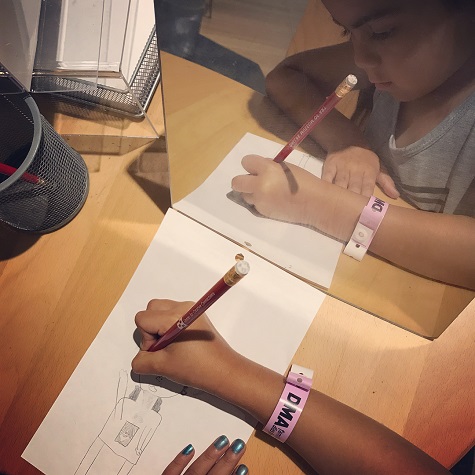

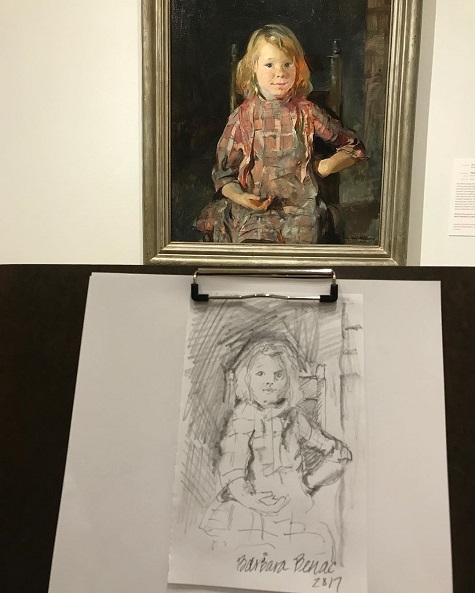

Photos of “Mexico: 1900-1950” during spring break. Images taken on Wednesday, March 14, 2017.

-

-

-

-

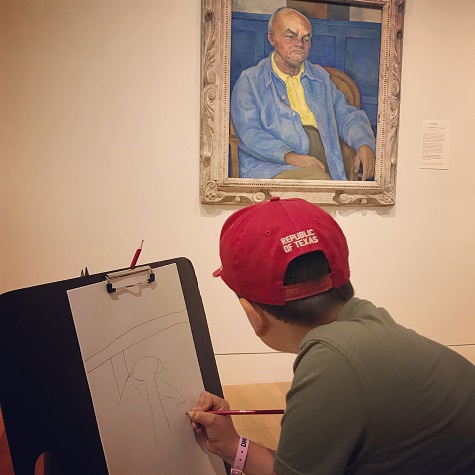

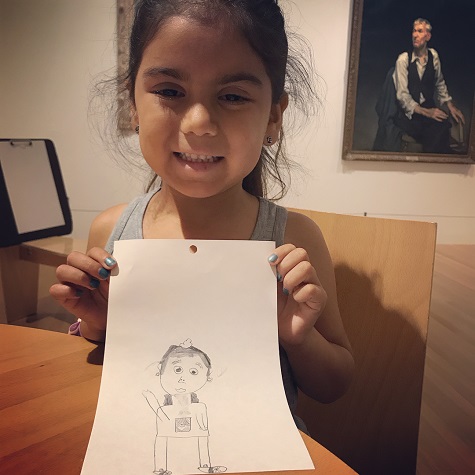

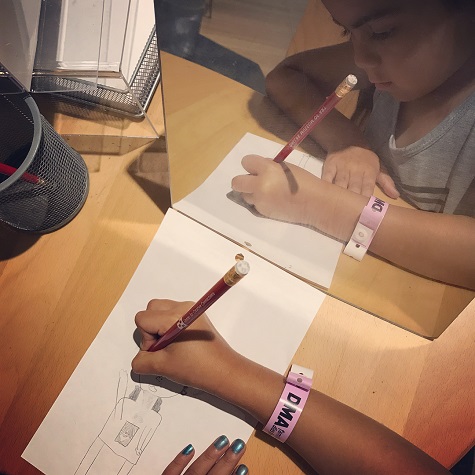

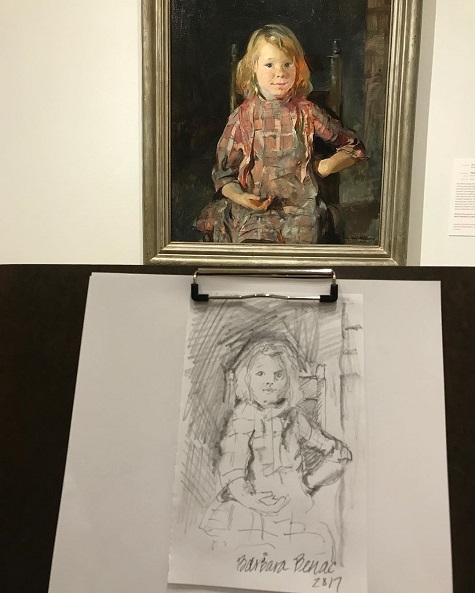

Photos from the August 2017 Late Night. Photos taken on Friday, August 18, 2017.

-

-

-

January

The launch of the C3 Visiting Artist Project.

The DMA Teen Advisory Council organized and debuted their Disconnect to Reconnect program.

The launch of Sensory Scouts, a monthly program designed for teens and tweens on the autism spectrum.

The 26th season of DMA Arts & Letters Live kicked off on January 14 with Zadie Smith.

The DMA welcomed Anna Katherine Brodbeck as The Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art.

February

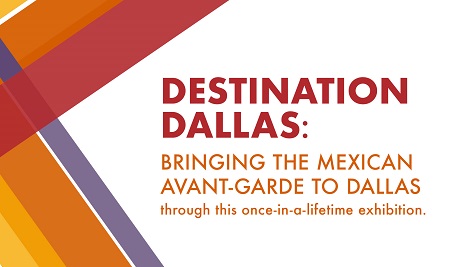

The DMA launches its first ever crowdfunding campaign, Destination Dallas: Bringing México 1900–1950: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, and the Avant-Garde to Dallas, bringing in more than $100,000.

The DMA’s Speakeasy was the bee’s knees, celebrating the Shaken, Stirred, Styled: The Art of the Cocktail exhibition.

March

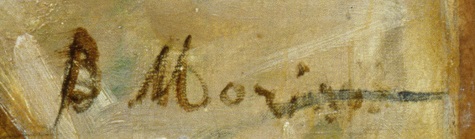

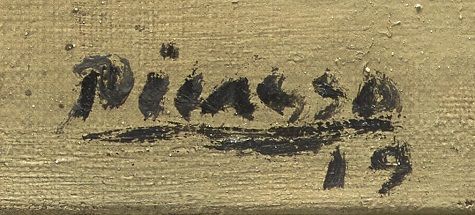

México 1900–1950: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, and the Avant-Garde opens at the DMA on March 12, presenting a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience the greats of Mexican modernism in Dallas.

The first of a total of 12 DMA Family Days launched on Sunday, March 26, with a total of 39,778 visitors on those days, with almost half being first-time visitors.

April

The 52nd Art Ball raises more than $1.3 million.

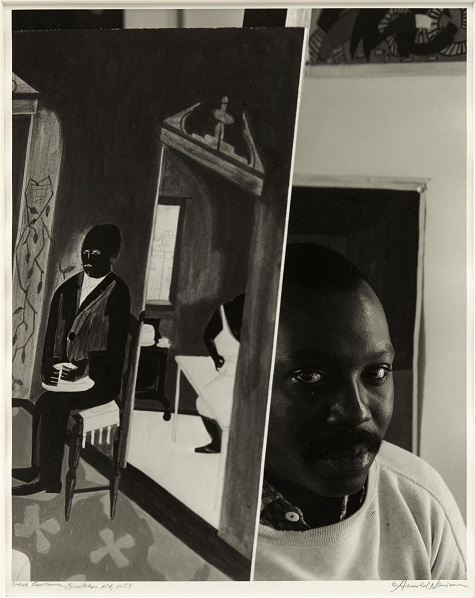

The DMA is proud to be the recipient of the second annual Dallas Art Fair Foundation Acquisition Program, which included the addition of work by Justin Adian, Katherine Bradford, Andrea Galvani, Matthews Wong, and Derek Fordjour.

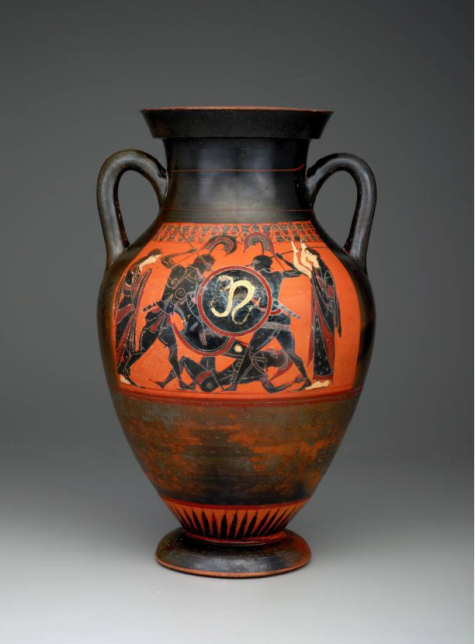

The Keir Collection of Islamic Art Gallery opens to the public, marking the largest public presentation of the collection to date.

May

Aruto’s Nest got a new look.

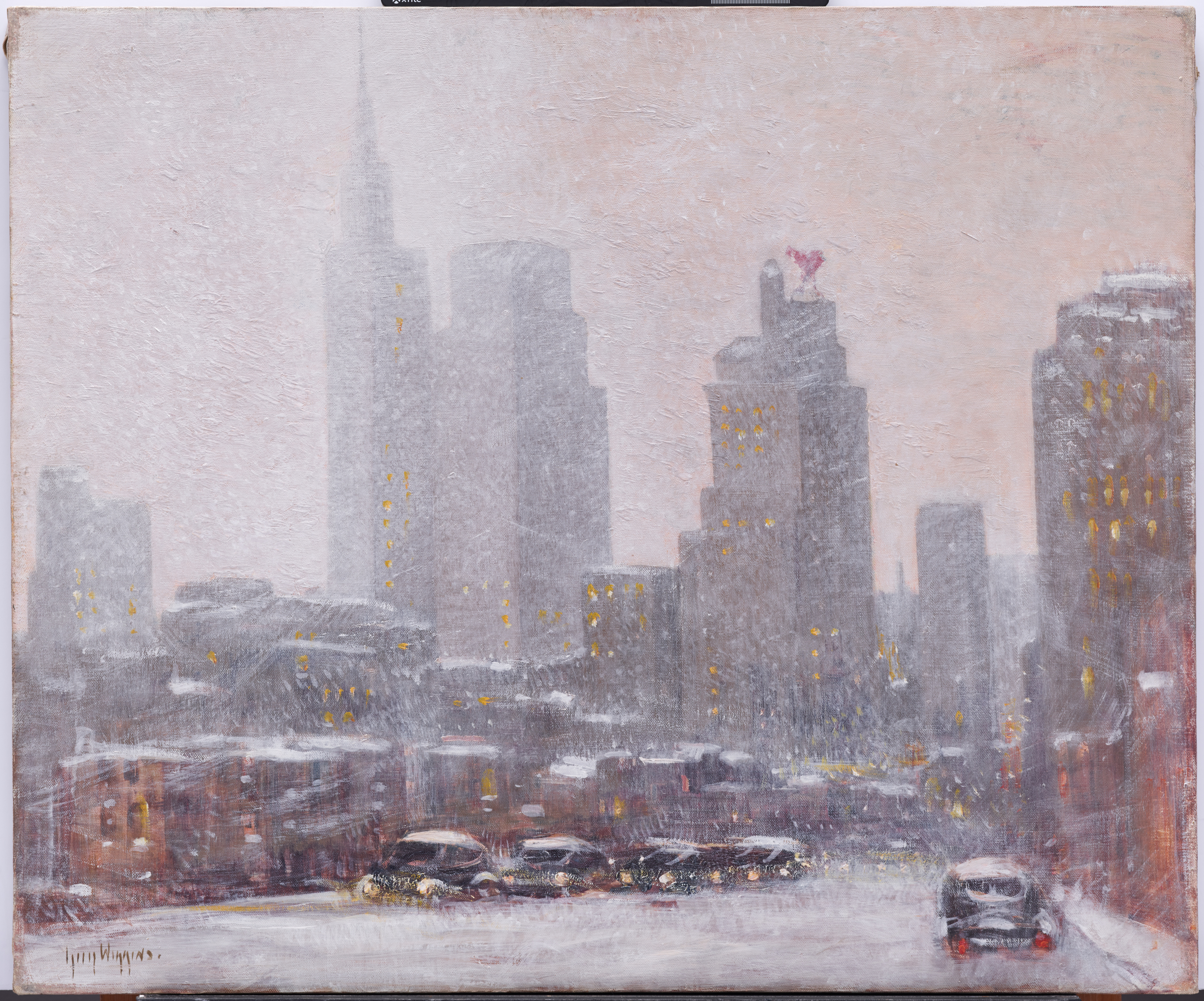

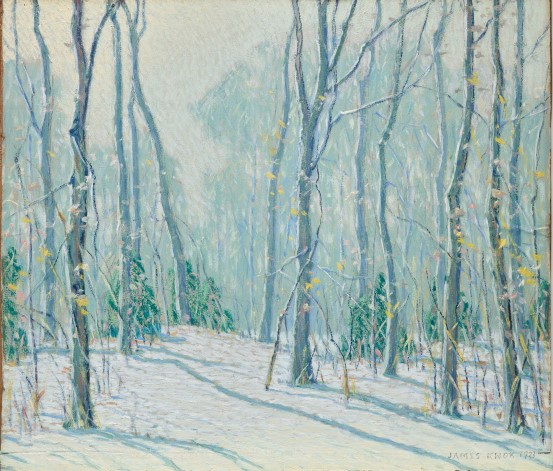

Visions of America: Three Centuries of Prints from the National Gallery of Art and Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion open, kicking off our summer fun.

June

Works of art centered around the idea of communication went on view in C3.

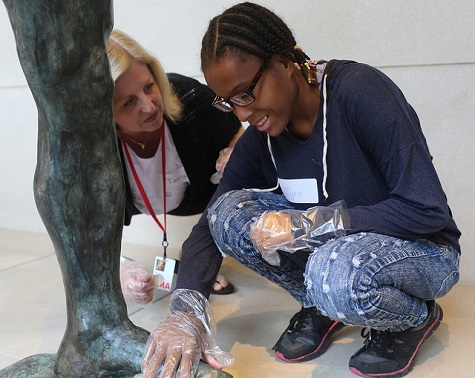

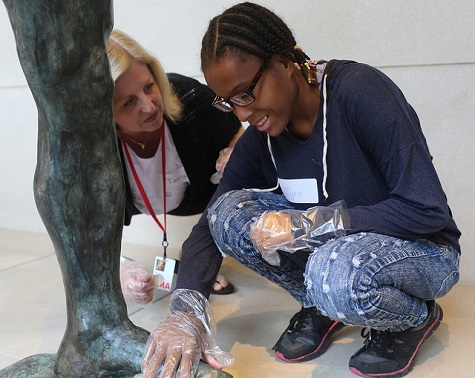

Twenty-four DISD students with vision impairment participated in the DMA’s first indoor touch tour of the Museum’s European sculptures.

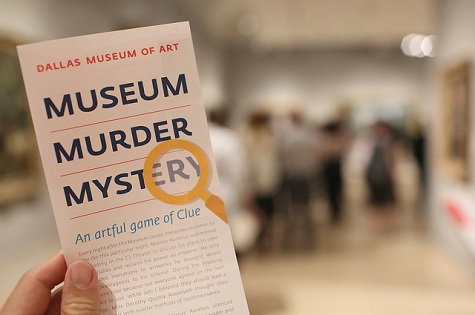

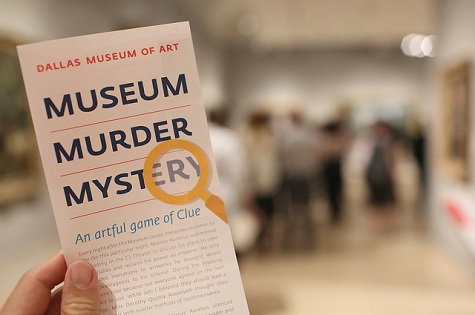

Six hundred and fifty sleuths help solve our sixth annual Museum Murder Mystery evening.

President and Mrs. Bush explored México 1900–1950 with DMA Director Agustín Arteaga.

July

More than 1,000 people participated in our Guinness World Record attempt on what would have been Frida Kahlo’s 110th birthday during the DMA’s Frida Fest, with almost 6,000 visitors in attendance.

México 1900–1950 welcomed 125,894 visitors before it closed on July 16.

Visitors went gaga for our Iris van Herpen-themed Late Night featuring a Lady Gaga costume contest.

August

Guerrilla Girl Käthe Kollwitz discussed the groups iconic work during the August Late Night

The Junior Associates celebrated the last days of summer during their August 25 Kickoff Party.

September

The DMA celebrated the first anniversary of Agustín Arteaga’s tenure as The Eugene McDermott Director.

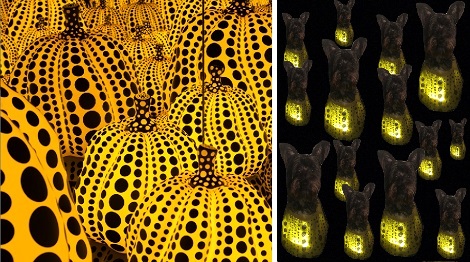

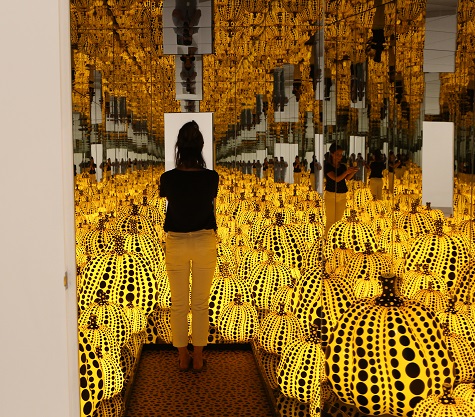

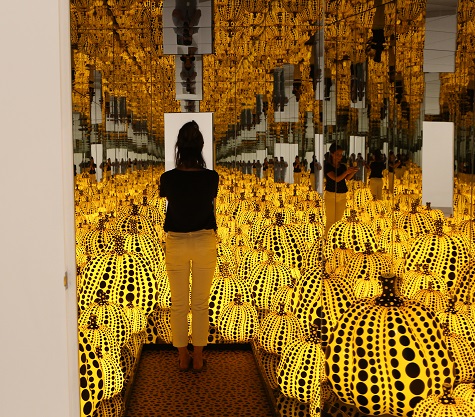

DMA Members got to be the first to step into infinity during two weeks of preview days for Yayoi Kusama: All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins.

More than $17,000 was gifted to the DMA during North Texas Giving Day.

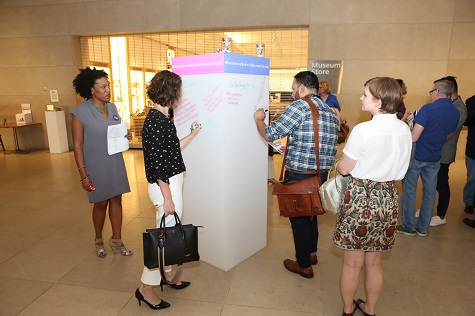

The Dallas Cultural Plan held a kickoff event at the DMA to help shape the future of arts and culture in Dallas.

October

Yayoi Kusama officially opened and immediately became an Instagram sensation.

Truth: 24 frames per second, the DMA’s first time-based media exhibition, opened.

TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art, benefiting amfAR and the Dallas Museum of Art, raised over $7.3 million.

It was Potter-mania during a spellbinding Second Thursday with a Twist.

November

The second annual Rosenberg Fête featured an evening themed around François Lemoyne’s The Bather from the Rosenberg Collection.

More than 7,000 visitors took part in our three-day Islamic Art Festival: The Language of Exchange celebrating the Keir Collection of Islamic Art.

December

Asian Textiles: Art and Trade Along the Silk Road goes on view in the Museum’s Level 3 gallery.

We traveled to a gallery far, far away during the final Second Thursday with a Twist inspired by Star Wars.

The DMA reflects upon a year of amazing art, events, and visitors!