There must be something in the water, LITERALLY, since many of the most recognized artists of the 19th and 20th century are born under the sign of the Scorpio–whose zodiac element also happens to be water! The birthdays of Pablo Picasso, Claude Monet, Roy Lichtenstein, and Georgia O’Keefe, just to name a few, all fall between October 24 and November 23. So what is it exactly that makes these Scorpios so artistically inclined?

Scorpios are considered one of the most fierce and determined zodiac symbols. Their strength and independence commands attention and they are known to possess the ability to manipulate and hypnotize. The intensity of the Scorpio spirit is often misunderstood as insincerity, but beneath their cool exterior their emotional side runs deep. In relationships, Scorpios set high expectations of themselves and expect the same commitment in return. This loyalty and passion carries into all aspects of their lives and, at times, their desire for perfection can make them obsessive, demanding, and obstinate. While these characteristics might deter others, Scorpio’s thrive on a challenge and will see a task through no matter the obstacles–often to great success. Scorpio’s live life to the extreme and banality is never an option!

Using this description as a guide, it is no wonder that these savvy Scorpios developed and practiced a style all their own! Backed by their passion and determination, they explored new mediums, scientific developments, styles of representation, and ideas.

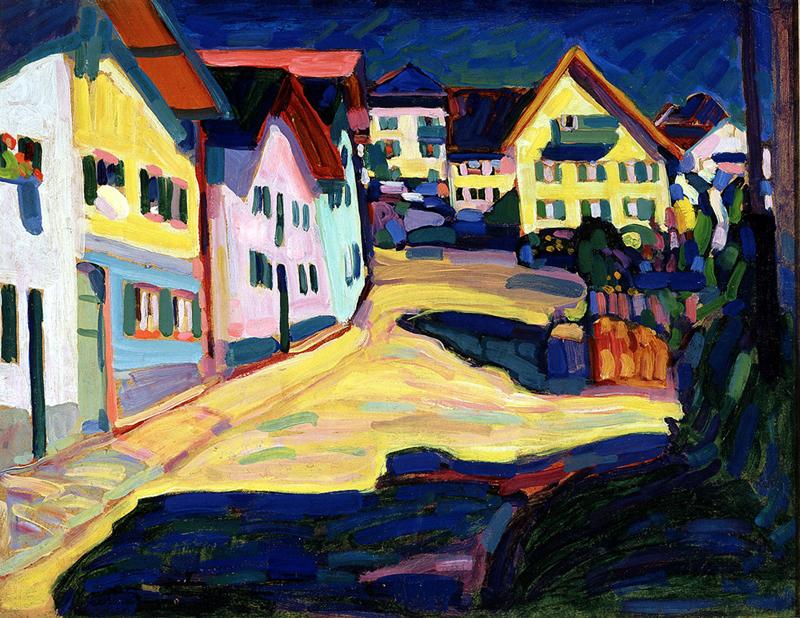

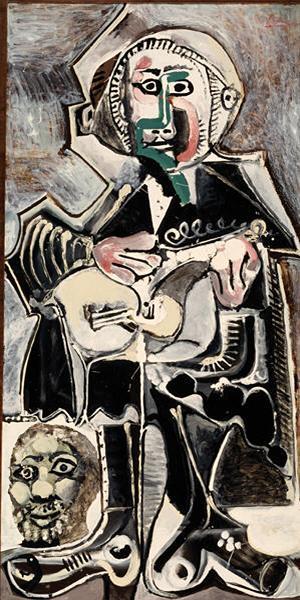

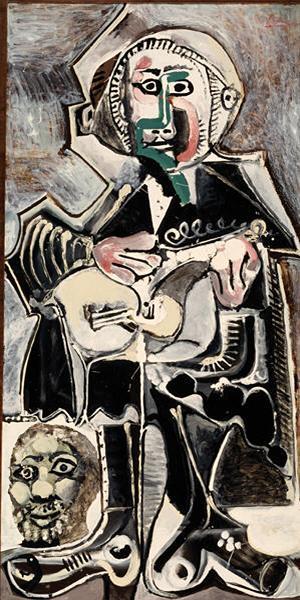

Pablo Picasso – October 25

Because of Pablo Picasso’s innovations and contributions to the history of art, he has become one of the most recognizable artists in the world. This status is not unjustified as his work truly defined an era, changing art and artistry forever. Together, Picasso and Georges Braque developed Cubism, a style that radically re-structured the practice of painting. In both his life and his work, Picasso exhibited many of the signature traits of a Scorpio: he was intellectually rigorous, indulgent (both personally and artistically), and often obsessive. Later in life, this obsession manifested into a superstition in which he believed he could prolong death through artistic production. The all-knowing eyes of The Guitarist, above, also has connotations with Scorpio astrology. Eyes are a Scorpio’s most powerful physical trait and have been said to have the ability to hypnotize. This characteristic was not missed by Picasso, whose friend stated that he observed “the eyes of the canvases, by the way they had of staring into ours from deep inside those painted heads…never ceased asking us questions…We would look at the canvases straight in the eyes.”

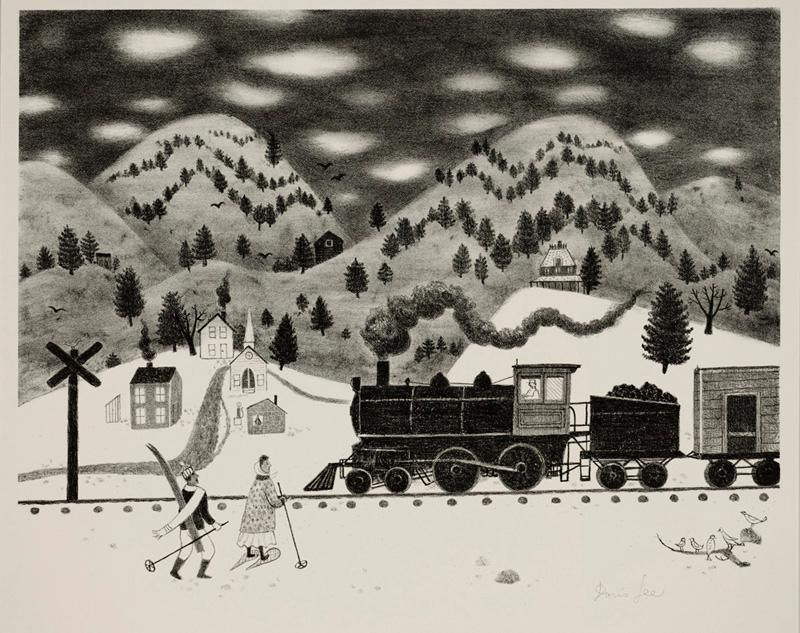

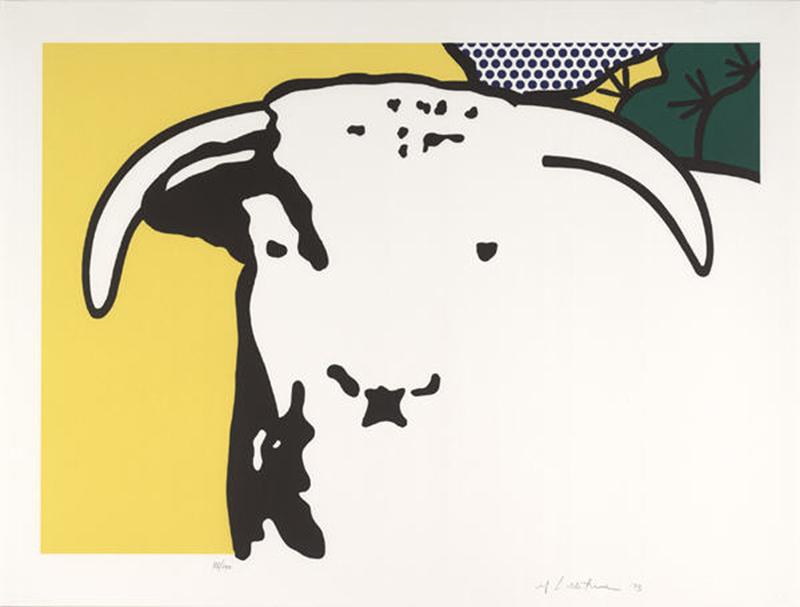

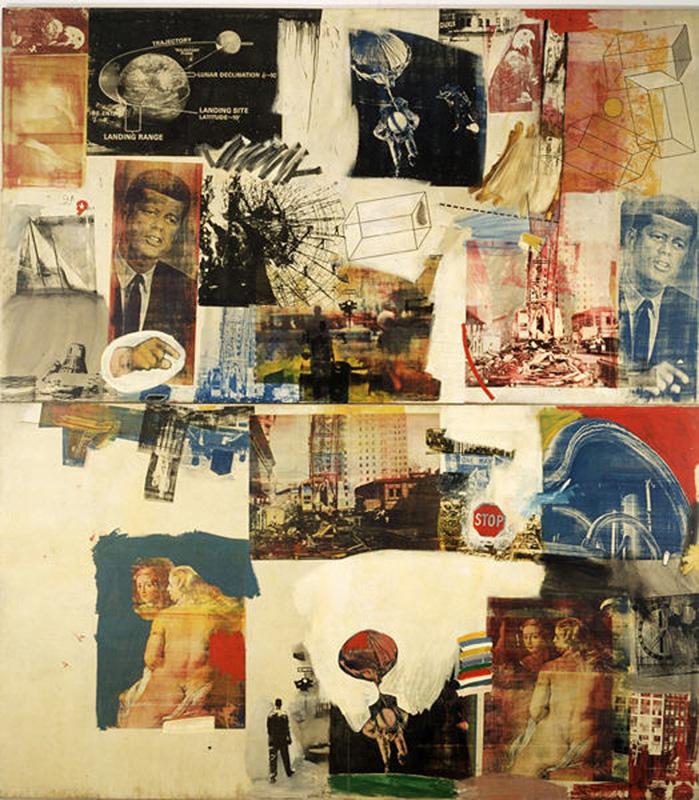

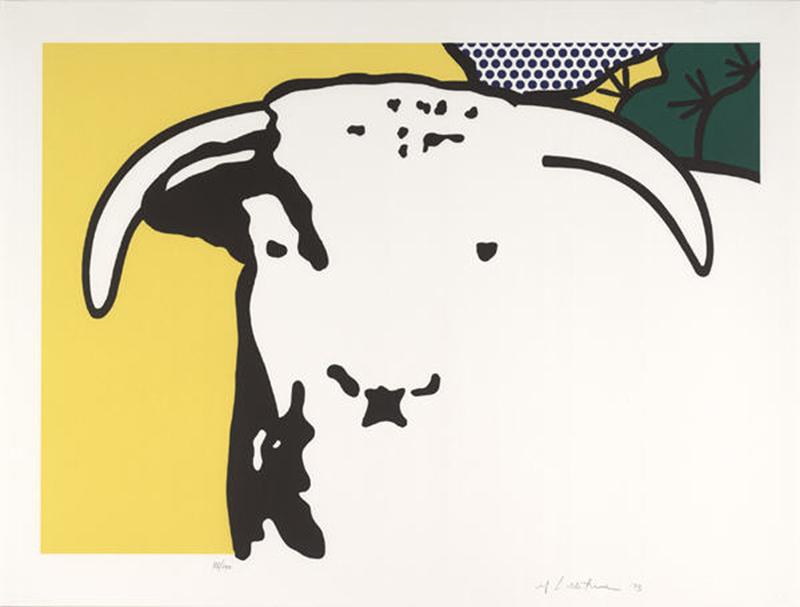

Roy Lichtenstein – October 27

Roy Lichtenstein’s Bull Heads series directly challenges and satirizes the art historical practice of Cubism. The emblem of Pablo Picasso’s Spanish roots–the bull–becomes increasingly unrecognizable as the prints progress into further simplified geometric shapes. Lichtenstein frequently consulted art historical tradition to inform and direct his works. He is largely recognized for his appropriation of the style and content of comic strips, a focus that again derived from his interest in how subject matter is not only depicted, but digested. This acuity reveals Lichtenstein’s interest in the past as a vehicle to explore new ideas and concepts.

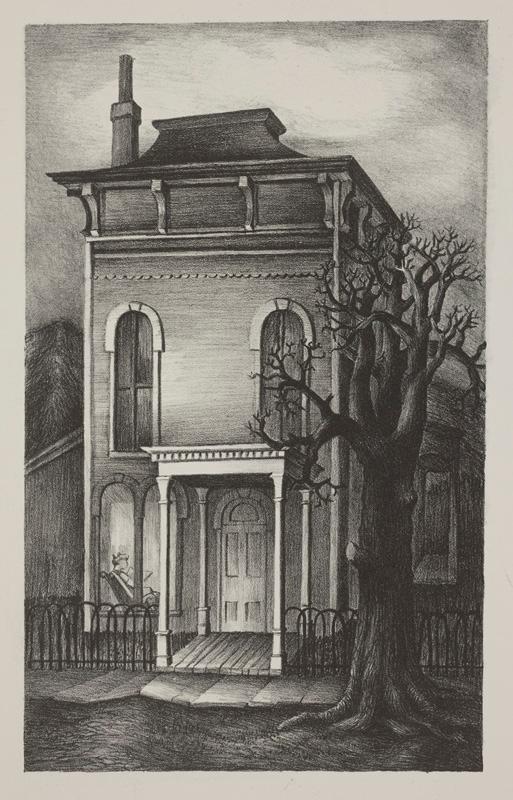

Auguste Rodin – November 12

Rodin realized his passion for art at a young age, and his talent was highly regarded during his adolescent years. He faced a humiliating defeat, however, when he was declined admission to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts three consecutive times. In order to make a living, Rodin worked for 20 years as a craftsmen and ornamenter. Throughout this time, he remained determined to further develop his passions and talents, attending classes, shadowing artists, and renting small studios in order to produce large figures. Now hailed for the materiality and dignity of his works, Rodin’s Scorpio characteristics of self-determination, willfulness, and originality pushed him to overcome obstacles and become one of the most recognizable and popular sculptors of the modern era.

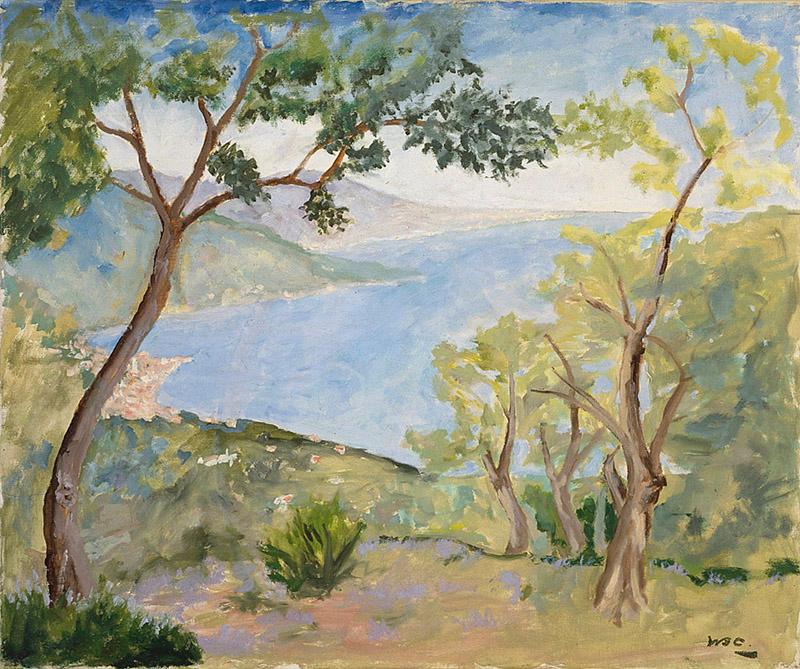

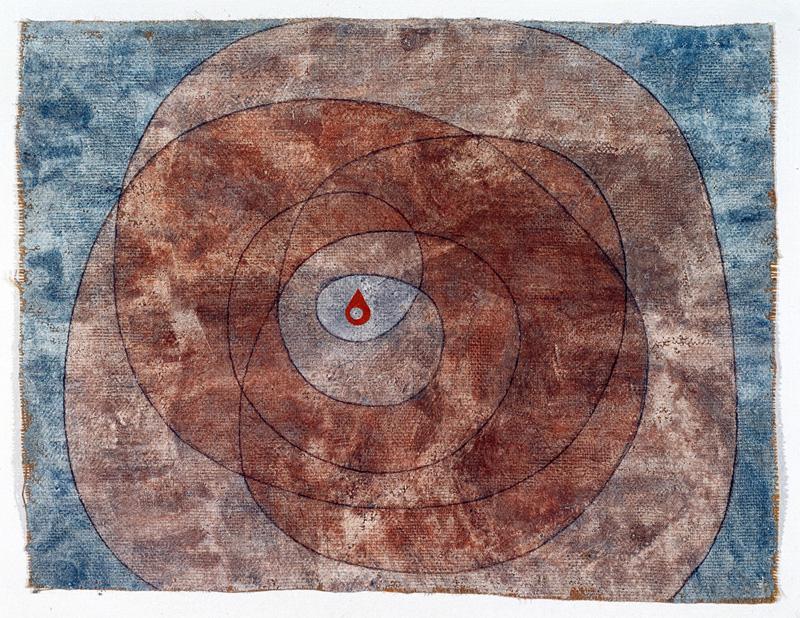

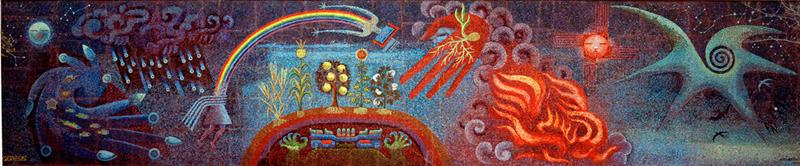

Georgia O’Keeffe – November 15

Georgia O’Keeffe is not only hailed for her work as an artist but also for her feminist and self-reliant character. O’Keeffe unapologetically pursued her artwork and her life as she pleased. She is quoted to have said, “I have but one desire as a painter: that is to paint what I see, as I see it, in my own way, without regard for the desires or taste of the professional dealer or the professional collector.” O’Keeffe’s vision is evidenced in her abstracted, yet acutely attentive representations of singular elements, such as her iconic paintings of flowers and desert-bleached skulls. She depicted her unique worldview in paintings of both natural and urban landscapes.

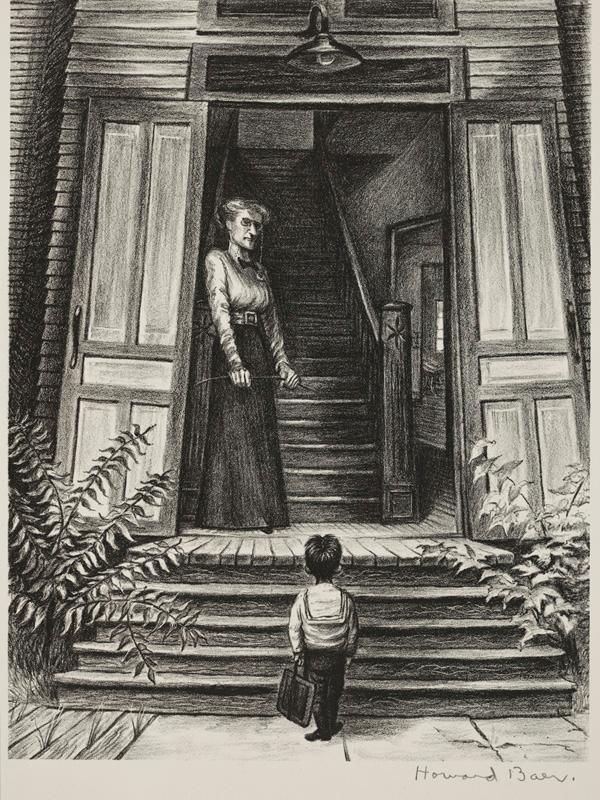

Jim Hodges – November 19

The work of Jim Hodges exemplifies the passion and loyalty of the Scorpio spirit. Our current exhibition, Jim Hodges: Give More Than You Take, speaks to Hodges’ commitment and generosity as an artist, a friend, a son, and a partner. Most of the works in the exhibition make direct or indirect reference to his interactions with loved ones, including Here’s where we will stay. This piece alludes to Jim’s mother and great-grandmother, who taught him how to sew and cultivated his understanding and patience for craft arts. Jim sewed each of the scarves together by hand, purposefully elongating the experience to allow time for meditation and reflection.

For more splendid Scorpios, check out the work of Johannes Vermeer (October 31), Robert Mapplethorpe (November 4), Paul Signac (November 11), Claude Monet (November 14), and Rene Magritte (November 22)! And don’t forget to tune in next month for some of our favorite Sagittarius artists!

Artworks Shown:

- Pablo Picasso, The Guitarist, 1965, Dallas Museum of Art, The Art Museum League Fund

- Roy Lichtenstein, Bull Heads I, 1973, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The 500, Inc.

- Roy Lichtenstein, Bull Heads III, 1973, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The 500, Inc.

- Auguste Rodin, The Shade, or Adam from “The Gates of Hell”, 1880, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene McDermott

- Georgia O’Keeffe, Grey Blue & Black—Pink Circle, 1929, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation

- Jim Hodges, Here’s where we will stay, 1995

Hayley Prihoda

McDermott Intern for Gallery and Community Teaching