In anticipation of the airing of the sixth season of Game of Thrones, we asked the DMA’s “Mother of Dragons,” curator Anne Bromberg, to share the history of dragons and the many ways they are represented in the Museum’s collection.

People all over the world have imagined dragons—horned, winged, and fire-spitting serpents—as powerful spirit figures, capable of both helping humans and killing them. Since actual snakes shed their old skins and appear to be newborn periodically, dragons were thought to be deathless. They were also usually considered to be both male and female in one body and thus were spirits of fertility.

Dragon eyes were thought to be translucent jewels, as they reflected the light of the moon and stars. Often these eyes were called pearls. As part of the natural forces in the world, dragons were associated with both earth and water; hence they represented the four basic elements: earth, air, fire, and water.

Stories about dragons appear in some of the earliest religious texts, both in Near Eastern kingdoms and early Greece and in the Hindu Upanishads. The Greeks called dragons Ouranos, the Heavens, who is both child and husband of Gaea, the Earth Mother. A form of dragon is notable in pre-Columbian religions as the feathered serpent, and in China and Japan as an imperial symbol. In India the dragon figure became the seven-headed cobra Naga king, while gods like Vishnu are associated with sacred serpents. Famous stories related to dragons include the Greek hero Perseus saving Andromeda from a sea monster and, in Christianity, St. George killing an evil dragon.

An interesting note on dragons is that early mankind, who imagined winged serpents, considerably anticipated modern science, which describes how birds descended from dinosaurs. The word dinosaur means “terrible reptile.”

Vase, Japan, n.d., gold lacquer, silver, and gold foil, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, The John R. Young Collection, gift of M. Frances and John R. Young, 1993.86.41.FA

Several vases in the DMA’s Young Collection of Meiji period decorative arts represent dragons as part of the design. Although most of the Young Collection works were made for the export market to Europe or America, the nature of these dragons is derived from Chinese art. On the neck of this handsome vase, the main scene of which shows a typically Japanese landscape scene, a sinuous dragon curves around, as if waiting to ambush its victims. The silver dragon is the classical curving winged figure, with gaping jaws and large claws.

Takenouchi no Sukune Meets the Dragon King of the Sea, Sanseisha Company, designer, Meiji period, 1879–1881, bronze and glass, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, The John R. Young Collection, gift of M. Frances and John R. Young, 1993.86.11.FA

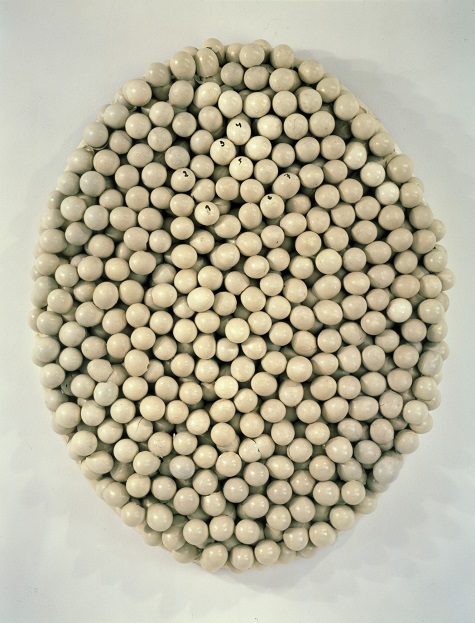

Takenouchi no Sukune Meets the Dragon King of the Sea is the most striking work in the Young Collection of Meiji period Japanese arts. These works were made for export to Europe and America and were deliberately made in styles that would appeal to the market for Japanese work. Here the Japanese warrior hero Takenouchi no Sukune is being rewarded by the Dragon King of the Sea, whom he has helped. An emissary of the king, accompanied by an attendant who appears as part human-part sea monster, offers the Jewel of the Tides to the warrior. It resembles a pearl, recalling that dragon eyes were imagined as jewels or pearls.

The base of the work is like a sea shore, with a rocky strand covered with crabs, snails, and terrapins. The under support is raised on sea dragon feet. The artist has brilliantly imagined a folk tale as a grand dramatic scene.

Dragon finial, Thailand, 15th–17th century, bronze, Intended bequest of David T. Owsley, PG.2007.57

In Southeast Asia, where kings in Cambodia and Thailand often identified themselves with Hindu or Buddhist deities, dragons were considered beneficent beings, powerful, but protective of the king and his people. Upper-class palanquins (carrying chairs) were ornamented with various auspicious images, including dragons. This example is a fine piece of craftsmanship that suggests the nature of dragons as beautiful, sinuous figures, with the fierce jaws of a killer but also the grace of a winged serpent. The Hindu Naga serpent-king is adapted to the finely detailed bronze work of the Thai kingdoms.

Finial: dragon head, Iran, Seljuk period, 11th–14th century, bronze, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1963.24

This ferocious looking dragon head from Iran is another example of using popular spirit imagery to ornament furniture and other useful objects. The dragon’s jaw gapes wide, showing sharp teeth and suggesting the fire that dragons were believed to spit. Religious imagery in ancient civilizations was as much about nature as mankind, since people were very dependent on the natural world for food, clothing, and building materials. The early Persians, as well as the Greeks and many peoples, projected their fears and hopes onto spirits that, like dragons, embody the power and violence of nature, as well as showing protective qualities.

Shiva Nataraja, India, Chola dynasty, 11th century, bronze, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Eugene McDermott, the Hamon Charitable Foundation, and an anonymous donor in honor of David T. Owsley, with additional funding from The Cecil and Ida Green Foundation and the Cecil and Ida Green Acquisition Fund, 2000.377

The great god Shiva was associated with serpent dragons, as you see in this great sculpture, where the god wears snake bracelets; however, Shiva is far more closely related to dragons than his ornaments indicate. In his cosmic form as Nataraja, the divine dancer, Shiva is encircled with flames. As the lord of life, death, and rebirth, he symbolizes creation, destruction, and ongoing life, as dragons were thought to do. In many ways, Lord Shiva was himself a dragon. The circle of flames surrounding him and the fire he holds in his hand represent death and the burial ground, but also pulse with continuing life. Like dragons, Shiva is a god of fertility. His hair is the eternal waters of Mother Ganges. The drum he carries holds the music of life. Again like dragons, he can bring both disaster and new birth.

Blue five-clawed dragon robe, China, late 19th century, China, silk and metal-wrapped yarn, Dallas Museum of Art, anonymous gift in honor of Joe B. Blakey, 1981.6

As symbols of prosperity and power, dragons in China became particularly associated with the Chinese emperor and his relatives and associates. This fine silk and metallic robe is one of several garments at the DMA that exemplify such Chinese taste. The dragons here are particularly charming and attractive, as they curl around, rather like superior pets. Another Chinese belief was that dragons could shrink themselves to the size of silk worms or blow themselves to the size of a thunderstorm. As in other cultures, Chinese dragons represented the four elements of earth, air, fire, and water.

Albrecht Dürer, St. George on Foot, c. 1502-c. 1503, engraving, Dallas Museum of Art, bequest of Calvin J. Holmes, 1971.83

German artist Albrecht Dürer’s image of St. George shows the hero as he has just slain an evil dragon. European Christians believed in the monstrous character of dragons, unlike the favorable idea you find in Greece, India, or China; however, in another way St. George is the successor of a Greek hero like Perseus, who also killed vicious dragons. In Christianity, a dragon was seen as an aspect of satan. In Dürer’s powerful scene, St. George seems to have effortlessly crushed the fallen dragon.

Figure of a chimera (mythical beast), China, 25–220 C.E., earthenware and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, anonymous gift, 1995.66

An imaginary animal closely related to dragons is the chimera, a vision that first appeared in central Asia, but was to become popular from Europe to China, thanks to trade along the Silk Road. The chimera combines lion, goat, and snake features. Like dragons, it spits unquenchable fire, and can destroy people or bring them good fortune. In China it became, like dragons, an image of prosperity and power.

Buddha Muchalinda, Cambodia, Khmer empire, late 12th–early 13th century, copper alloy, Dallas Museum of Art, the Cecil and Ida Green Acquisition Fund, 2005.3.a-c

In this fine Cambodian image, the Buddha is shown meditating before he achieved enlightenment. According to a story of this time in the Buddha’s life, a demon of ignorance tried to prevent him from reaching the Dharma by raising the waters of the lake where he sat until they drowned him. But the Buddha-to-be was protected by the holy Naga serpent king, who lifted the Buddha up and saved his life. This image of the Buddha protected by the Naga serpent (as a seven-headed cobra) was to become one of the most popular Buddhist icons.

Helmet mask (komo), Mali and Cote d’Ivoire, mid-20th century, wood, glass, animal horns, fiber, and mirrors, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of David T. Owsley, 1997.24

Masks like this were used among the Senufo and the neighboring Bamana people by high-ranking members of the men’s powerful Komo association, which was responsible for maintaining social, spiritual, and economic harmony. The added female figure may refer to Senufo women as diviners. The fearsome image, with its sharp teeth and jutting animal horns and tusks, projects terror. Glass eyes and reflective mirrors add a sense of supernatural force.

Dr. Anne R. Bromberg is The Cecil and Ida Green Curator of Ancient and Asian Art at the DMA.