Our homes have taken on new significance in these past few weeks. We are getting to know much more intimately our rooms, our furniture, and certainly our roommates. We might be noticing the dust more on the floors, or the cracks in the ceiling. We might be noting habits that perhaps were always there, but have come to the fore.

Is there a chair you prefer to sit in for comfort? A window you often find yourself daydreaming out of? Is there a favorite sweatshirt or blanket you reach for when you feel a draft?

There might be things we are lacking, things that had broken that we had been meaning to replace. We might be farther away from the homes in which we were raised, and the families inside, and it might feel harder to get to those places.

Maybe that family heirloom is being revisited more often now. Hands grazing over the nooks and crannies in the wood. Smells from recipes handed down from generations might be flooding our kitchens, if we are lucky.

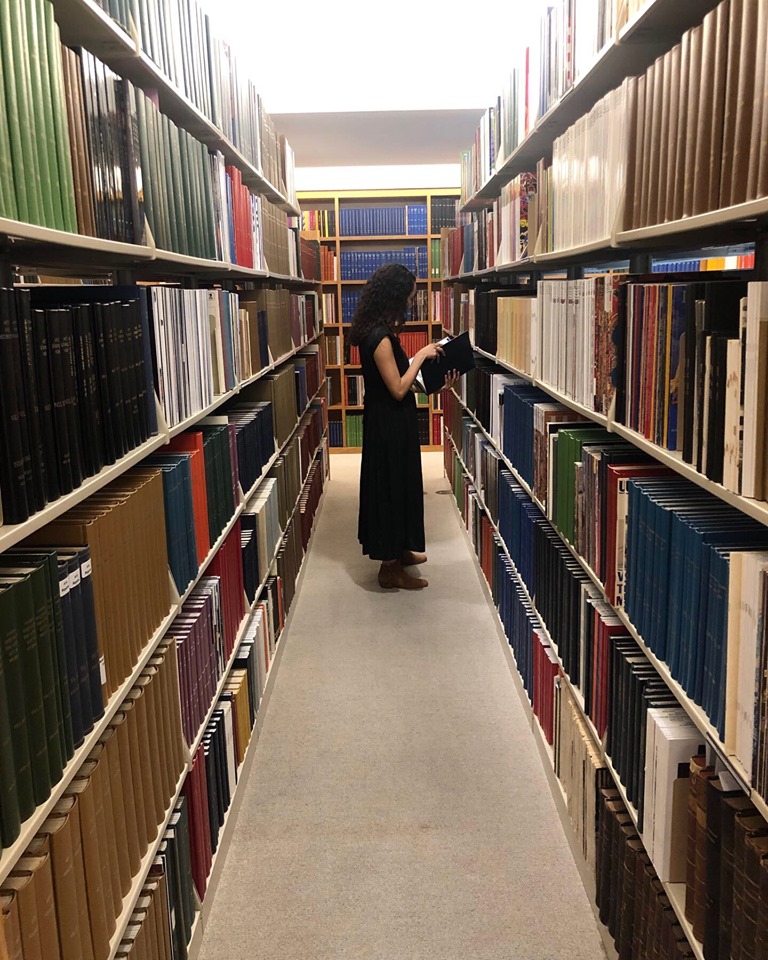

Our homes are microcosms of ourselves. They are our habits embodied. They are visualizations of our personalities. They can make us feel safe, but they can also scare us. The storms in the middle of the night might cause strange sounds and shadows to appear. The house can take on a life of its own. But it’s ultimately a shelter, and a home is a privilege not everyone has.

A house is also a boundary between ourselves and the world around us. We might see neighbors pass by our windows for the first time. We might peer into brand new rooms, far away, via technological devices, now that our schools and businesses are being conducted from home.

The exhibition For a Dreamer of Houses was organized before we as curators had any idea how much time we would all be spending in our own homes. Indeed, currently you can see the show via the comfort of your pajamas in 3-D on the web. But it was born from ideas circulated in philosophy, psychology, and sociology in the last hundred years. Hilde Nelson, Chloë Courtney, and I developed the concept for the show over the past year, inspired by recent acquisitions of immersive installations that brought to the fore just how wonderful the home is. Not just as a well-known and -loved domestic space, but as a place of fantasy.

We noticed that artists’ depictions of the home were reflecting our increasingly globalized world, re-creating a childhood house that could fit inside a suitcase. Or sociopolitical issues, like state-sponsored violence, imagining how furniture could reflect invented futures that were nurturing instead of traumatizing. Then, a global pandemic arose, and we were startled to realize how works in the show, chosen months ago, seemed to presage a strange new reality, with quarantining procedures, new emphasis on hygiene, and the fear of illness striking our loved ones.

But in spite of these fears, readers, we saw a resiliency in the worlds depicted by these artists. We still see a bright future, where we can take the lessons learned in the imaginative worlds of art, and apply them to a reality where we are all in this together, helping build a more equitable and safer future. And so we look to art, just like to the home, to visualize our shared humanity. And we have lots more time to look, and reflect on what we are seeing, at home.

Dr. Anna Katherine Brodbeck is the Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art at the DMA.