On Tuesday, December 11, archaeologist and food writer Farrell Monaco will be here for a talk and feast exploring ancient Roman cuisine. Monaco is the author of a celebrated food blog, Tavola Mediterranea, in which she explores recipes from across the Mediterranean and even re-creates recipes from the archaeological record.

In what has become a tradition for the Adult Programs team whenever we have a program about food, we tried our hand at making a few of the recipes featured in Tavola Mediterranea. You can find our other cooking attempts here, here, here, and here.

Katie Cooke, Manager of Adult Programs

When scrolling through the blog, the Libum caught my eye. I think because of a distant memory about the sweet bread that the Romans ate, from my days learning Latin. I also thought that the idea of an ancient cheesecake drizzled with honey couldn’t be that bad, even with my amateur baking skills.

The ingredients list could not have been easier to assemble. The base for the bread was only three things: eggs, flour, and ricotta. I had Great British Bake Off in the background, so I was reminded to let it proof and not knead it into a stiff mass.

While the dough was resting, I arranged the bay leaves on the bottom of the pans so that the bread would sit on them and soak up all the delicious, savory flavor.

I split the dough between two pans as the recipe says, and it’s a good thing Farrell specified that, because the baking time is already an hour—I would’ve been up very late if all that dough was baked in one loaf! The fun part was decorating the tops with pine nuts.

The finished product was very nicely browned loaves of dense cake/bread. I drizzled them with honey and then used some for dipping. I would recommend keeping a lot of honey on the side when eating this. I thought that the bay leaves were going to give it a little more flavor, but overall the taste of the bread is very neutral.

What I learned: If I were part of an ancient civilization, I would have worshiped honey because it makes even the simplest of breads sugary and delectable.

Jessie Carrillo, Manager of Adult Programs

From the moment I saw Vatia’s Fig-Stuffed Pastry Piglets, I knew I had to make them. While not directly drawn from an ancient source, this dish is not too far off from something that the Romans would have eaten, and the combination of ingredients sounded tasty.

I started by making a dough from whole wheat flour, olive oil, and water. While the dough rested in the fridge, I sliced two portions of pork tenderloin, pounded them with a meat mallet until they were very thin, and seasoned them.

Next I combined dried figs with salt, pepper, and honey in a food processor, spread the mixture on the pork pieces, and then rolled them up like a couple of Ho Hos®. I rolled out my dough until it was about the thickness of a pie crust and cut pieces large enough to wrap around the pork, as well as some smaller pieces that I fashioned into my piglets’ ears, noses, and tails.

After wrapping each piece of pork in pastry and decorating the piglets, I followed the author’s advice and threw them into the oven without naming them. After about 30 minutes at 400 degrees, the piglets came out sadly missing their tails, but otherwise adorable and surprisingly yummy!

What I learned: Meat wrapped in pastry dough has always been delicious, and cooking is even more fun when you combine it with sculpture.

Stacey Lizotte, DMA League Director of Adult Programs

I decided to make Apicius’ Tiropatina (Tiropatinam), which is an egg custard, because it only had three ingredients (six if you count the garnishes), and because I was curious about what flavor and texture you would get in a custard from just eggs, milk, and honey (instead of sugar).

You would think three ingredients would make this a simple recipe, but it was VERY time consuming—literally a two-day process (so if patience is not a virtue of yours, I wouldn’t recommend this recipe).

Once the three ingredients were combined, there was a lot of custard mixture—A LOT. There was no way the mixture I had would only make 18 small custards like the recipe said. If you want to make that amount, I would recommend at least halving this recipe. The one step I added is that I strained my custard mixture before putting it in the tins. I do this for any custard or curd that I make, and I feel that it’s important in order to get a smooth texture.

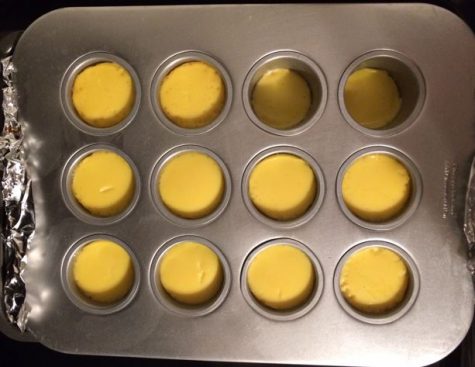

I didn’t have a pudding tin and my muffin pans were too large to put in a water bath, so I decided to use my mini cheesecake pan. I didn’t take into account how watery this mixture is compared to a cake batter so, as you can see, during the baking process a few of my custards seeped out of the pan.

I often find egg custards too “eggy” for my taste, but these custards actually had a light flavor that I found appealing. I attribute that to the honey. I also enjoyed the black pepper on top—clearly those Romans knew what they were doing.

What I learned: A water bath is essential for baking custards. Since I had so much extra batter, I decided to make a batch of custards in a muffin tin but without a water bath and the result was horrible.

If you would like to learn more about Roman cooking and enjoy a Roman Feast, you can purchase your tickets for the event here.