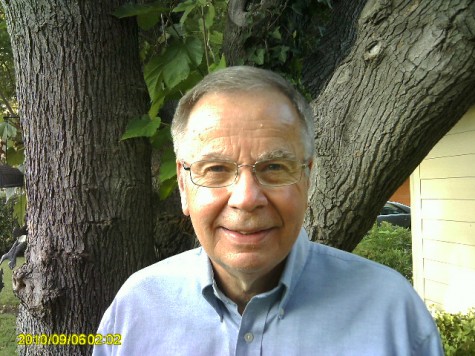

Known as the “Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages,” Dr. Patrick McGovern is a world-renowned expert on the origins of ancient fermented drinks and a leader in the emerging field of biomolecular archaeology. On Thursday evening, he will present the history of wine in a lecture entitled Uncorking the Past, part of the Museum’s Boshell Family Lecture Series on Archaeology. Dr. McGovern tells us more about his unique archaeological research.

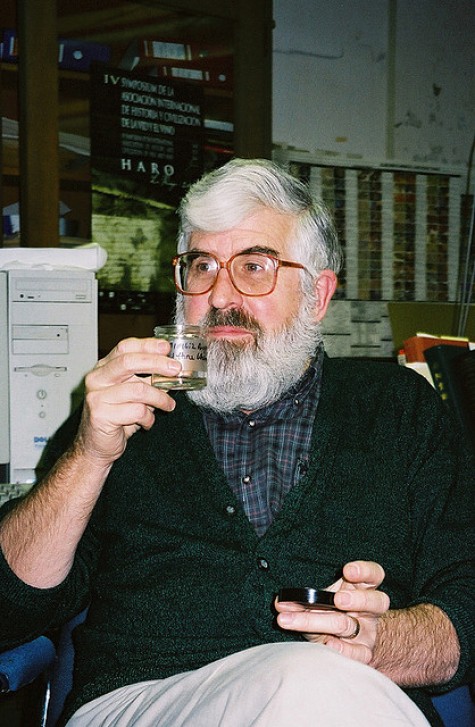

Dr. McGovern in his laboratory, examining a 3000-year-old millet wine, which was preserved inside a tightly lidded bronze vessel from a Chinese tomb. Photo: Penn Museum.

You oversee the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology – a leader in this cutting-edge field. What type of research do you conduct at the lab?

The Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory has been at the forefront of the revolution in uncovering the organic underpinnings of our species on this planet. We analyze ancient fermented beverages, foods, perfumes, dyes (such as Royal Purple), and other organics, which could only be imagined from ancient writings, using highly sensitive instruments in the laboratory (infrared spectrometry, gas and liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, etc.). Molecular archaeology promises to open up whole new chapters relating to our human ancestry and genetic development, cuisine, medical practice, and other crafts over the past two million or more years.

Where do you find evidence of ancient food and drink, and what tools and technologies do you use to analyze that evidence?

Pottery, which is virtually indestructible and goes back to between 5000 and 13,000 B.C. in various parts of the world, absorbs ancient organics and is crucial to our research. By using organic solvents, we “tease out” the ancient organics, and then go to work with our battery of scientific instruments. Sometimes we work directly from residues, either deposited inside vessels of various materials or deposited elsewhere (e.g., on bones, textiles, etc.).

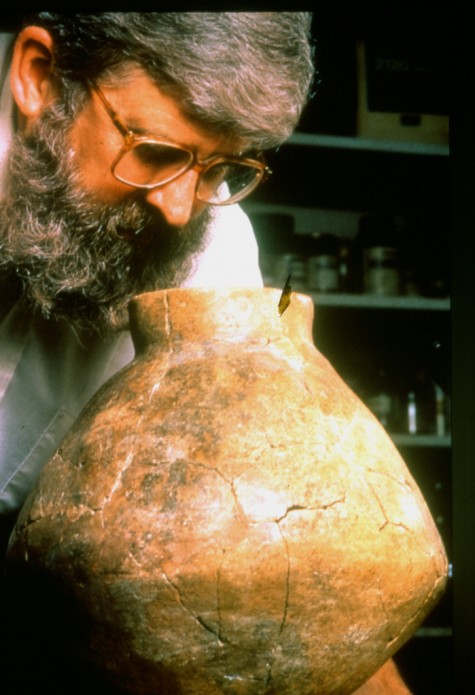

Dr. McGovern peers into a wine jar dating to 5400 - 5000 B.C. Photo: courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

In the course of your work, what has been your most surprising discovery?

There have been many, but the discovery of Royal Purple and the earliest resinated wine from Iran (circa 5400 B.C.) are two highlights.

Your academic background is varied, and you have degrees in both chemistry and archaeology. How did you become interested in the history of fermented beverages?

It was very serendipitous. As I moved from inorganic to organic chemical analysis of archaeological materials, we were successful in first detecting Royal Purple, a highly stable compound that had been preserved for over 3,000 years. This gave us the confidence to move on to wine, beer, and other materials. Grape wine was first, and came about when an associate, Virginia Badler, showed us shards of large jars from an early Iranian site (Godin Tepe) with residues inside that she believed to be wine deposits. She proved to be right, and the rest is history.

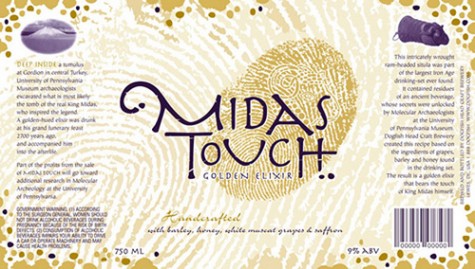

After the lecture on Thursday, we will have the opportunity to sample wines from Burgundy, as well as an artisan beer called Midas Touch. Please tell us about the beer, which was inspired by analysis you did on objects found in the tomb of the legendary King Midas.

It all started over fifty years ago with a tomb, the Midas Tumulus, in central Turkey at the ancient site of Gordion, which was excavated by the Penn Museum in 1957. Within that tomb, buried deep down in the center of a large mound, excavators found the body of a 60- to 65-year-old male, who had died normally. He lay on a thick pile of blue- and purple-dyed textiles, the colors of royalty in the ancient Near East. The excavators had found what would become one of the most spectacular archaeological discoveries of the 20th century – they had located what has since been identified as the tomb of Gordion’s most famous son, King Midas.

“King Midas” laid out in state on piles of purple- and blue-dyed textiles inside his coffin, from the northwest, with the large bronze drinking set in the background. Photo: courtesy of the Gordion Project, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Inside the tomb, surrounding the body, were 157 bronze vessels, including large vats, jugs, and drinking bowls that had been used in the final farewell dinner for the king outside the tomb. The body was then lowered into the tomb, along with the remains of the food and drink, to sustain him for eternity.

Surprising, none of the 157 drinking vessels were made of gold. Where then was the gold if this was the burial of Midas with the legendary golden touch? In fact, the bronze vessels, once the bronze corrosion was removed, gleamed just like the precious metal. The real gold, as far as I was concerned, was what these vessels contained – the remains of an ancient beverage, which was intensely yellow, just like gold. Chemical analyses of the residues – teasing out the ancient molecules – provided the answer: the beverage was a highly unusual mixture of grape wine, barley beer, and honey mead.

Jars filled with the spicy stew, served at the funerary feast of King Midas, can be seen inside one of the large vats. They were placed there after the fermented beverage, which they initially contained, had been served at the funerary banquet. These “left-overs” might have been intended for sustenance for the king in the afterlife. Photo: courtesy of the Gordion Project, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

You may cringe at the thought of mixing together wine, bee,r and mead, as I did originally. That’s when I got the idea to do some experimental archaeology. In essence, this means trying to replicate the ancient method by taking the clues we have and trying out various scenarios in the present. In the process, you hope to learn more about how the ancient beverage was made. To speed things up, I also decided to have a competition among microbrewers to try to reverse-engineer and see if it was even possible to make something drinkable from such a weird concoction of ingredients. Soon, experimental brews started arriving on my doorstep for me to taste – not a bad job, if you can get it, but not all the entries were that tasty.

Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head Brewery ultimately triumphed. The beverage has since gone from one triumph to the next. Dogfish is the fastest growing microbrewery in the country, and “Midas Touch” has become its most awarded beverage.

Be sure to watch Dr. McGovern and the team from Dogfish Head Brewery on The Discovery Channel’s Brew Masters, which chronicles their travels around the world searching for exotic ingredients and discovering ancient techniques to produce their award-winning beers.

Patrick E. McGovern is Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. His books include Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture and Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages. His research on the origins of alcoholic beverages has been featured in Time, the New York Times, the New Yorker, Nature, and numerous other publications.