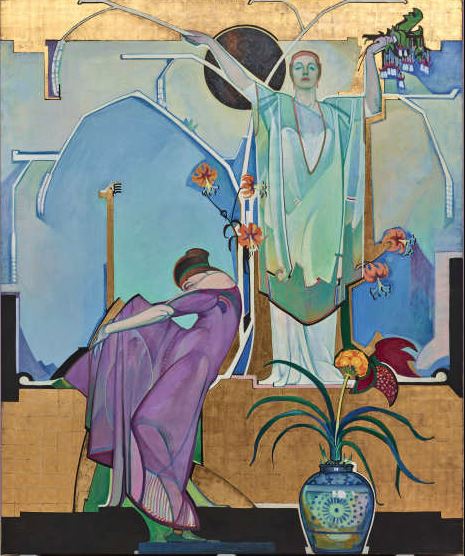

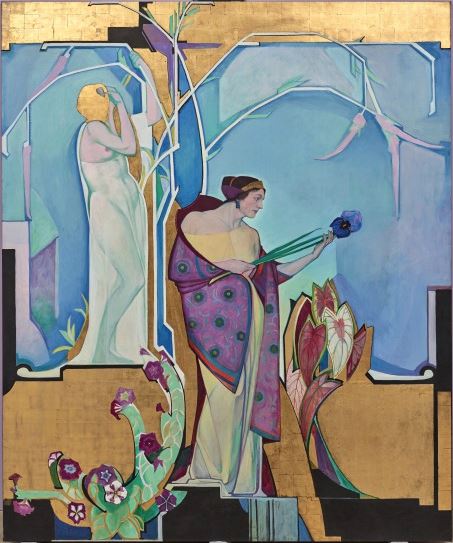

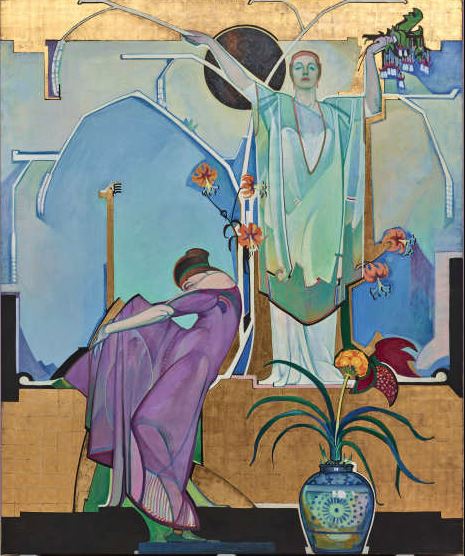

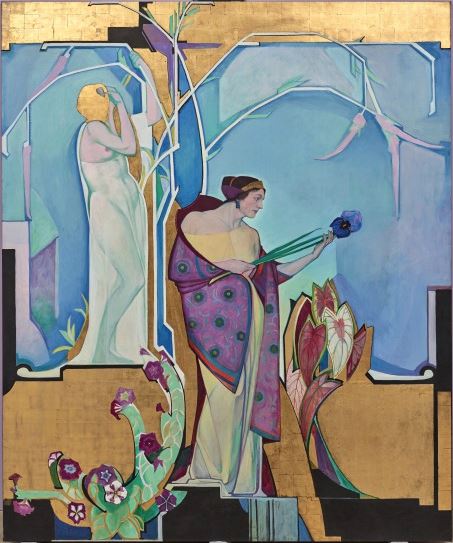

For the past several months, the Rachofsky Quadrant Gallery on the Museum’s first level has been occupied by seven large paintings spanning half the gallery, nearly floor to ceiling. Installed on a lilac-colored wall, the framed canvases contain figures posed with flowers, rendered in eye-catching pastel hues, and surrounded by alternating sections of black and gold leaf.

These paintings are Edward Steichen’s In Exaltation of Flowers, a commissioned series that the artist completed in 1914 for the home of New York financier Eugene Meyer and his wife, Agnes. Never installed in the space for which they were created, the majority of the panels were kept in storage for the past century. Last summer, the DMA’s conservation team unrolled the canvases, stretched and framed them, and completed conservation treatment so the series could go on tour. Newly conserved and reunited in one exhibition, In Exaltation of Flowers is a time capsule of Edward Steichen’s life and the lives of his close friends on the eve of World War I.

On Thursday, April 26, from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m., we will say goodbye to In Exaltation of Flowers with a soiree that will include a complimentary reception with drinks and small bites inspired by the paintings, a tour about flower symbolism with Dallas Arboretum VP of Gardens Dave Forehand, and a talk by art historian Dr. Jessica Murphy.

Reception

6:00 p.m., Check in at Will Call, Horchow Auditorium, Level 1

Arrive early for a complimentary reception featuring beer, wine, and small bites inspired by In Exaltation of Flowers and Edward Steichen’s French country garden. Hors d’oeuvres will include:

FRESH PEA AND MINT SHOOTER

butter-poached shrimp and hibiscus crema

DRIED FIG AND BRIE CROSTADA

balsamic glaze

GRILLED QUAIL AND SUNDRIED CHERRY SALAD

chive crepes and saffron aioli

ROASTED RED & GOLDEN BEETS WITH TEXAS GOAT CHEESE

arugula and orange-tarragon dressing

PARSLEY CHICKEN IN PHYLLO

romesco sauce

ROSE AND WHITE CHOCOLATE MOUSSE

candied rose petals and toasted almonds

Tour: In Exaltation of Flowers

6:30 p.m., Meet at the Flora Street Visitor Services Desk, Level 1

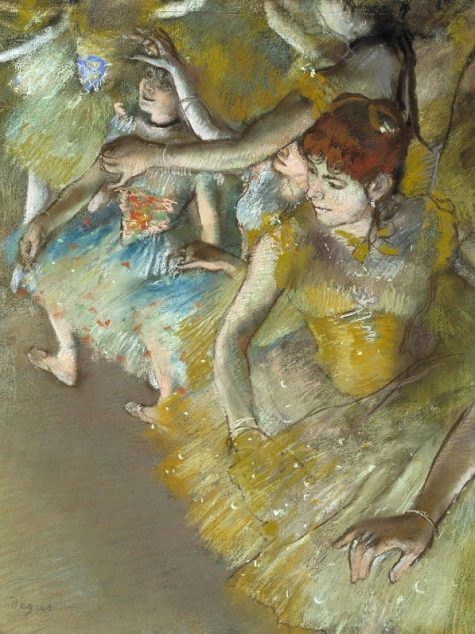

Edward Steichen was an avid gardener who exhibited his celebrated delphiniums in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. For Steichen and much of society at this time, flowers were more than just beautiful objects; they took on human character traits and the giving or receiving of flowers served as a kind of subtle language. Each of the sitters for In Exaltation of Flowers is paired with specific flowers that relate to their personalities or the nicknames given to them within their friend group. Join Dave Forehand of the Dallas Arboretum for a tour of In Exaltation of Flowers focusing on the types of flowers Steichen included in his paintings and what they might have communicated to a viewer in 1914.

Exhibition Talk: Murals from a “Magic Garden”: Edward Steichen’s “In Exaltation of Flowers”

7:00 p.m., Horchow Auditorium, Level 1

In Exaltation of Flowers captures a very particular moment in Edward Steichen’s career, in the history of art, and in the lives of a circle of friends on the eve of the World War I. A very personal project for the artist, the murals include portraits of close friends, either painted from life or from photographs, alongside flowers inspired by his garden at the French country home where he hosted lively parties. Steichen’s careful portrayal of his subjects reveals the nuances of their personalities and relationships within the social group. Best remembered as a photographer, Steichen had a somewhat rocky relationship with painting and ultimately destroyed much of his painted work. His approach to this series shows a nod toward the Symbolist movement, with its emphasis on flatness, invariable color, and in some sections abandonment of realism. Jessica Murphy, Brooklyn Museum’s Manager of Digital Engagement, will bring to life these and other stories behind Edward Steichen’s murals and the people who inspired them.

Don’t miss your chance to spend an evening in 1914 with Edward Steichen and his closest friends before In Exaltation of Flowers leaves the DMA in early May. For more information, visit DMA.org or click here to purchase a $5 ticket.

Jessie Carrillo is Manager of Adult Programs at the DMA.