Over the past two weeks, the DMA’s Hoffman Galleries have been populated with sculptures that appear—for lack of a better word—unfinished. Amorphous mounds of pastel-washed, unfired clay occupy the sunlit central gallery. Wall-mounted vitrines house bits of Polystyrene and bark, which mingle with squiggles of neon and fragments of clay. In the back room, configurations of Cor-ten steel sheets lie in delicate balance, punctuated unexpectedly by soft, fluffy pompoms. To the naked eye, these works could be mistaken for preliminary models or sculptural prototypes rather than polished final products—and that is exactly what Rebecca Warren, the British artist responsible for these enigmatic sculptures, wants.

Rebecca Warren: The Main Feeling installation, March 2016

On March 13, Rebecca Warren: The Main Feeling opened to the public at the DMA. The artist’s first comprehensive museum show in the US, the exhibition surveys over ten years of her sculpture practice, which intentionally confounds categorization and challenges existing histories of art. In other words, Warren takes all that we expect of sculpture, and flips it on its head.

Rebecca Warren: The Main Feeling continues the DMA’s commitment to supporting the work of innovative female sculptors, many of whom continue to be under-recognized within the history of art. Below are a few highlights of sculptures made by female artists from our contemporary art collection, all of which are currently on view.

Barbara Hepworth, Figure for Landscape, 1960, bronze, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Inc., 1983.154, © Alan Bowness, Estate of Barbara Hepworth

In our Sculpture Garden, British artist Barbara Hepworth’s Figure for Landscape stands stoically along the west wall. An early pioneer of abstract sculpture, Hepworth modeled this biomorphic form and then cast it in bronze, leaving gaping openings in the work that distinguish positive and negative space within the body of the structure. While sculpture making had traditionally been conceived as the production of an object in space, Hepworth illuminated the possibility of sculpture making as a process of carving out space within an object.

(left to right) Yayoi Kusama, Accumulation, 1962-64, sewn stuffed fabric with paint on wooden chair frame, The Rachofsky Collection and the Dallas Museum of Art through the DMA/amfAR Benefit Auction Fund, 2008.41, © Yayoi Kusama; Yayoi Kusama, Untitled, 1976, shoes, paint, and foam, Dallas Museum of Art, bequest of Dorace M. Fichtenbaum, 2015.48.22.a-b

Two works by Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama are on view in the new installation Passages in Modern Art: 1946-1996. Kusama is known for her uncanny ability to imbue everyday objects such as chairs, shoes, and vegetables with the psychological intensity of dreams and fantasy. To make Accumulation, Kusama coated a wooden chair frame with phallus-like fabric forms and subsequently painted every component of the work in a neutral beige color. Untitled comes from the same series, and similarly features shoes that have been covered in phallic foam cutouts.

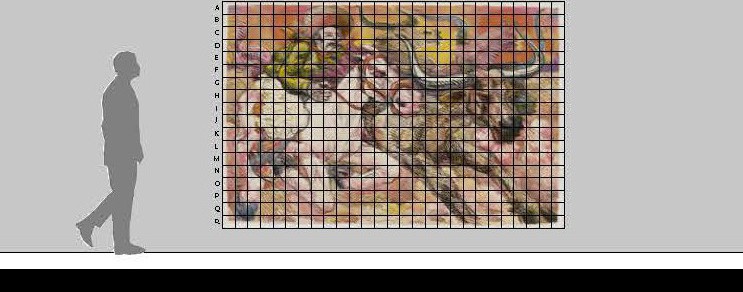

Anne Truitt, Come Unto These Yellow Sands II, 1979, acrylic on wood, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Shonny and Hal Joseph (St. Louis, Missouri) in honor of Cindy and Armond Schwartz, 2002.55, © Estate of Anne Truitt

A major figure in American art since the 1960s, Anne Truitt is best known for her streamlined vocabulary of basic forms and colors, which typically coalesced into tall, thin wooden sculptures meticulously coated in several smooth layers of paint, such as Come Unto These Yellow Sands II, currently on display in the Barrel Vault. A nearly eight-foot pillar of deep, vivid blue, Truitt’s sculpture projects a three-dimensional block of color into the space of the viewer, merging the optical experience of her work with sensuous immediacy.

Nancy Grossman, Untitled (Head), 1968, leather, wood, and metal, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1969.8.a-b

Installed adjacent to Truitt’s column of pure blue is Nancy Grossman’s Untitled (Head), a sculpted head carved from wood and overlaid with leather. Rendered blind and mute, this unsettling figure alludes to the role of the silent witness amid cruelty and disorder within contemporary society. In fact, Grossman began making these head sculptures in the 1960s partially in response to the violence and social upheaval caused by the Vietnam War.

Sculpture takes center stage this season at the DMA, so the next time you find yourself at the Museum, be sure to take a closer look at these works in Rebecca Warren: The Main Feeling and Passages in Modern Art: 1946-1996.

Nolan Jimbo is the McDermott Intern for Contemporary Art at the DMA.