What makes a best friend? There are some common traits associated with a BFF: someone who knows you better than anyone else, someone who accepts you, someone who is honest and forgiving, someone who listens and offers advice, and someone who is trustworthy. We all have best friends, so it isn’t surprising that artists do too. But it is special when two artists share that closeness because their friendship influences each other’s work. In honor of National Best Friends Day, we are highlighting some of the artistic friendships represented in the DMA’s collection.

Vincent van Gogh, Sheaves of Wheat, July 1890, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection 1985.R.80

Emile Bernard, Breton Women Attending a Pardon, 1892, oil on cardboard, Dallas Museum of Art, The Art Museum League Fund 1963.34

Vincent van Gogh and Emile Bernard met in the mid-1880s, when Bernard was 18 years old and van Gogh 15 years his senior. Both artists were greatly influenced by Japanese art—Bernard by the simplicity and flat forms and van Gogh by the spatial effects, strong color, everyday objects, and detailed depictions of nature. The friends corresponded through mail, often sending each other drawings and discussing their artistic ideas. In 1889, following van Gogh’s highly critical response to Bernard’s Christ in the garden of olives, their correspondence ceased; however, after van Gogh’s death Bernard wrote the first published biography on Vincent van Gogh.

Octavio Medellín, Smoky Celadon, n.d., glazed stoneware, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1949.36

Carlos Mérida, Dancers of Tlaxcala, 1951, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1951.108

Octavio Medellín met Guatemalan painter Carlos Mérida in Mexico in the late 1920s. The friends traveled together and taught at North Texas State (now University of North Texas) from 1941 to 1942. Though Mérida eventually returned to Mexico, the two remained close friends and influenced each other’s work until Mérida died in 1985.

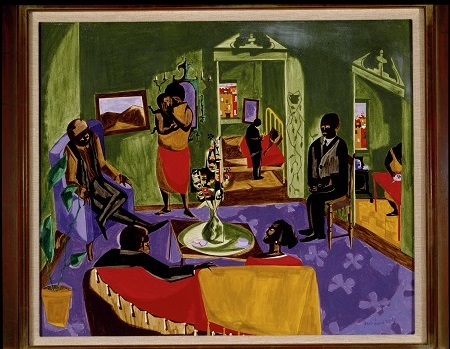

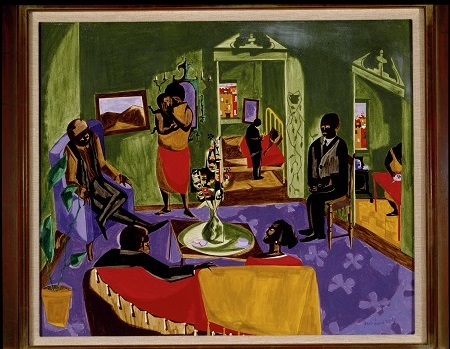

Jacob Lawrence, The Visitors, 1959, tempera on gessoed panel, Dallas Museum of Art, General Acquisitions Fund, 1984.174

Romare Bearden, Soul Three, 1968, paper and fabric collage on board, Dallas Museum of Art, General Acquisitions Fund and Roberta Coke Camp Fund, 2004.11

Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence grew up in Harlem following the Harlem Renaissance and were profoundly influenced by the music, literature, and culture of their neighborhood. As young men, both participated in various community-based art classes and workshops in the area and were inspired by writer and philosopher Alain Locke. The two corresponded throughout the years, and some of their letters are available through the Archives of American Art.

-

-

Otis Dozier, “Mexican Landscape (adobe),” 1963, oil on Masonite, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The Dozier Foundation, 1990.46

-

-

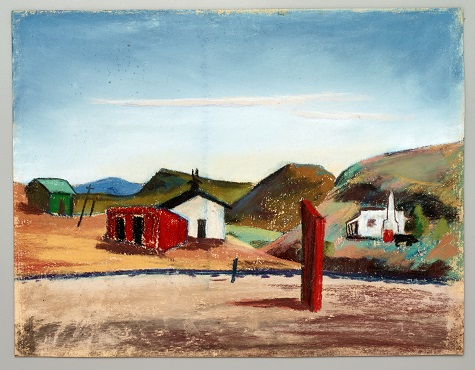

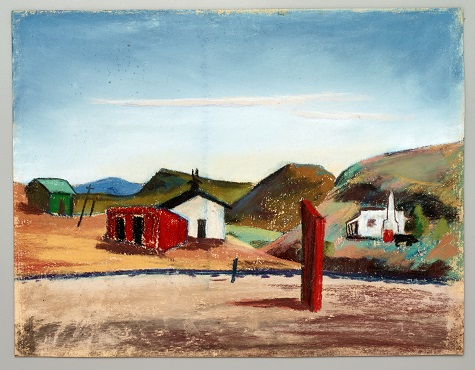

Velma Davis Dozier, “Terlingua,” n.d., pastel on sandpaper, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Denni Davis Washburn and Marie Scott Miegel, 1990.21

-

-

Barney Delabano, “Shadowed Light,” 1950, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1950.52

Barney Delabano studied under Otis Dozier when he attended Southern Methodist University and then the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts School in the late 1940s. Over time, Dozier and his wife, Velma, came to be Delabano’s close friends. The Doziers would even come to be mentors for Barney Delabano’s son, artist Martin Delabano.

-

-

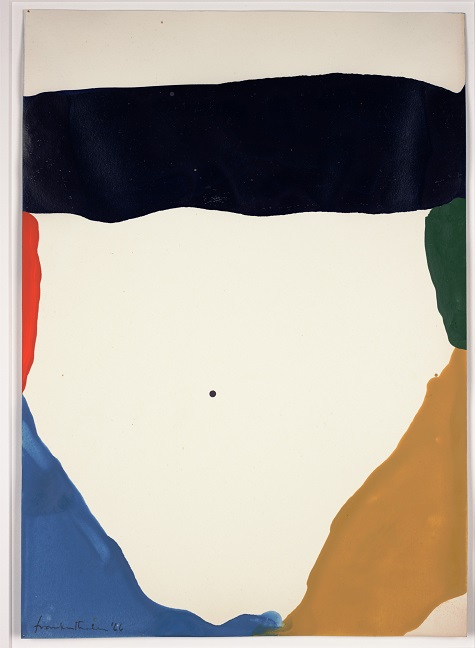

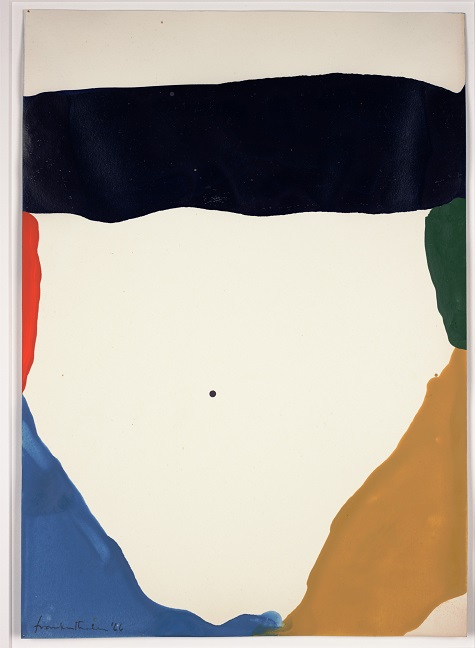

Helen Frankenthaler, “Possibilities,” 1966, acrylic on paper, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Tucker Willis, 1998.105

-

-

David Smith, “Untitled,” 1962, spray paint on paper, Dallas Museum of Art, Contemporary Art Fund, General Acquisitions,1986.58

Helen Frankenthaler and David Smith were first introduced by art critic Clement Greenberg in 1950. Throughout their 15-year friendship, they not only visited each other’s studios and corresponded through mail but even vacationed together with their families. They remained close friends until Smith’s death in 1965.

Jessica Fuentes is the Manager of Gallery Interpretation and the Center for Creative Connections at the DMA.