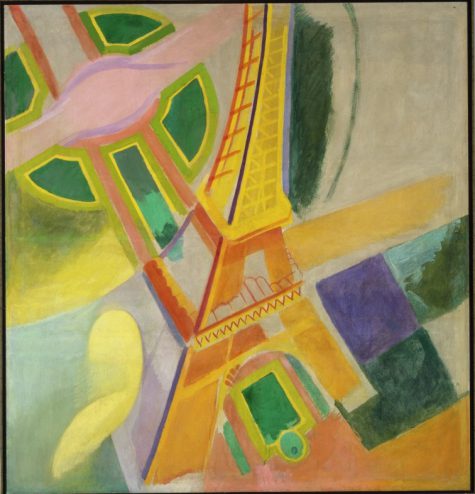

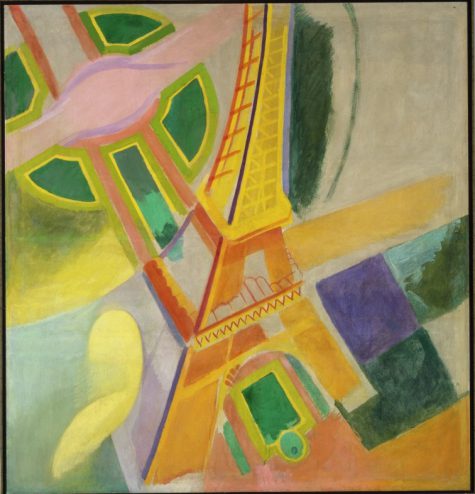

Robert Delaunay, Eiffel Tower, 1924, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, 1981. 105, © L & M Services B. V., Amsterdam

Bastille Day is this Thursday, but the revolution will last an extra day as we continue the festivities during our July Late Night.

To help you practice your French numbers, here are some things you can experience that evening:

Un – The number of movies starring Kirsten Dunst that will be screened (spoiler alert: it’s Marie Antoinette).

Deux – The number of people facing off against each other in our fencing and dueling demonstrations.

Trois – The number of hours DJ Wild in the Streets will spin a mix of eclectic French music.

Quatre – The number of tours that will explore the French Revolution, fashion, and portraiture.

Cinq – The number of hours you can hear live French music performed by local musicians.

Six – The time that Late Night starts, so don’t être en retard!

Sept – The start time for our Late Night Talk sharing a quick history of the French Revolution.

Huit – The number of selfies you should take in front of French portraits in our Rosenberg Collection, and then share them on our Instagram with #DMAnights.

Neuf – The number of rogue mimes you might see walking around.

Dix – The number of times DMA staff might yell “vive la DMA!” during the evening.

Jean Antoine Theodore Giroust, The Harp Lesson, 1791, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, Mrs. John B. O’Hara Fund, 2015.10.FA

In addition to our Late Night, Bastille Day Dallas will expand its annual celebration and bring more French culture to the Dallas Arts District with outdoor activities on Flora Street. So put on your beret, grab a baguette, and join us!

Stacey Lizotte is Head of Adult Programming and Multimedia Services at the DMA.