Cultural exchange takes many forms, historically ranging from forced interaction in war, colonization, slavery, and looting, to the peaceful sharing of items, ideas, and practices. With this nuanced transformation of “cultural exchange” over time, I’d like to offer a sneak peek into the abundance of it in the DMA’s upcoming exhibition, The Power of Gold: Asante Royal Regalia from Ghana. The Asante still exist today with many traditions and international influences, so I hope you recognize a few in the show.

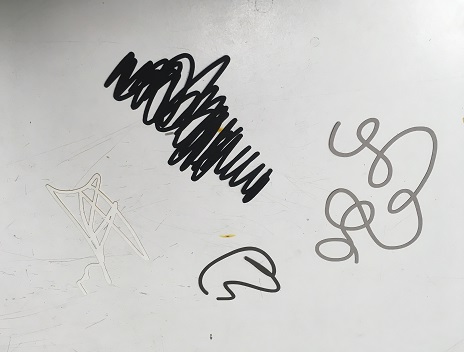

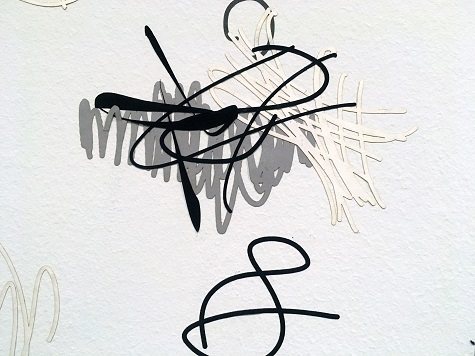

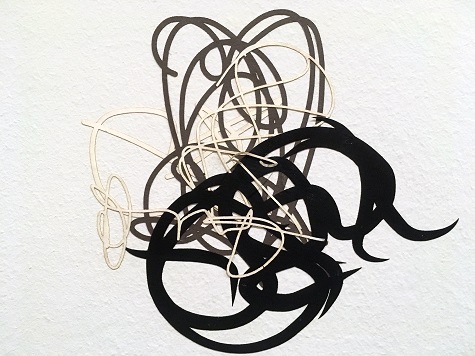

A subgroup of the Akan peoples, the Asante established their empire (1701-1957) in modern-day Ghana. Especially after the 14th century, trans-Saharan trade increased interaction between the Akan in West Africa and Arab and Berber merchants of the Middle East and North Africa, who brought not only salt in exchange for gold, but also the Arabic language and Islamic aesthetic, too. Compare this 12th century Iranian inkwell to this Asante casket kuduo:

- Inkwell (side), Iran, late 12th century, brass inlaid with silver and copper, The Keir Collection of Islamic Art, K.1.2014.73.A-B.

- Inkwell (lid), Iran, late 12th century, brass inlaid with silver and copper, The Keir Collection of Islamic Art, K.1.2014.73.A-B.

- Kuduo, Asante peoples, late 19th-early 20th century, copper alloy, Dallas Museum of Art, African Collection Fund, 2017.9

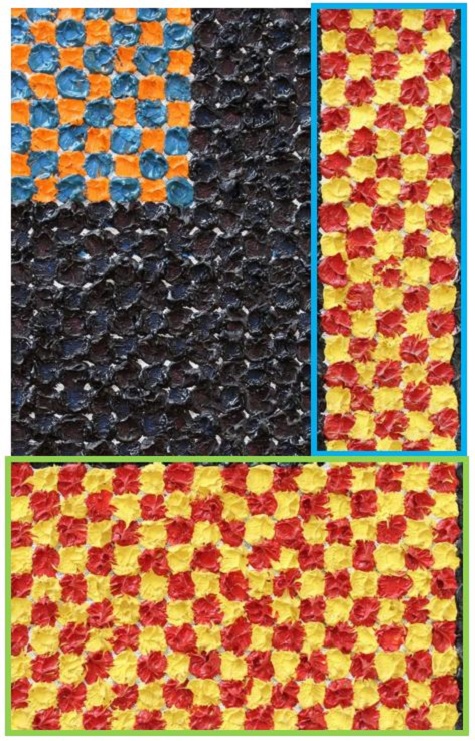

Shared elements include the brass material, structural shape, and various etchings decorating the surfaces. Function differed according to needs and tastes: the inkwell for writing, and the kuduo for storing gold dust and nuggets. Calligraphy encircles the inkwell lid, yet also seems to be absorbed into the body of the kuduo, alongside medallions and floral motifs. The Asante found inspiration in Islamic art and calligraphic linearity, mixing a love of geometric patterns with newly adapted horizontal bands of sectioned patterns. These abstract qualities may then illustrate Asante reflections on their past and contemporary sights, in hopes of replicating imagery seen on merchants’ goods, since Islamic influence remained strong throughout the centuries.

Muslims were not the only ones to influence Asante cultural production; 19th century colonizers also imparted their imagery on West Africa. The Asante have a wide array of traditional proverbs and imagery that form the “verbal-visual nexus.” This link probably developed alongside Akan hierarchies, so that royal regalia and materials could help visibly demonstrate the grandeur of kingship. Visible signs range from items like books and foodstuffs, to animals such as porcupines, crocodiles, and leopards.

Proverbs describe aspects of life that can be understood as advice or lessons for the community. Here’s one: “When rain beats on a leopard it wets him, but it does not wash out his spots.” In terms of the leopard’s spots being washed away, this may reference the careful attention a king gives to his character, so as not to ruin his reputation in the kingdom. The British Empire brought with them to Ghana their royal coat of arms, which is thought to have popularized the lion in Asante art. Representations of the Asantehene (ruler, king) thus shifted from the leopard to the lion, as seen in this proverb: “A dead lion is greater than a living leopard.” So, even stemming from colonial presence, we see the Asante adopting desirable foreign elements and making them their own.

Sword ornament in the form of a lion, Asante peoples, Ghana, Africa, c. mid-20th century, cast gold and felt, Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc. 2010.2.McD

A final example of exchange can be found in our very own backyard. In 1991, Nana Lartey Kwaku Esi II, the crowned head of the Asona (another subgroup of the Akan), enstooled four African Americans in Dallas, bringing Ghanaian royalty to the Metroplex. The enstooled are tasked with disseminating a love of the homeland and possess some of their own royal regalia, including gilded hats and footwear and kente cloths. In addition to sharing uplifting words, such as “we are all one human being under God,” Nana Lartey Kwaku Esi II sought to ensure that African culture, in a Ghanaian context, was shared with those in the U.S. that wish to reclaim their roots. These actions demonstrate the depth and spread of cultural influence in our country and prove that the Asante not only have a living culture, but also ideas worth spreading.

To learn more about the Asante, check out these resources:

- Doran H. Ross, The Arts of Ghana (Regents of the University of California: Los Angeles, 1977), 9-10.

- Robert Sutherland Rattray, Ashanti Proverbs: The Primitive Ethics of a Savage People (Clarendon Press: London, 1916), 63.

- Doran Ross, Gold of the Akan from the Glassell Collection (Merrell Publishers, 2003), 67.

- James D. Webster, Dallas Weekly, Ghana to Dallas: A Royal Exchange is Coming to America (Oct. 10-16, 1991), 13.

- Raymond A. Silverman, Akan Transformations: Problems in Ghanaian Art History, edited by Doran H. Ross and Timothy F. Garrard (Regents of the University of California: Los Angeles, 1983).

Tayana Fincher is the McDermott Intern for African Art at the DMA.