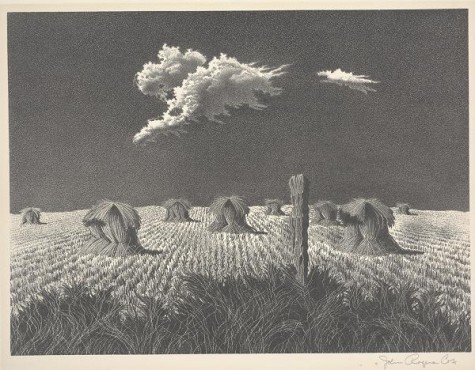

Once again, the Works on Paper Gallery on the Museum’s second level is being reinstalled. Fourteen drawings, lithographs, etchings, and engravings by some of the 20th century’s greatest artists—Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti, Pablo Picasso, and many more—will adorn the gray walls.

The new installation, titled Linear Possibilities in Modern European Prints, didn’t come together overnight. I’ve been working on it for the last six months, and I am now very excited (even a bit nervous) to present it to the Museum’s public. The idea came to me after looking many times through the Museum’s collection of European works on paper, which includes over 2,000 prints, drawings, and photographs dating from the late 1400s to the 1980s.

Henri Matisse, Loulou, 1914, etching, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of the Wendover Fund, © 2013 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I had to work with a few limiting factors before finding my final concept. The three walls of the gallery can only accommodate a certain number of works comfortably, so I had to keep the number within a range of eight to fourteen works. Also, works on paper are very sensitive to natural light. The longer a work is on view, the more damage that occurs, causing the paper to darken and certain media to fade. Therefore, I couldn’t use any work that had recently been on view. I found a few possibilities based on particular themes or artistic movements before choosing to investigate lines, one of art’s most basic elements.

Alberto Giacometti, Annette in the Studio, 1954, lithograph, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred L. Bromberg, © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

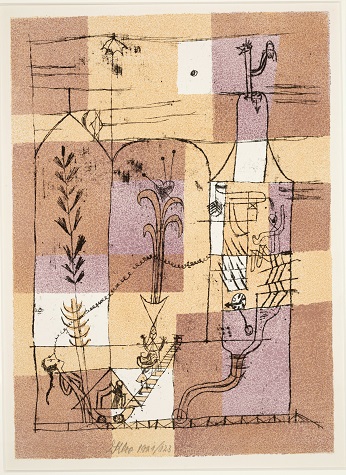

The idea was influenced by a great quote from the Swiss artist Paul Klee: “A line is a dot that went for a walk.” Lines appear in many types and sizes: vertical, horizontal, zigzagged, curvy, squiggly, thick, thin, long, short. When combined, lines reveal spaces or forms and allude to volume or mass. They can possess emotive qualities as well as imply movement.

Paul Klee, Hoffmanesque Scene, 1921, color lithograph, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Stuart Gordon Johnson by exchange; General Acquisitions Fund; and The Patsy Lacy Griffith Collection, gift of Patsy Lacy Griffith by exchange, (c) Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

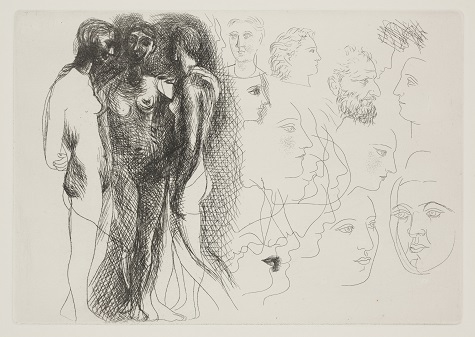

Pablo Picasso, Three Standing Nudes (left) and Sketches of Heads (right), 1927, etching, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, © 2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The works in the installation demonstrate how painters and sculptors of the European avant-garde turned to drawing and printmaking in a new manner, creating with nothing but lines. They explored the possibilities of rhythmic or abstracted sequences of delicate, robust, and expressive lines in their compositions of a nude, an artist’s studio, or more abstracted scenes. There is an astonishing beauty to be found in these prints and drawings by Matisse, Giacometti, Picasso, and others. I encourage you to visit the Dallas Museum of Art (general admission is free!) to see these amazing and innovative works.

Linear Possibilities in Modern European Prints goes on view in the European Art Galleries on Level 2 Sunday, March 17.

Hannah Fullgraf is the McDermott Graduate Curatorial Intern in European Art at the DMA.

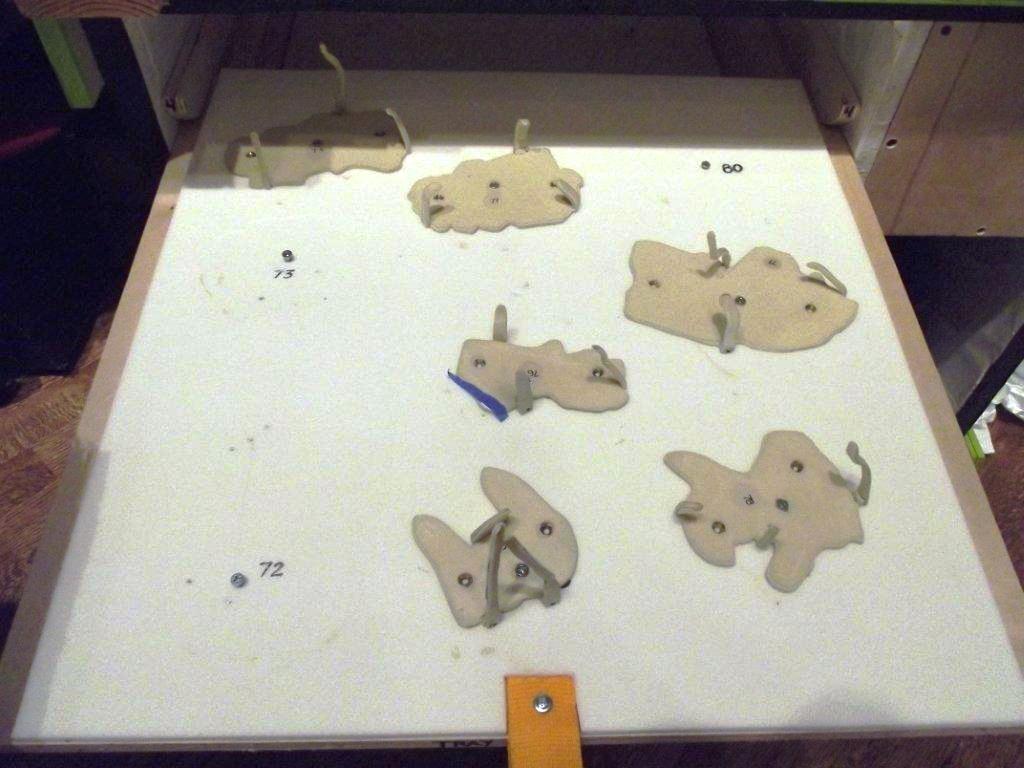

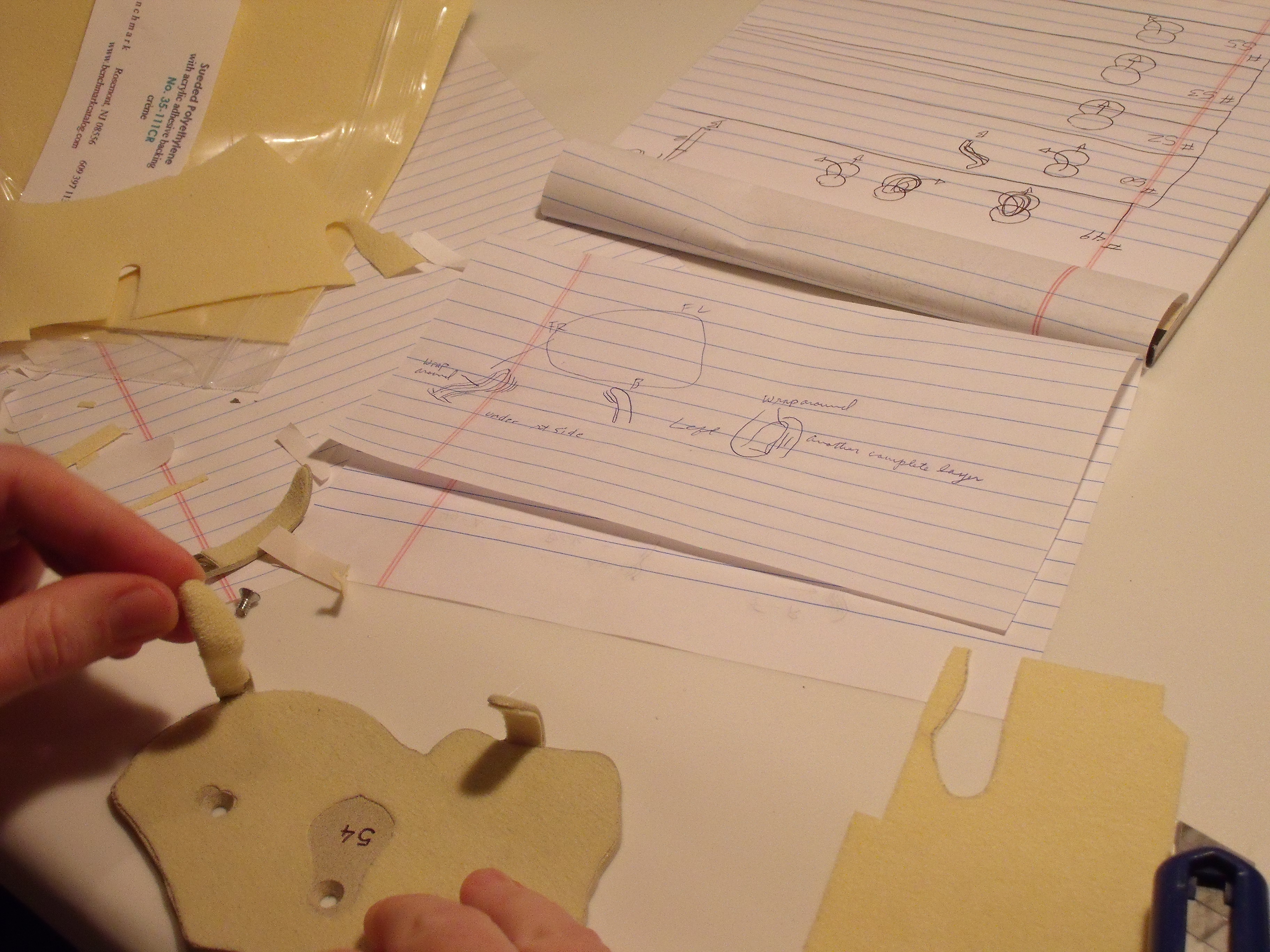

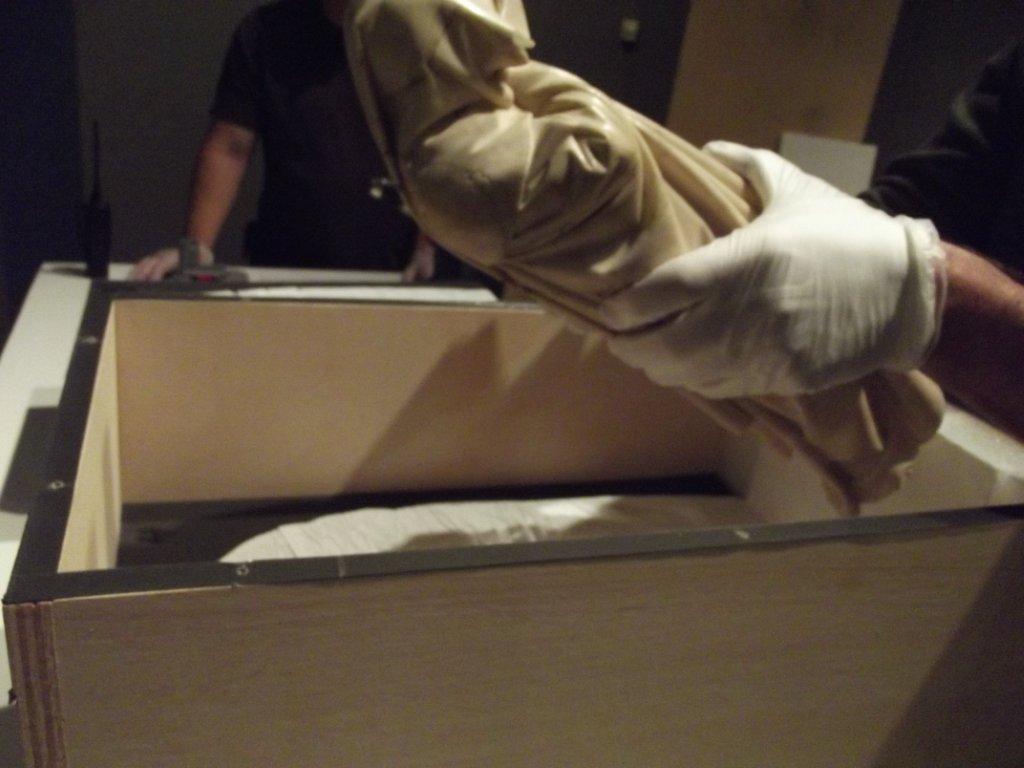

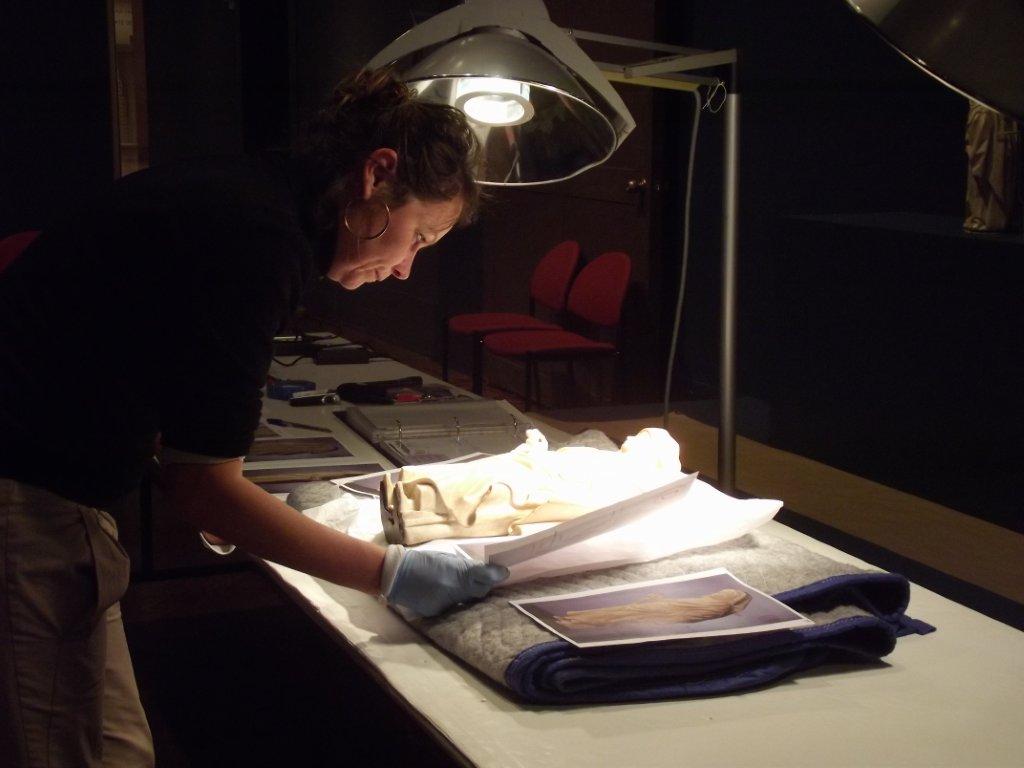

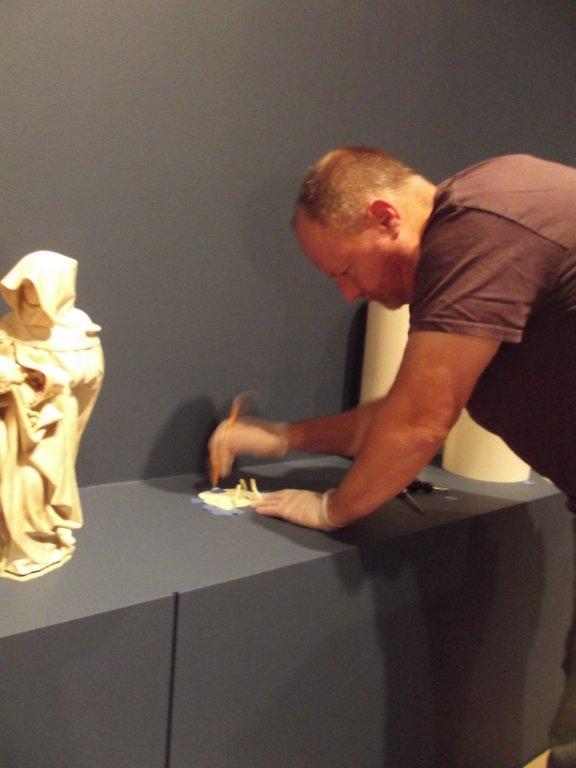

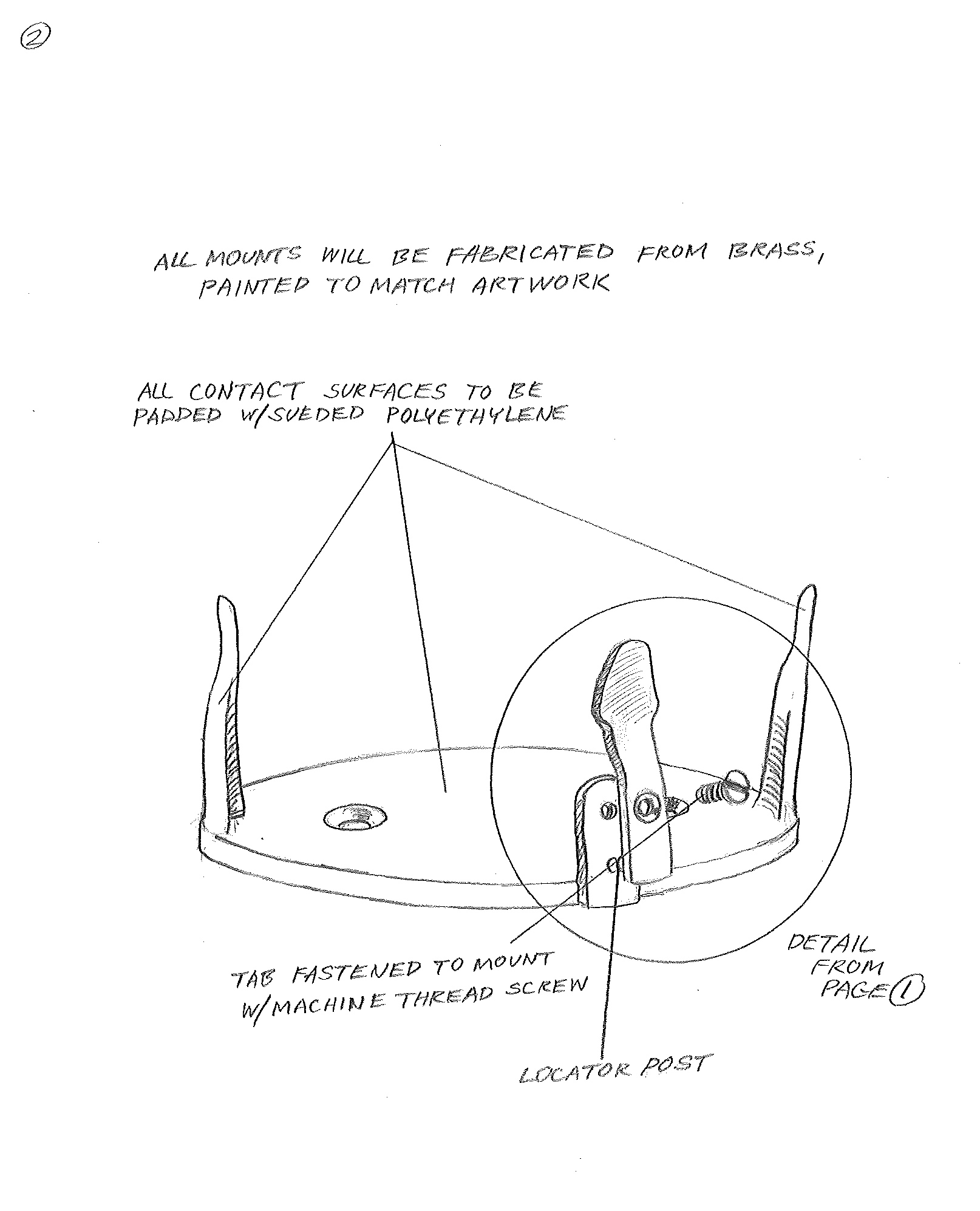

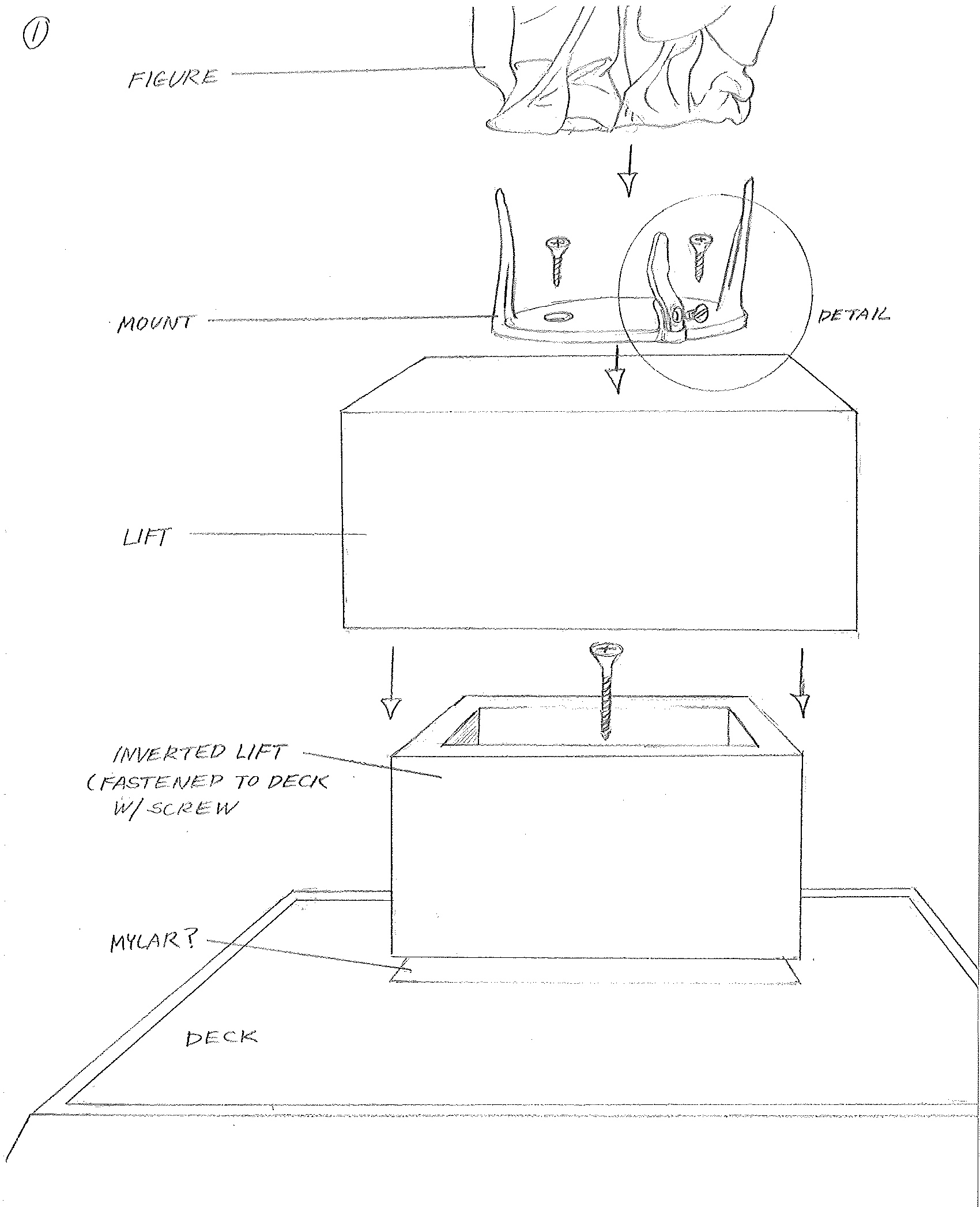

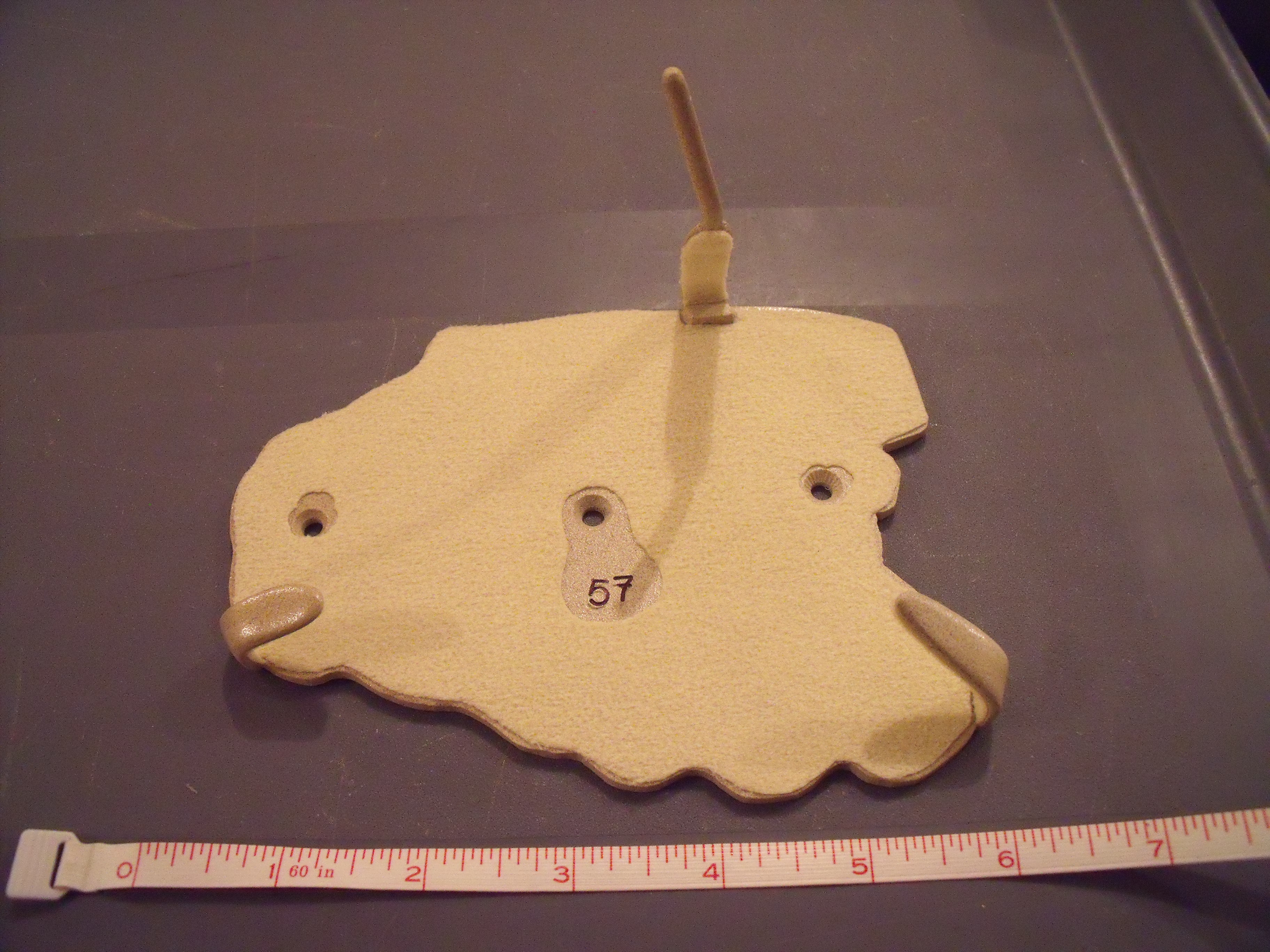

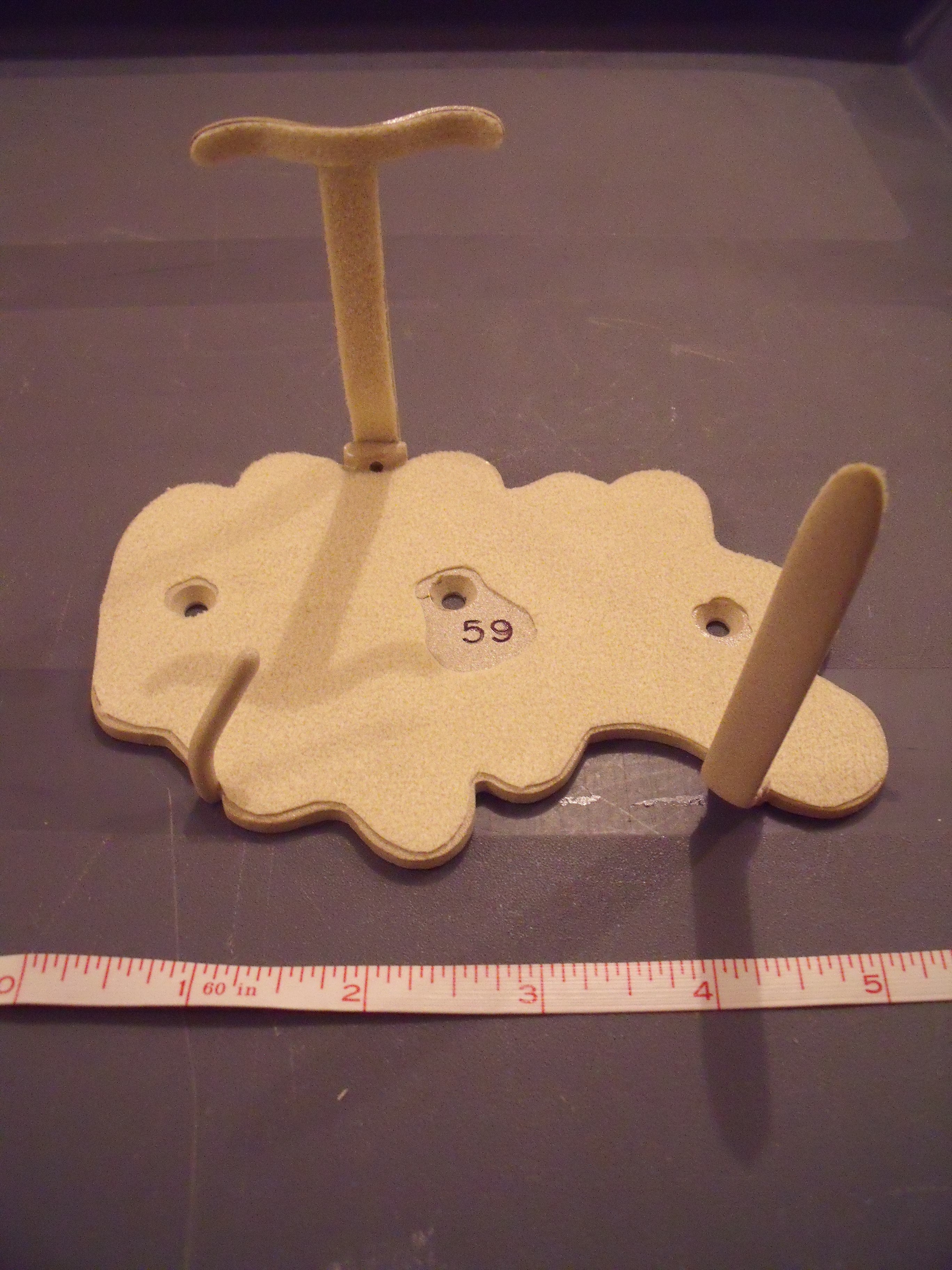

The mounts are crucial to the safety of the sculptures and travel in their own crate with all the supplies needed to make adjustments, touch up paint, replace padding, etc. They were made to fit each individual sculpture, painted to match the color of the alabaster, and padded with conservation felt.

The mounts are crucial to the safety of the sculptures and travel in their own crate with all the supplies needed to make adjustments, touch up paint, replace padding, etc. They were made to fit each individual sculpture, painted to match the color of the alabaster, and padded with conservation felt.