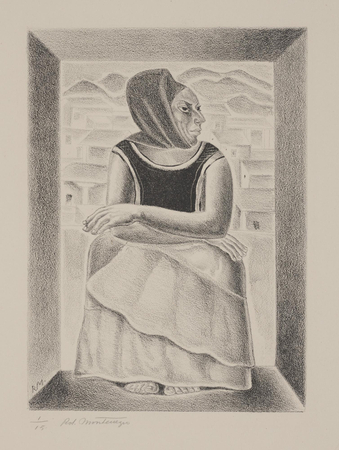

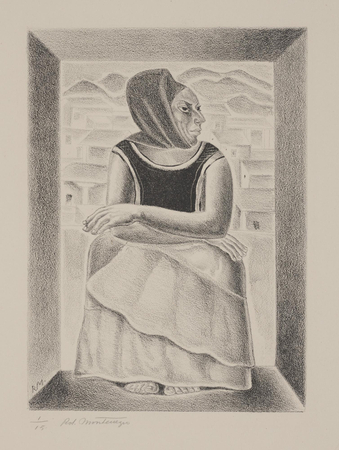

Last week the exhibition México 1900-1950 opened to big crowds, but it is just the most recent DMA exhibition to focus on the art and artists of Mexico. The first known exhibition to feature Mexican art was a solo exhibition in February 1933 of paintings and drawings by Roberto Montenegro. Work by Montenegro is included in the current exhibition and the DMA’s permanent collection.

Roberto (Nervo) Montenegro, Mexican Woman (Tehuana), n.d., lithograph, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Dallas Print Society in memory of Edwin B. Hopkins, 1941.5

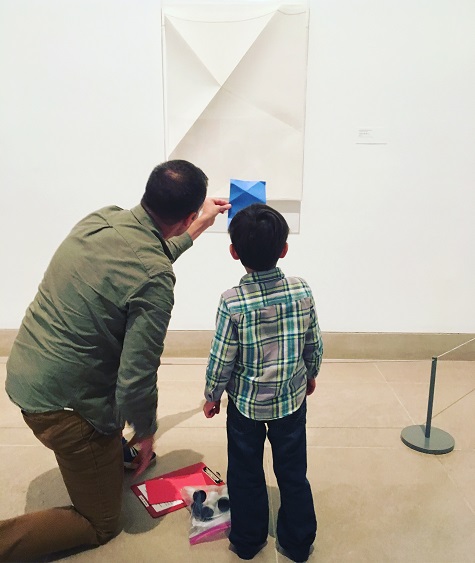

Over the 114-year history of the DMA, with the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts (1957-1963) exhibition history included, 38 known exhibitions (including México 1900-1950) have featured Mexican art and artists, ranging from ancient and pre-Columbian to modern and contemporary. Of the 38, almost half included work by Mexican modernists who also have pieces in the current exhibition. The DMA held solo and group exhibitions for artists Carlos Merida, Roberto Montenegro, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Rufino Tamayo, Gunther Gerzso, Leonora Carrington, and Jose Posada, as well as numerous survey shows of work by Mexican modernists.

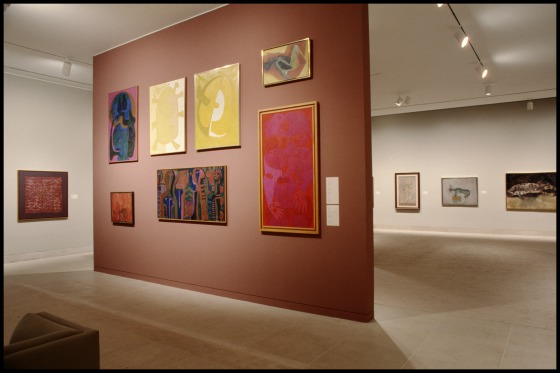

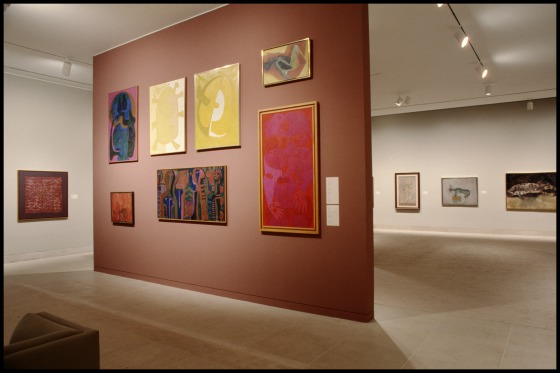

One of the largest exhibitions of the work of Mexican modernists was Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988.

Installation of Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988

Installation of Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988

Like México 1900-1950, Images of Mexico was so large, that it needed to be installed in multiple galleries throughout the building. The main portion of the exhibition was located in the Level 2 European and American Galleries, with additional works in the Barrel Vault, Concourse, Focus I Gallery and the Print and Textile Gallery (now Focus II gallery).

Installation of Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988 in the Barrel Vault

Installation of Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988; Concourse

Installation of Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988 in Focus Gallery I

Installation of Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988 in Focus Gallery II

At least two works in México 1900-1950 are making their second visit to Dallas. Both Olga Costa’s La vendedora de frutas, 1951, and Saturnino Herrán’s Nuestros dioses, 1918, were part of Images of Mexico.

Installation of Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988

Installation of Images of Mexico: The Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art, August 28-October 30, 1988

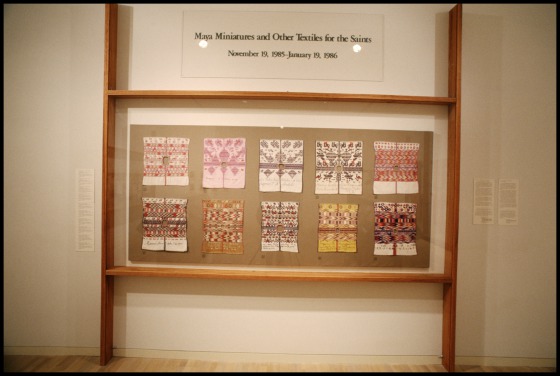

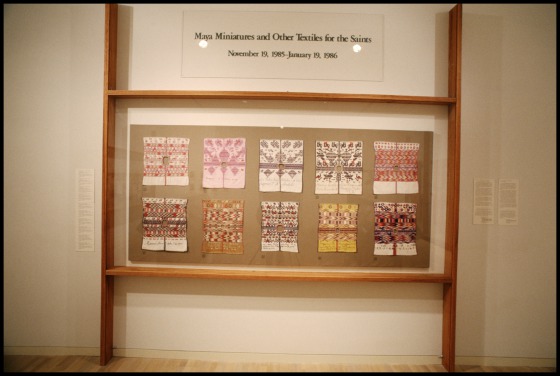

Another primary feature of the México 1900-1950 exhibition is that it includes exhibition text and labels in both English and Spanish. The first DMA exhibition to include labels in English and Spanish was Maya Miniatures and Other Textiles for the Saints, November 19, 1985-January 19, 1986. The exhibition displayed Maya textiles from Guatemala.

Installation of Maya Miniatures and Other Textiles for the Saints, November 19, 1985-January 19, 1986

Installation of Maya Miniatures and Other Textiles for the Saints, November 19, 1985-January 19, 1986

Hillary Bober is the Archivist at the Dallas Museum of Art.