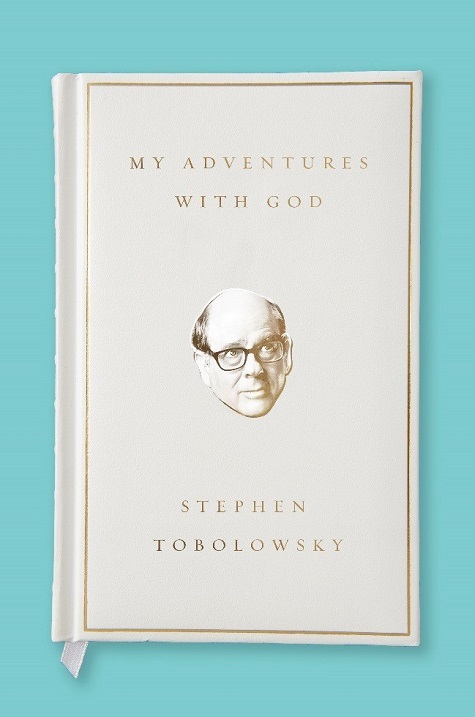

On April 18, Stephen Tobolowsky will return to the DMA Arts & Letters Live stage to celebrate the release of his second memoir, My Adventures with God. In preparation for his visit, I had the privilege of interviewing Stephen about his acting turned writing career and some of the things he learned along the way. His answers are insightful, relatable, and as always, humorous. From the aspiring artist to the admiring onlooker, Stephen offers advice, intentionally or not, for anyone interested in advancing his or her own path to success and level of self-awareness. So, what did I glean from our interchange, you might wonder? Well, as a young professional embarking on a long career ahead of me, this interview reminded me that I do not need to have all the answers, That I can trust my instincts, and that, even in times of doubt, I should cling to what gives me strength and a sense of what makes me, me. Below you can read just a snippet of our discussion and get a glimpse into what’s to come on the night of his much anticipated appearance at the DMA:

Sara: In this book, you continually return to Judaism as a kind of grounding force throughout the vicissitudes of your life. Can you speak broadly about how you understand the role of faith, religious or not, factoring into one’s lived experience?

Stephen: This is the question from which all questions come. We like to think that we are fixed quantities that move through time. We are not. We are equations with more than one unknown. I think this fundamental uncertainty about our existence is why we cling to things we feel are certain. Like science. Like art. It’s why people like cats. We are certain of their uncertainness.

The only protections we have from false prophets and the despair that grips us all at one time or another is beauty and in embracing a good philosophy. Judaism provides both.

We live in an age that popularly views religion as primitive and elevates science. I like science, even when it is wrong. I find the pursuit of answers inspirational. But for my money, I don’t care how smart Steven Hawking is or how interesting a black hole may be, if he doesn’t understand the Holiness code of Leviticus, not to curse the deaf nor put an obstacle before the blind, it doesn’t add up to much.

Judaism is a layer cake built over thousands of years. The different layers reflect that age’s relationship to truth. In some ages, it was popular to think that truth can be known. You end up with the Ten Commandments. In other ages, it was popular to think the truth was hidden. You end up with mystical works like the Zohar and the Midrash. There are very few creations of man that have existed through so many conflicting times and have survived so many hardships. The wisdom embodied in Judaism has endured. The philosophy in a nutshell? From Hillel over two thousand years ago: “What is hateful to you do not do unto your fellow man. The rest is commentary. Go and study.”

To read the entire interview, you can visit Stephen’s website, where he posted the exchange in two parts: Part I and Part II. The Museum is excited to welcome Stephen back to DMA Arts & Letters Live, so go grab a copy of My Adventures with God in the DMA Store and join us for an evening full of inquisitive minds, entertaining anecdotes, and rip-roaring laughter.

Sara Beth Greenberg is the McDermott Graduate Intern for Adult Programming and Arts & Letters Live at the DMA.