Kevin W. Tucker is the Museum’s Margot B. Perot Curator of Decorative Arts and Design. He joined the Museum in the summer of 2003 and has curated acclaimed exhibitions such as Gustav Stickley and the American Arts & Crafts Movement and The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk. Take a peek inside Kevin’s DMA office:

Posts Tagged 'Decorative Arts'

Open Office: Decorative Arts and Design

Published June 10, 2013 Behind-the-Scenes , Decorative Art and Design , Staff 1 CommentTags: Dallas Museum of Art, Decorative Arts, DMA

21 Years of Silver Supper

Published March 4, 2013 Behind-the-Scenes , Collections , Curatorial , Decorative Art and Design , Special Events ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, Decorative Arts, DMA, Silver, Silver Supper

This past Friday was the 21st anniversary of Silver Supper, an annual event that celebrates the DMA’s outstanding holdings of American decorative arts and silver. This year’s Silver Supper highlighted thirty-two works from the DMA’s decorative arts and design collection. For more information on the annual event, visit the DMA’s website.

Soup’s On

Published February 27, 2013 Collections , Curatorial , Decorative Art and Design ClosedTags: Cindy Sherman, Dallas Museum of Art, Decorative Arts, DMA, Louis Comfort Tiffany

In a museum the size of the DMA, it’s hard to keep track of isolated changes over 370,000 square feet. So we are letting you know about three recent additions to the permanent collection that are now on view. I encourage you to visit the Museum and go on a “scavenger hunt” to see how these works add an extra spark to the galleries—remember, general admission is free!

All three of the works fall within the purview of decorative arts and were originally marketed to elite consumers. One is by a well-known figure—the 19th-century design magnate Louis Comfort Tiffany (American, 1848-1933). Fans of contemporary art or those familiar with the DMA’s upcoming exhibitions will recognize the name of photographer Cindy Sherman (American, born 1954). The third designer may be unknown outside of specialist circles, but during his lifetime Archibald Knox (British, 1864-1933) was credited with developing a uniquely British approach to the Art Nouveau movement.

Cindy Sherman, “Madame de Pompadour (née Poisson)” soup tureen with platter, 1990, Ancienne Manufacture Royale de Francem, porcelain with silkscreen transfer and platinum decoration, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA-amfAR Benefit Auction Fund

From March 17 to June 9, the Cindy Sherman exhibition will adorn the walls of the Barrel Vault and Quadrant Galleries, but visitors to the European Galleries can also encounter the contemporary American’s work. Her Madame de Pompadour (née Poisson) soup tureen with platter sits camouflaged with rococo curves and floral embellishments. It creates a provocative disjuncture amid a wall of paintings by Canaletto (Italian, 1697-1768), Jean-Baptiste Oudry (French, 1686-1755), and Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825).

Madame de Pompadour (French, 1721-1764) was the most famous of King Louis XV’s mistresses. She played a critical role in elevating rococo style to the pinnacle of aesthetic taste in mid-18th-century France. In 1756 she commissioned a tureen and platter from the renowned porcelain manufacturer in Limoges. Over two hundred years later, Sherman used the same factory to produce a limited-edition interpretation based on Pompadour’s original design.

Sherman takes on the guise of a historical tastemaker but allows viewers to be in on her joke. Close inspection of the photo-silkscreened portrait (reproduced twice on both the tureen and platter) reveals a pastiche—the theatrical make-up, somewhat ratty shawl, ill-fitting gray wig, and conspicuously faux breasts.

Cindy Sherman, “Madame de Pompadour (née Poisson)” soup tureen with platter, interior, 1990, Ancienne Manufacture Royale de Francem, porcelain with silkscreen transfer and platinum decoration, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA-amfAR Benefit Auction Fund

Museum guests won’t glimpse the tureen’s additional humorous detail because it is hidden on the base of the interior. As a visual pun on Pompadour’s maiden name and extreme wealth, Sherman created a still life of fish (French, poisson) and beaded necklaces.

Tiffany Studios, Vase, c. 1905-1919, earthenware, Dallas Museum of Art, Discretionary Decorative Arts Fund

Several new installations spice up the displays in the North Decorative Arts Gallery. Here you can find the latest addition to the DMA’s collection of works by Tiffany. Placed in a corner case surrounded by other examples of leading art pottery manufacturers, the brilliant hues of this small vase seem to reiterate the impact Tiffany Studios had on American decorative arts.

The iridescent surface shimmers with deep indigos, purples, and teals. The shape conjures images of flower petals or buds. Both traits demonstrate Tiffany’s dual focus on nature and mastering a material’s technical possibilities.

He coined the term “Favrile” in 1893 as an adaptation of the Old English word for “handmade.” The same moniker distinguished the wares of the ceramic workshop when it opened at Tiffany Furnaces (Corona, New York). As seen here, the glazing process allowed for creative expression and experimentation on the surface of an object formed from an existing mold.

Archibald Knox, Liberty and Co., W. H. Haseler & Co., Box (model 652 variant), 1905, Dallas Museum of Art, anonymous gift.

The third object making its DMA debut appears in a case on the east wall of this gallery. It’s hard to miss a lavish box decorated with incised linear patterns and blue-green enamel, and topped by a sizeable opal. On the adjacent platform, a charger with ship motif (1881) and a bench (1900) echo the Celtic stylings seen on Knox’s construction. Taken as a whole, the arrangement illustrates the late 19th-century interest in national identity. Many artists in Europe used the contemporary archeological discoveries of Scandinavian sites as source material for a “Viking Revival” style.

This piece is one of four variants known to exist. Unlike the other, simpler iterations, the model 652 variant features a bulging lid beset with a substantial gem. Within Liberty & Co.’s Cymric line, this would have been one of the costliest items for sale. Thankfully, this and the other works described above can be seen free of charge at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Emily Schiller is the McDermott Graduate Curatorial Intern at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Decorative Dining

Published October 25, 2011 works of art 3 CommentsTags: collections, Decorative Arts, Silver, The Gilded Age, Victorian Dining

Everyone needs to eat, right?

We spend plenty of time thinking about what we are going to have for dinner every day, but how often do you think about the objects that contain, serve or cut your food? In the age of the microwave and the drive-thru, it may seem crazy to think about breaking out your finest silver pieces to serve dinner. To wealthy and upper middle-class Americans during the Victorian era (or more specifially, The Gilded Age) the practice of dining was an art, and fine silver was a key component.

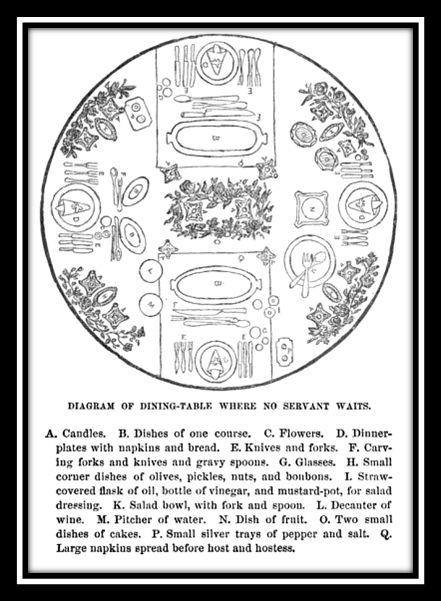

Let’s start with an example of how Mrs. Maria Dewing suggests a proper dinner table should be set in her helpful guide, Beauty in the Household, published in 1882.

Image from Maria Richards Dewing’s Beauty in the Household (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1882), page 72.

As you can see, even a small gathering without servants (gasp!) called for a very specific placement of dishes. It is, then, no surprise that such great care was taken in the appearance of the serving utensils and dishes. Not only was there a specific placement of the pieces, but they were also often decorated and designed in accordance with their function.

Here are a few flatware examples from one of the largest (it totaled about 1,250 pieces) and grandest (it was made from a half ton of silver) dinner and dessert service that Tiffany & Co. made in the 1870s:

Egg Spoons

Oyster forks

Grape scissors

Asparagus tongs

Salt spoons

Marrow spoons

Melon knives

Berry spoons

We feel stressed today if we use the wrong fork for our salad — can you imagine being forced to choose between an egg spoon and a berry spoon? Well-bred Victorians would have known the difference.

Luckily, if they had a moment of doubt, the silver designers often provided hints as to how the item may be used. The DMA’s Decorative Arts collection has some wonderful examples of these types of silverware.

Sometimes, specific foods were incorporated into the designs.

Others may subtly hint at the type of food for which they were used.

On the other hand, designers did not always give such helpful hints. Instead, they creatively designed an item using influences from non-food related objects.

- Both of the items below have very specific uses; what do you think they are? Leave your ideas in a comment and I will provide the answers in the comment section next week!

-

Left: Gorham Manufacturing Company, c.1880, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Dale Bennett Right: B.D. Beiderhase & Co., 1872, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Dale Bennett

While most Victorian families may not have purchased such whimsical silver pieces as these, the widespread market for silver gave designers the freedom to create wonderfully dynamic works of art that we can marvel over today at the DMA.

- Bon Appétit!

McDermott Intern for Gallery Teaching

Form/Unformed: Goldilocks and the Chairs

Published March 31, 2011 works of art 2 CommentsTags: campbell, chairs, Decorative Arts, Design, exhibitions, form, gehry, judd, panton, unformed

This past December, the Tower Gallery on the fourth floor of the Museum became home to Form/Unformed: Design from 1960 to the Present. This exhibition showcases over thirty works drawn largely from the Museum’s collections and reveals the ever-evolving formal aesthetics and ideas that have influenced design of the last fifty years. Featuring everything from room dividers to candlesticks, the space pays homage to design powerhouses such as Verner Panton, Frank Gehry, Donald Judd, and Louise Campbell. Though a broad array of objects appear in the exhibition, one cannot help but notice an overwhelming number of chairs!

[slideshow]

Like Goldilocks entering the three bears’ home, we are presented with a selection of chairs ranging across all shapes and sizes. As our exhibitions currently have a heavy empahsis on design, with Gustav Stickley and the American Arts & Crafts Movement and Line and Form: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Wasmuth Portfolio, the Education staff began brainstorming how our society describes furniture and what appeals to us about various pieces. In an effort to find the chair that is JUST RIGHT for you, here are some of the descriptors that may appear on any one of our wish lists for the perfect chair: organic, innovative, angular, minimal, sturdy, plush, colorful, weird, comfy, casual, simple, unique, futuristic, traditional, embellished, symmetrical, asymmetrical, functional, imaginative, elegant, versatile, compact, playful, practical, nostalgic, modern….As you can see, there are as many different ways to describe a chair as opinions on what qualities make the perfect chair!

What words describe your ideal chair? Share with us in the comments section!

Form/Unformed: Design from 1960 to the Present will run through January of 2012 and is free with general admission to the Museum.

Ashley Bruckbauer

McDermott Intern for Programs and Resources for Teachers

"Exotic" Mexican Objects at the DMA and Crow Collection

Published November 5, 2010 Community Connection , Friday Photos , works of art ClosedTags: appropriation art, Asian influence, bicentennial, Black Current, chinoiserie, Crow Collection of Asian Art, Decorative Arts, japonisme, Mexico, Mexico 200, posada, Tierra y Gente

In commemoration of the 2010 bicentennial of Mexico’s independence from Spain, many Dallas-area institutions have hosted events or created exhibitions related to Mexico’s past, present, and future. In addition to highlighting Mexican and Spanish colonial works in the Museum’s fourth floor galleries, the DMA currently has two special exhibitions celebrating Mexico’s 200th anniversary: Jose Guadalupe Posada: The Birth of Mexican Modernism and Tierra y Gente: Modern Mexican Works on Paper.

For me, one of the most intriguing objects in these galleries is an eccentric folding screen from colonial Mexico. This screen is elaborately painted and gilded in the European decorative tradition, but its central vignettes are drawn from a Flemish book of moralizing tales. Additionally, the ornate borders of the screen contain Japanese and Chinese-inspired motifs popular in European Rococo. This object connects with a recently opened exhibition, Black Current: Mexican Responses to Japanese Art, 17th-19th Centuries, also in celebration of Mexico’s bicentennial, at the Crow Collection of Asian Art.

[slideshow]

*Photography by George Ramirez

This exhibition includes Mexican-made objects, such as folding screens and rolled paintings, that were greatly informed by trade via the The Black Current. This marine trade route, established in the 16th century, ran eastbound from Manila to Acapulco, bringing goods such as decorative arts, silk, and spices to Mexico. Approximately 500 Pacific crossings were made along the dark river in the sea, feeding the growing market for luxury commodities in Mexico and generating Asian demand for American resources such as silver. These exchanges led to an artistic interchange that left lasting impressions on Mexican artists.

Cosmopolitan, Mexican-made objects, such as those in Black Current and the DMA Screen, reference their Asian precursors through the inclusion of Asian-inspired motifs, use of laquer, inlay and shells, and format of the folding screen and scrolls mounted on rollers. Additionally, they serve as visual documentation of ambitious exchanges between spatially disparate cultures.

Ashley Bruckbauer

Programs and Resources for Teachers Intern