Pablo Picasso’s first financial success came in spring 1906, when he sold the entire inventory of his studio to art dealer Ambroise Vollard for the then large sum of 2,000 francs. This allowed him and his partner, Fernande Olivier, to travel to Barcelona and from there to the Pyrenean village of Gósol. In Spain, Picasso was a different person, Olivier remembered: “[A]s soon as he returned to his native Spain, and especially to its countryside, he was perfused with its calm and serenity. This made his works lighter, airier, less agonized.”1 It is not surprising then that in the almost three months the couple spent in Gósol, Picasso produced more than 300 paintings, drawings, and sculptures with Olivier as his main model. A significant change in his style announced itself during these months, influenced in part by the spare landscape and the region’s unique colors, but also by two exhibitions he had recently seen: the Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres retrospective at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, and a display of Iberian art at the Louvre from recent excavations in Andalusia.

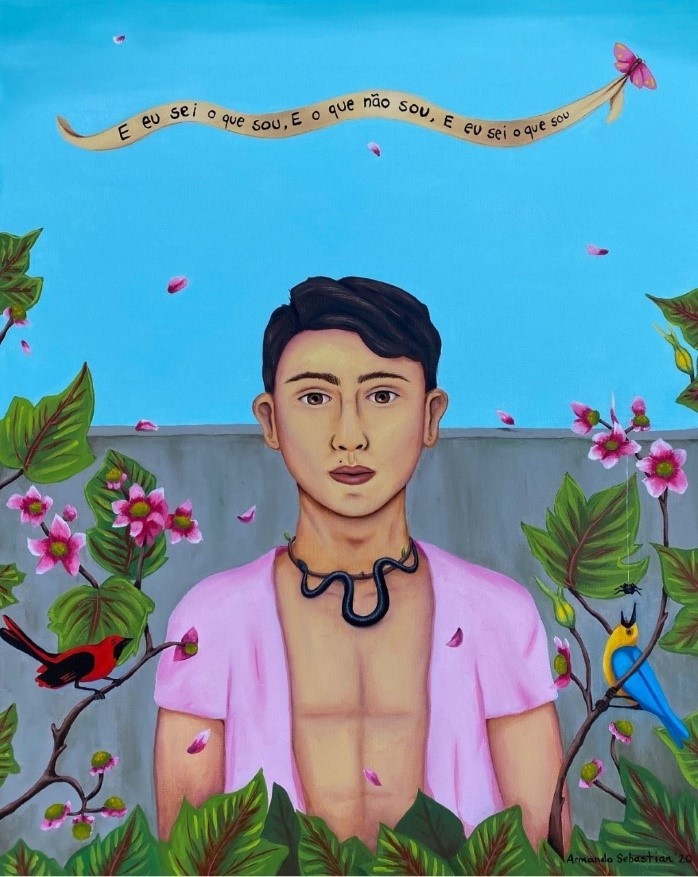

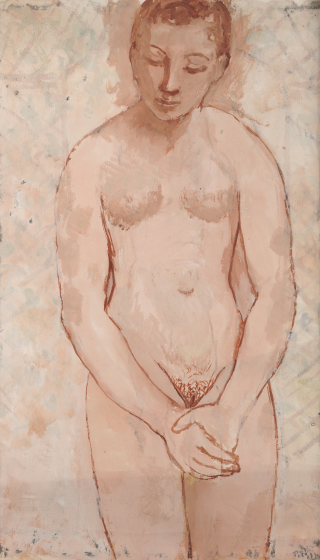

A diamond pattern and the contours of a figure bleed through the thin paint of the pale pink background in Nude with Folded Hands. Only Olivier’s own ocher outlines set her apart from the nondescript, empty environment in which she is standing, giving the painting the effect of a bas-relief. Her voluptuous body seems awkwardly twisted at the waist and shoulders, her head is slightly bent down, and her almond-shaped eyes are closed. In its rigidity, the face evokes Iberian art, as well as a sculpture bust of Olivier, Head of a Woman, that Picasso made in the same year. Standing in front of her beholder, she is timidly folding her hands below her pudenda; however, her modesty is a false one, her hands revealing more than they hide, guiding the viewers gaze. Olivier often posed in the nude for Picasso, and while the young artist frequently made small drawings and caricatures of his sexual escapades, the studies and paintings of Olivier from 1906 stand out through their intimate eroticism, absent in his earlier works and in the following years.

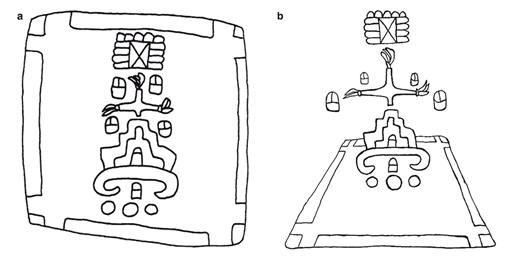

Bust, probably painted in the winter of 1907–08, looks fundamentally different from Nude with Folded Hands, and much had happened in the meantime. In spring or summer 1907, Picasso visited the Indigenous art and culture collection at the Musée du Trocadéro in Paris, which, though dusty and deserted, opened his eyes to a new influence: art from outside the Western canon, originating from European colonies in Africa and Oceania, leading him to finish his monumental painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907, MoMA). Finally, at the Salon d’Automne, he saw the retrospective dedicated to Paul Cézanne. These exhibitions greatly influenced Picasso’s artistic development and his quest for an escape from the confines of illusionistic art, established during the Renaissance. Picasso further explored the pictorial means of simplification, thus the muscular woman in Bust, lifting her arms above her head, pulling her hair into a bun, is reduced to outlines and shading that was achieved through isolated application of color and expressive brushstrokes, rather than through the traditional method of gradients from white to black. Her face, devoid of emotion, echoes the masks Picasso saw at the Trocadéro, which might have looked like the Je face mask from the Yaure peoples. The fragmented body is reduced to basic geometric shapes, with the contours opening so that the background and the foreground merged, as Picasso had observed in Cézanne’s work.

The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., bequest of Mrs. Eugene McDermott, 2019.67.6.McD

Despite being celebrated as an inventor, Picasso never worked in an artistic vacuum. Trying to find a new language from 1906 onward, he was especially receptive to influences from outside the traditional Western canon, which makes these works compelling, even for the present-day beholder.

[1] Fernande Olivier, Picasso und seine Freunde. Erinnerungen aus den Jahren 1905-1913, 1989, p. X. Translated from German by the author.

Christine Burger, Curatorial Research Assistant for European Art