It’s always fascinating to see which objects in the DMA’s collection artists are drawn to because it can be a window into what is on their mind and how they think about their own work. For the last three years, the DMA has partnered with the local arts nonprofit Arttitude to celebrate the work of LGBTQ+ visual and performing artists in Dallas through programs like State of the Arts and our annual Pride Block Party. Since we are unable to tour the galleries with local artists for Pride Month this year, we reached out to two artists who exhibited in Arttitude’s recent MariconX show and invited them to find and respond to an object in the DMA’s collection that resonates with their own work. Here is what they had to say:

Armando Sebastián is a Dallas-based painter whose work draws on Mexican folk art and his own life experiences to explore themes of gender and identity. Sebastián describes his style as akin to magical realism, and he is particularly interested in referencing the traditional Mexican folk art genre of ex voto paintings depicting divine interventions into human misfortunes.

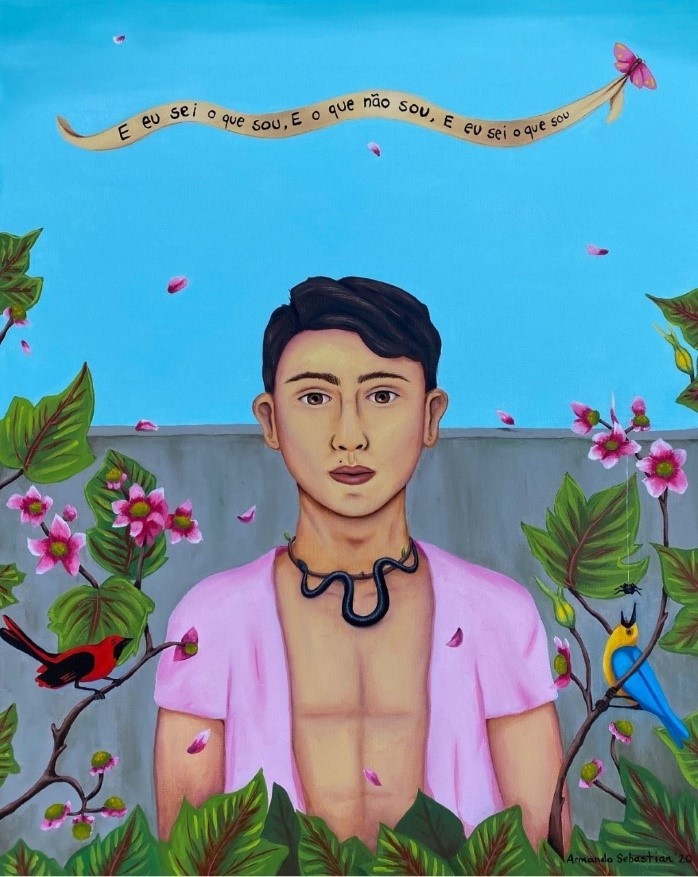

Here are a few recent paintings from Armando Sebastián. You can see more of his work on his website and on Instagram.

Images: Armando Sebastián, Los Amados / Live in Harmony, 2020; I know who I am, 2020; The Dreamers, 2019

Sebastián chose the 18th-century painting Christ as Savior of the World (Salvator Mundi), reflecting:

“The angels above are conspiring to the master plan on earth. The trinity holds flaming hearts, perhaps the interpretation of humankind. On the ground you see the depiction of evil, a beast eating a fruit. The ladder to the heavens is full of obstacles that makes it impossible for anyone to climb. I personally appreciate narrative in art, the possibility to convey complex ideas and hidden meanings through your work.”

Olivia Peregrino is a Dallas-based photographer working in portraiture and documentary photography. She began her career as a photojournalist, and her work has expanded to include uplifting portraits of women and Latinx LGBTQ+ communities, event photography, and documentary filmmaking.

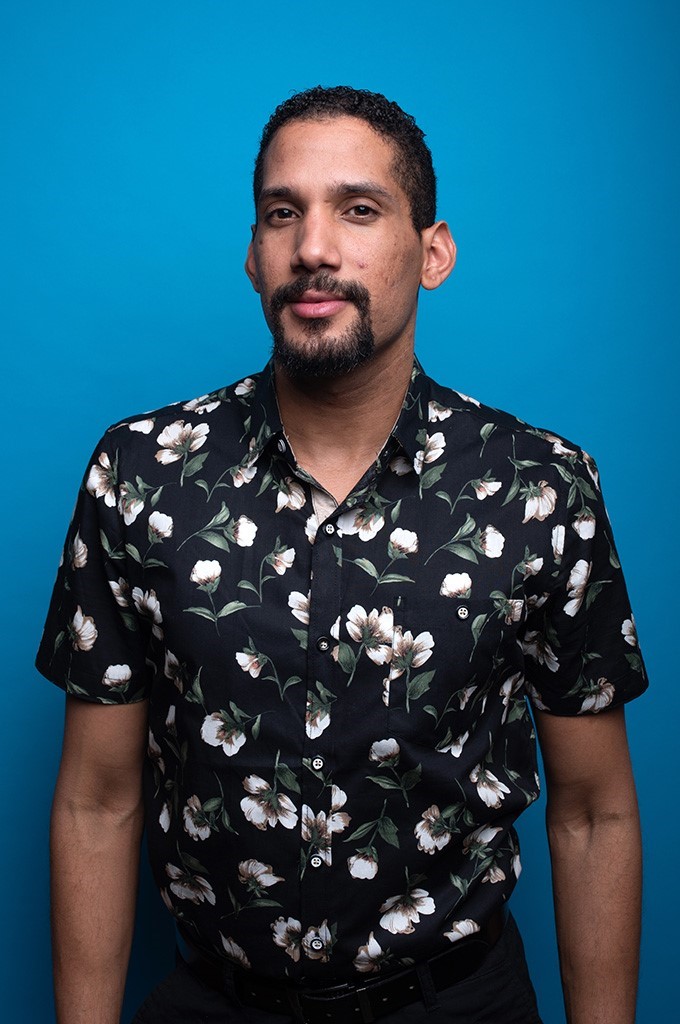

Here are a few recent photographs by Olivia Peregrino. To see more of her work, follow her on Instagram or visit her website.

This slideshow contains nudity.

Images: Olivia Peregrino, Omar, El Salvador, LGBT Immigrant, ongoing project, 2020; Rafael, Colombia, LGBT Immigrant, ongoing project, 2020; Wandel, Dominican Republic, LGBT Immigrant, ongoing project, 2020; Melissa, Natural Bodies, 2018

Olivia chose Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1981 photograph Ajitto, saying the following:

“Robert Mapplethorpe is one of my favorite artists for the beauty of his portraits and his mastery of light and composition. Ajitto’s portrait perfectly reflects Mapplethorpe’s recurring obsessions in his photographs. The representation of the human body through the female and male nude is a theme that I, as an artist, also seek to show in my portraits, but from a feminine and contemporary perspective.”