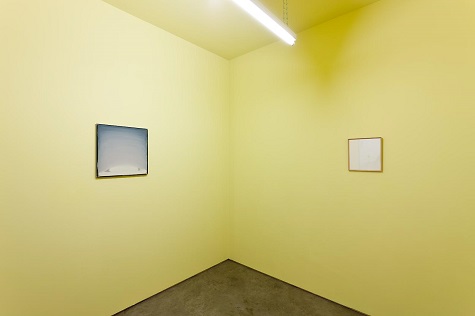

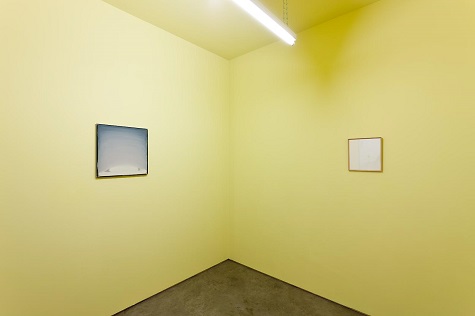

William McKeown, The Dayroom, 2004-10, a room, a painting, and a drawing, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA/amfAR Benefit Auction Fund, 2015.44.a-c, © William McKeown

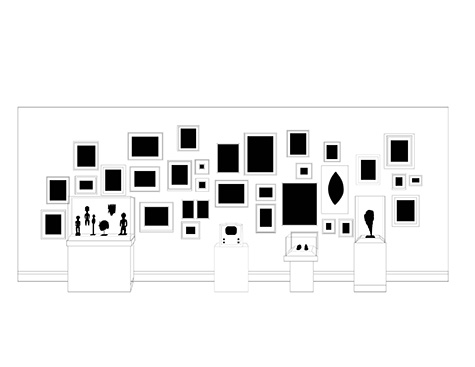

In a quiet corner of the DMA’s Barrel Vault, a recent acquisition to our contemporary collection sits inconspicuously in the Hanley Quadrant Gallery. Installed in March as part of Passages in Modern Art: 1946-1996, William McKeown’s The Dayroom references spaces found in institutions associated with illness and aging—hospitals, retirement centers, convalescent homes. Via artificial lighting, washed-out yellow walls, and a confining boxlike structure, McKeown attempts to mimic the disquieting artifice that pervades these rooms, which are often decorated with brightly colored wallpaper and works of art that attempt to cheer up an otherwise morbid space.

The installation takes the form of a room that initially appears to be little more than a framework of exposed wooden struts, scaffolding, and drywall; however, a window built into the side of the structure frames a direct sightline to a painting hung within the cube, inviting the viewer to enter the interior of the installation.

Pale yellow walls and cold fluorescent light welcome the viewer into the unsettling interior of The Dayroom. The sickly colored walls illuminated by the harsh sodium light elicit feelings of claustrophobia. The window looks out onto darkness, serving as a reminder of one’s containment and separation from the outside world. Working in tandem, these structural components form a space that situates the viewer in a position of captivity and powerlessness. After all, dayroom occupants are rarely there by choice.

McKeown’s vision, however, is not one of hopelessness. Hung on the interior walls are a painting and a drawing, both of which function metaphorically as breaths of fresh air within an otherwise suffocating setting.

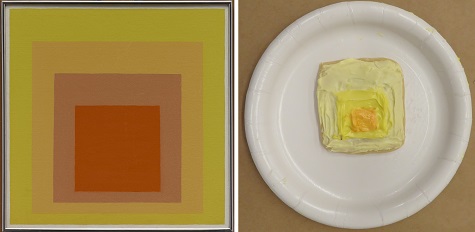

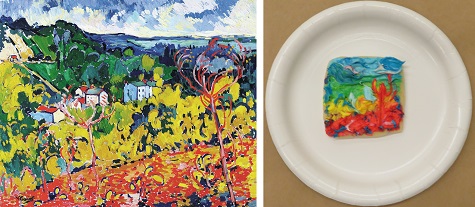

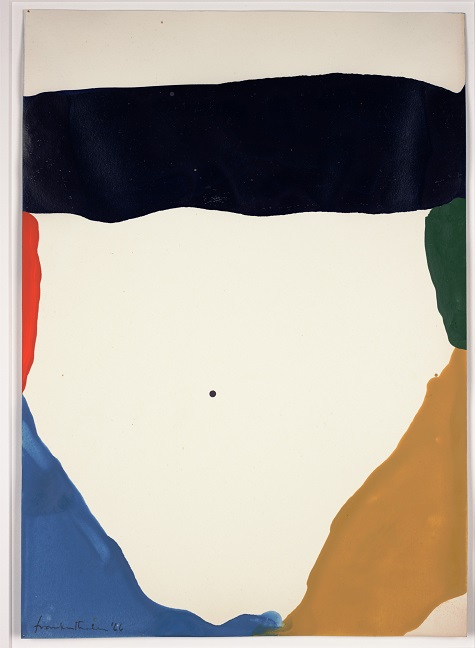

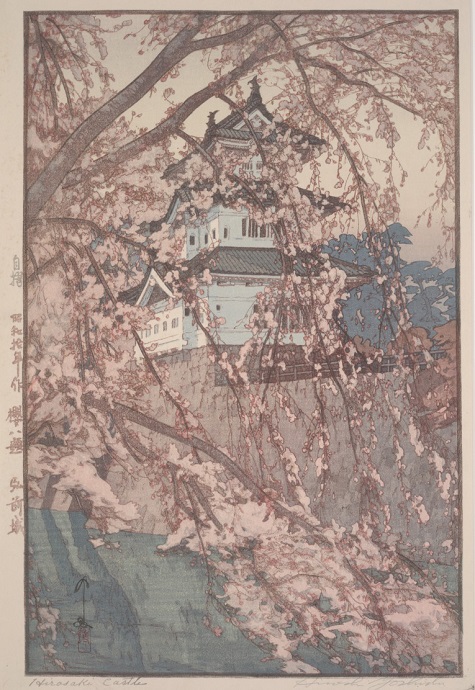

Left: William McKeown, Untitled, 2004-10, oil on linen, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA/amfAR Benefit Auction Fund, 2015.44.a-c. Right: William McKeown, Open drawing – Narrow Lane Primrose #2, 2005, coloring pencil on paper, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA/amfAR Benefit Auction Fund, 2015.44.a-c. Both works © William McKeown.

Untitled is an oil on linen painting that represents a moment of soft early morning light experienced by McKeown. While the painting may appear to be a direct rendering of a sky, McKeown insisted that the work is, in fact, a hybrid image—one that melds an objective documentation of light with his own subjective, emotional response to it.

Installed on an adjacent wall, Open drawing – Narrow Lane Primrose #2 is a colored pencil drawing of a primrose, a flower found in the artist’s hometown in Tyrone County, Northern Ireland. Rendered so faintly that the paper initially appears to be blank, the yellow primrose is set against a stark white background, seeming to sprout, against all odds, out of nothing.

Both works encourage a heightened sensitivity to quiet, often unnoticed natural phenomena—the softness of daylight in early morning, a flower that reminds one of home—all the while providing moments of tranquility and hope within the oppressive interior space of the room. For McKeown, a work of art is meant to elicit a sense of belonging in the viewer. Best explained by the artist, he once said during a lecture at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, “When I paint a painting that has no image or a drawing of an open flower, I try to focus on a moment of inspiration, a moment of not feeling separate from nature or from self, a moment of the awareness of the perception of life, of perfection, of being at home in this world.”

The structure of The Dayroom frames McKeown’s painting and drawing as liberating objects, suggesting that works of art can, even if only for a moment, transport the viewer to a better, imagined state—one marked by hope, openness, and the warm feeling of belonging.

The Dayroom will be on view at the DMA through March 2017.

Nolan Jimbo is the Temporary Project Coordinator, Curatorial, at the DMA.