Earlier this month, the DMA’s exhibition The Power of Gold: Asante Royal Regalia from Ghana opened to the public. What you may not know is that the entire exhibition of more than 250 objects was inspired by a few works from the DMA’s collection. The DMA Member Magazine, Artifacts, explored two of these objects in the Winter 2018 issue. Discover more about the inspiration behind the exhibition and the history of these beautiful pieces:

In 2014, two finely crafted gold artworks joined the Dallas Museum of Art’s holdings of West African regalia. The cast gold spider and T-shaped bead arrived in an elegant velvet-lined display box bearing an inscription with the following information: the items came from the Asante kingdom, were once owned by the kings, and left their original home in 1883.

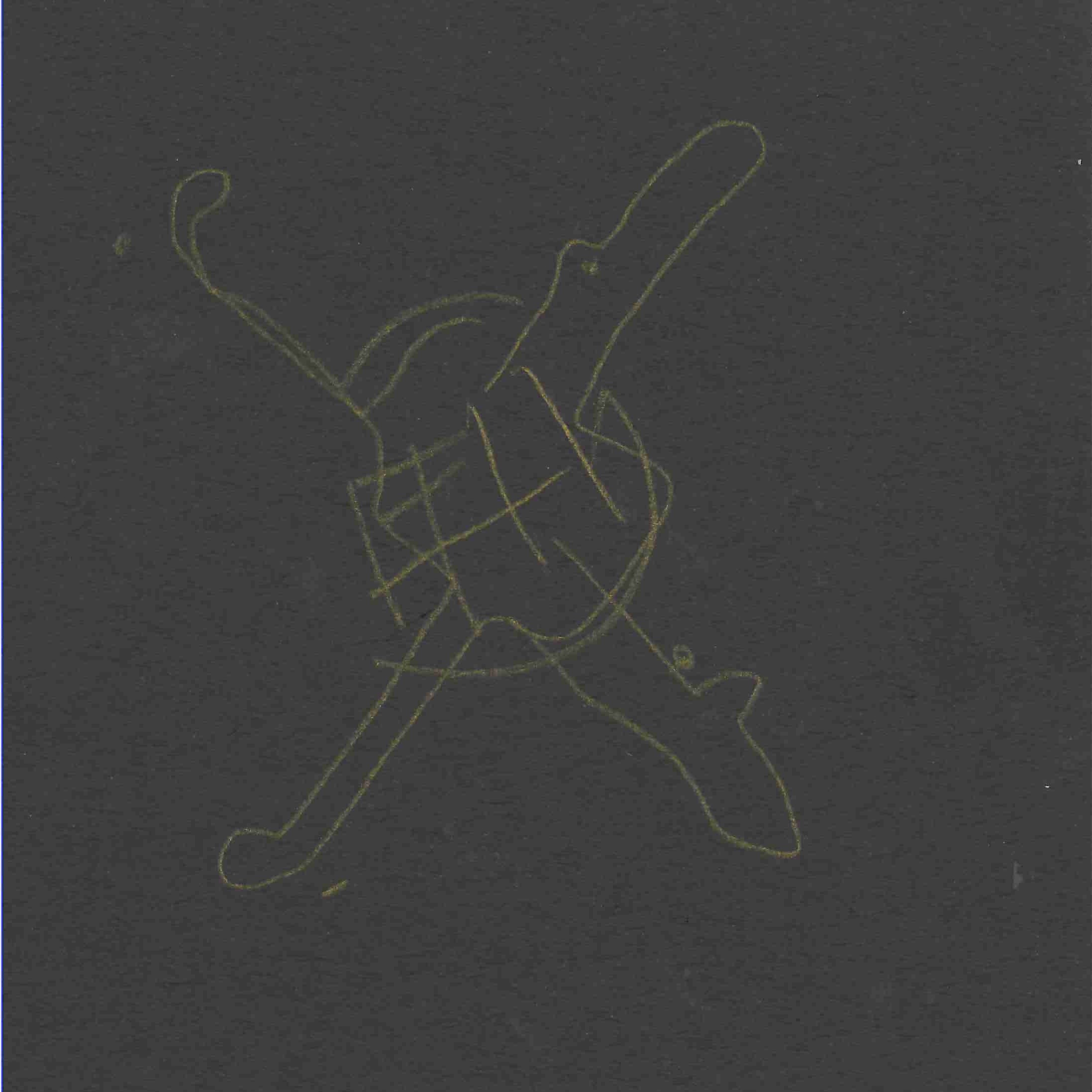

Sword ornament in the form of a spider, Ghana, Asante peoples, late 19th century, gold-copper-silver alloy, Dallas Museum of Art, McDermott African Art Acquisition Fund, 2014.26.1

Dr. Roslyn A. Walker, Senior Curator of the Arts of Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific, and The Margaret McDermott Curator of African Art at the DMA, began a multi-year investigation into the works’ journey from the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) to Texas. This research inspired The Power of Gold: Asante Royal Regalia from Ghana, the first exhibition to focus on Asante royal regalia in over three decades. The Cree family were previous owners of the objects, and in their oral history detailing the objects’ relocation from Africa to England they mention a man named Robert L. Brandon Kirby. Who was Brandon Kirby and how did he come to own these ornate examples of gold craftsmanship? These questions drove Walker to dig through British Parliamentary Papers, correspond with international archivists and scholars, and trace census records throughout the US and Europe. Born in Australia in 1852 as Robert Low Kirby, and later recorded under the surname Brandon Kirby and then Brandon-Kirby, he traveled in 1881 to the British colony, where he served in the Gold Coast Constabulary, a police force. He earned the respect of the British governor of the Gold Coast, Sir Samuel Rowe, and during a mission in 1884 he was tasked with delivering letters from Sir Samuel to the kingdom’s various paramount chiefs regarding the pending selection of an heir to the Golden Stool (throne).

Walker’s reconstructed narrative identifies this tour through the Asante kingdom as the context for Brandon Kirby’s possession of the cast gold spider and T-shaped bead, which were probably bestowed upon him by Prince Agyeman Kofi, later known as Asantahene (king) Kwaku Dua II.

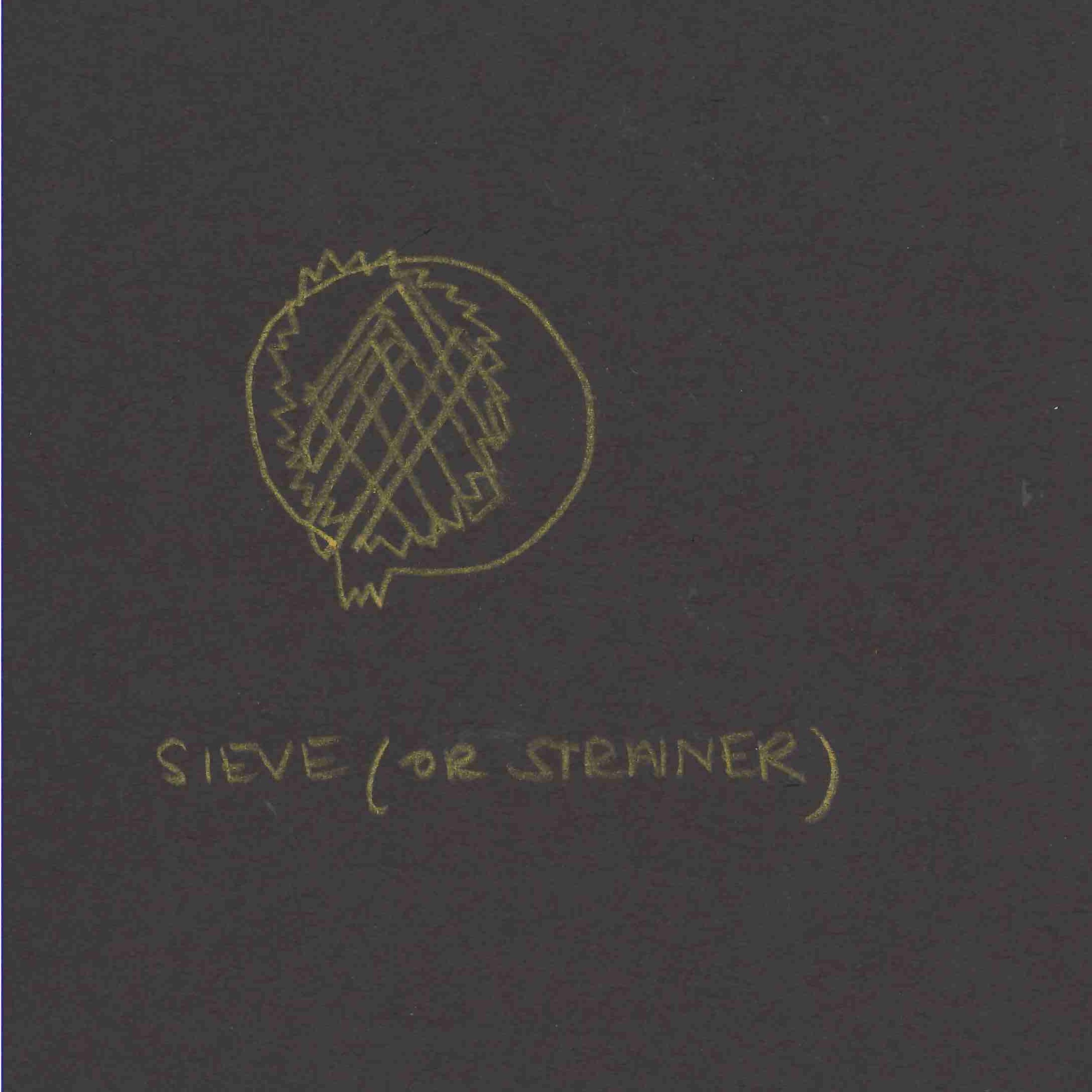

Pendant, Ghana, Asante peoples, late 19th century, gold-copper-silver alloy, Dallas Museum of Art, McDermott African Art Acquisition Fund, 2014.26.2

The following year, Brandon Kirby partnered with James Cree (d. 1891), a wealthy Scotsman, to buy cattle ranches in the Territory of New Mexico, thus the Asante spider and bead arrived in the US. According to Cree family lore, Brandon Kirby’s dramatic departure from New Mexico forced him to travel light, leaving behind his mementos of his time in the Gold Coast.

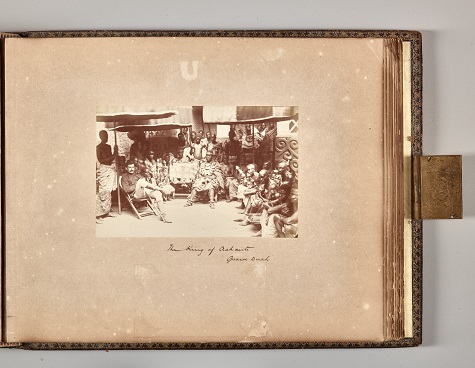

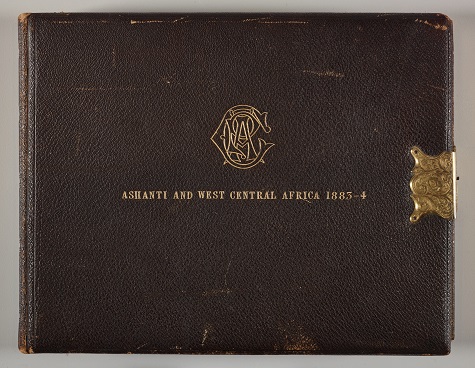

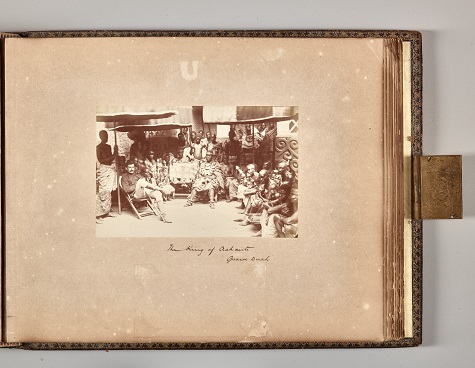

The intricate castings were then passed through generations of the Cree family, landing in Austin, Texas. From there, it was only a few hundred miles and years of research before their reintroduction at the DMA in The Power of Gold. A final historical resource soon joined the spider and bead at the DMA and recently entered the Museum’s collection—an album of photographs by Frederick Grant dated 1883–84 and featuring Brandon Kirby in Kumasi, the capital of the Asante kingdom.

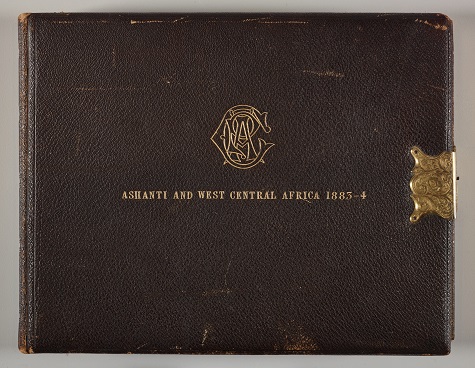

Frederick Grant, Ashanti and West Central Africa, 1883-4 (cover), 1883–84, leather, copper alloy, and paper, Dallas Museum of Art, African Collection Fund, 2017.12

Frederick Grant, Ashanti and West Central Africa, 1883-4 (detail), 1883–84, leather, copper alloy, and paper, Dallas Museum of Art, African Collection Fund, 2017.12

Find out more about Brandon Kirby and the golden spider in the beautifully illustrated exhibition catalogue that accompanies the exhibition.

Dr. Emily Schiller is the Head of Interpretation at the DMA.