After recently acquiring a piece of Caddo pottery by Chase Kahwinhut Earles, we reached out to the artist at his home in Oklahoma to hear about his practice and process. Listen to his introductory message and read his Q&A conversation with Dr. Michelle Rich,The Ellen and Harry S. Parker III Assistant Curator of the Arts of the Americas at the DMA.

Chase: Kuha-ahat [Hello]. Kumbahkeehah Kahwinhut [My name is Kahwinhut]. Hello my name is Chase Kahwinhut Earles, and I’m a member of the Caddo Nation. I make traditional pottery and also contemporary pieces incorporating modern interpretations of our culture.

Michelle: Can you describe the process by which you make your pottery?

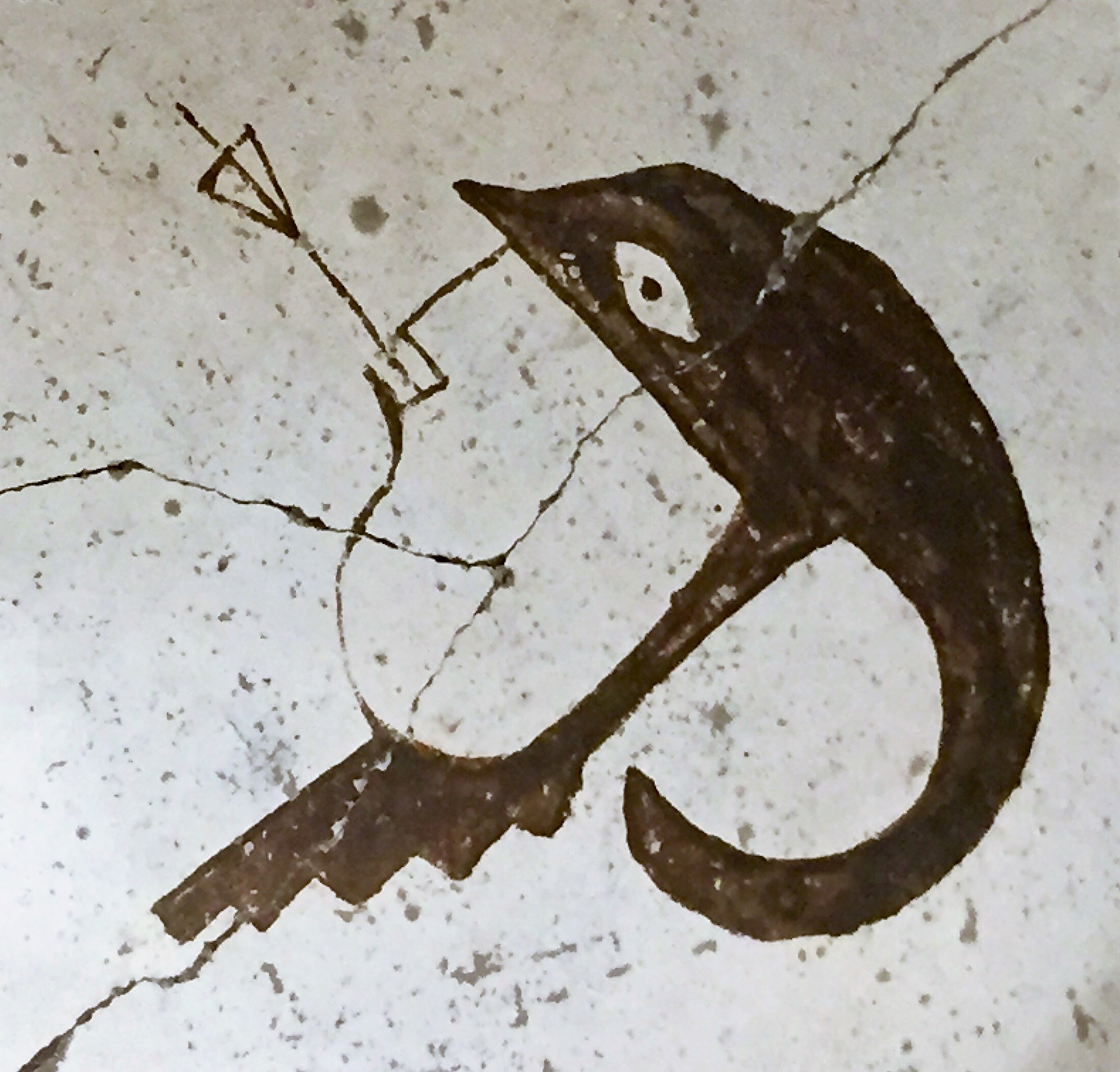

Chase: I make pottery the ancestral, or traditional, Caddo way. I dig the clay myself from the banks of different rivers, mostly the Red River between Texas and Oklahoma. I process it to dry it and break it down into usable material. I collect and crush freshwater mussel shell to mix with the clay as a temper, which helps strengthen it so the vessels survive through the pit-firing process. All of my pieces are hand built using the coil method. I don’t use a wheel. After a piece dries, I burnish it with smooth stones to make it shiny. There’s no glaze. Then I pit fire the vessels. The final step is to engrave the design into the carbonized surface of the pots.

Michelle: Pit firing is very different from kiln firing. Will you talk about that a little bit?

Chase: I fire my pots in a traditional pit fire. This is different than the modern kiln, which slowly heats the pottery until it gets to high temperatures. Our pit firing is started by stacking sticks and lighting an open ground fire. First, we heat the pottery near the fire to drive out moisture, and then they go right into the fire. I’ll add more wood, and the larger fire will get to a high enough temperature to vitrify the clay. You can see the pots start glowing! Sometimes things can go wrong, and if a pot gets overfired it will become fragile or might even spawl or crack. Large pieces, such as the Alligator Gar, can be fired in sections or with multiple fires.

Michelle: What inspired you to make Caddo pottery?

Chase: My parents took us to the Southwest when we were young. I loved and was inspired by the beautiful Pueblo pottery and wanted to make those beautiful pots. And I did learn how, but realized there was something not right about that, and I came to understand the difference between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation. That pointed me in the right direction—to look at my own tribe. I mean, why wouldn’t I have? But I didn’t expect to find anything. Lo and behold, we have one of the biggest pottery traditions in the country, but not many people know about it! Then my purpose was obvious. I dove in, obsessively learning everything about our tribe, our pottery tradition, and our techniques. Jeri Redcorn, a Caddo elder who revived Caddo pottery, helped me get started.

Michelle: The words “contemporary” and “traditional” carry a lot of weight when describing Indigenous arts made in a customary fashion. Where do you situate your work?

Chase: The question of contemporary and traditional is complicated with Native American art, where these words are used to describe the difference between something that’s made in a modern manner or something that’s made exactly how we’ve made things forever. My work up to this point has been primarily trying to save our ancestral and traditional ways of making pottery, so it’s a very ancient style, method, and technique. The present-day definition of “contemporary” is that you’re a living artist. So, in fact, we can be contemporary and traditional at the same time—I’m a living artist producing fine art. But I thought it was important to learn and reestablish our ancestral way in order to have a base to move forward, evolve our work, contribute to Caddo culture, and develop a modern narrative.

Michelle: What does it mean to you to have the DMA acquire your work?

Chase: It means the world to me. When I set out to make pottery and art, specifically our tribal art, it was clear that not many people knew about the Caddo, even though we were once a huge, great society. And no one knew about the pottery, and the tradition kind of got forgotten. Having my work in institutions and museums like this is the ultimate goal—to share our beautiful artistic traditions with people and educate them about our identity, our culture, and our continued presence. So, on the scale of importance, it’s up there at the top!

Also, I can’t thank the DMA enough, especially for this opportunity. It goes a long way to educate people about the importance of Native American artwork in the context of American art. I applaud that effort and am very thankful for it.