When Wendy Reves donated a massive collection of over 1,400 objects to the DMA in 1985, it was already known that a few large furniture objects, like the dining table, originally belonged to Coco Chanel. Recently, we began a new quest to see what other objects might have belonged to Mlle Chanel that are currently in the DMA’s collection. To do so, we looked at old photographs from the 1930s and 40s, when the designer lived at Villa La Pausa, in southern France, and tried to match furniture in those photos to what we have today in the Reves Collection. When we found matches, we knew that the objects were left behind by Coco Chanel when she sold La Pausa to Emery and Wendy Reves in the early 1950s. Here are a few examples so you can go see for yourself.

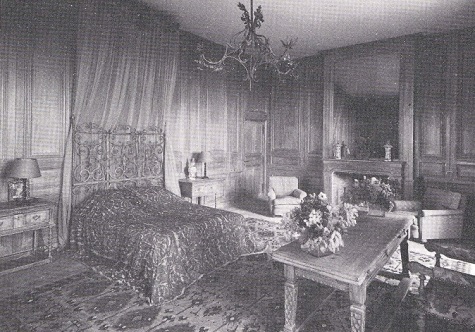

This chandelier was originally in Coco Chanel’s bedroom, hanging above her bed. Like most people who move, Mlle Chanel didn’t feel the need to take the light fixtures in her home with her. Wendy Reves, however, decided this could not stay in her new bedroom and moved it to the entryway of her home.

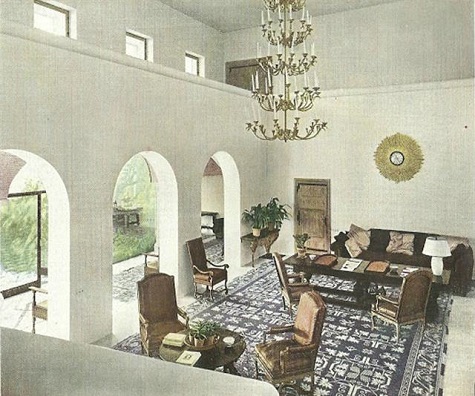

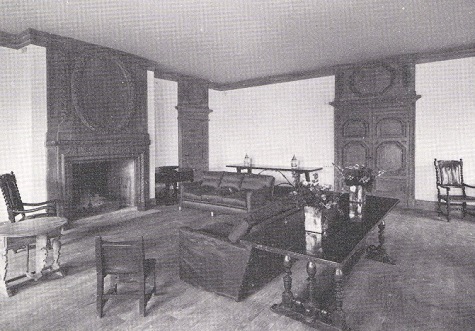

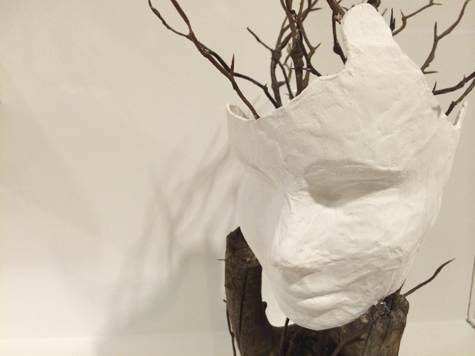

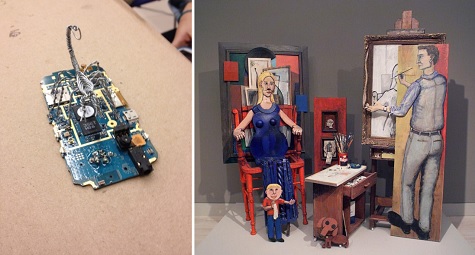

Chanel’s bedroom at La Pausa, with the chandelier now in the Reves entry and the desk at the right, now serving as a buffet table in the Reves Dining Room

This long table was originally used by Coco Chanel as a desk; however, Wendy decided that this could be useful in another way. She unfolded the leaves and moved it into her dining room to act as a buffet table.

Mlle Chanel had a set of two matching clocks, this one, which is now hanging in the Grand Hall, and another that hangs above the fireplace in the Reves Salon. When Wendy and Emery Reves moved in, they enjoyed these gold clocks and kept them in their original locations before donating them to the DMA.

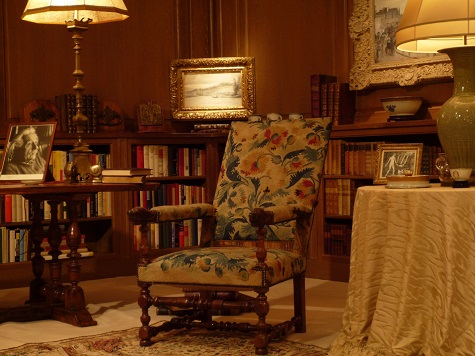

Possibly one of the coolest furniture items in the Reves Collection, this chair actually reclines using steel rods that come out of the handles. You can barely see them here, but pulling them out and pushing them in changes the recline of this chair. It is probably not as comfortable as our plush recliners today, but it was still the prototype. This early version of the recliner was originally in Mlle Chanel’s bedroom.

Originally in Mlle Chanel’s bedroom at La Pausa, this mirror didn’t travel far when Wendy and Emery Reves moved. They opted to keep it in their own bedroom. Interestingly, this is the only item that belonged to Coco Chanel that is in the Reves Bedroom.

The other side of Coco’s bedroom features the mirror now in the Reves Bedroom as well as the reclining chair now in the Library.

Of the many items in this room that belonged to Coco Chanel, we think that this yellow couch might have originally been covered in a darker fabric and left behind when she sold La Pausa. Wendy liked the color yellow and recovered the couch to fit her tastes. We can see the similarity between them when comparing the side views.

Michael Hartman is the McDermott Intern for European Art at the DMA.