A long-time favorite in the DMA’s European galleries, Camille Pissarro’s Apple Harvest of 1888 has returned to view this month after a visit to the Painting Conservation Studio.

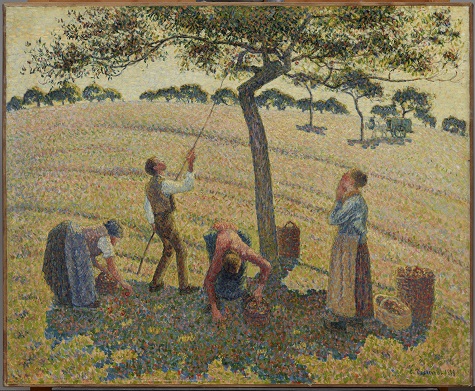

Camille Pissarro’s Apple Harvest (1888) on Mark Leonard’s easel in the DMA’s Painting Conservation Studio

Removal of the old varnish layer began at the right side of the picture, as is seen in this image taken during the cleaning process. Soft cotton swabs and a mild organic solvent mixture were used to remove the discolored resin.

The painting, which has been at the Museum since 1955, is in very good condition, but it was brought to Chief Conservator Mark Leonard to determine whether it was in need of cleaning. He opened a small “cleaning window” along the right side of the canvas, removing the layer of protective varnish. The bright pigments revealed by this small test confirmed that the varnish had become dark and yellowed over the past half-century, masking the true colors of the painting. It needed to be removed. The painting was carefully cleaned and its original vibrant tonality has been rediscovered.

- Camille Pissarro (French, 1830-1903), Apple Harvest (Cuillette des pommes), 1888, oil on canvas, 24 x 29 1/8 in. (61 x 74 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, Munger Fund; pre-treatment

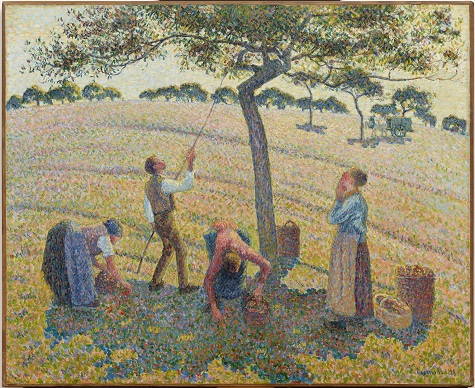

- Camille Pissarro (French, 1830-1903), Apple Harvest (Cuillette des pommes), 1888, oil on canvas, 24 x 29 1/8 in. (61 x 74 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, Munger Fund; post-treatment

Pissarro actually made three different paintings of this subject: a group of peasants gathering apples in the shade of an apple tree. The first version dates back to 1881, when Pissarro was one of the leaders of the impressionist group, and is painted in a classic impressionist style, with open brushwork describing the dappled sunlight that falls on the figures.

Camille Pissarro, Apple Picking, 1881, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 21 ¼ in. (65 x 54 cm), Private Collection

The same year, Pissarro started another, larger version of the subject, but did not complete it until 1886, when he showed it at the eighth and final impressionist exhibition.

Camille Pissarro, Apple Picking, 1881-1886, oil on canvas, 49 5/8 x 50 in. (126 x 127 cm), Ohara Museum of Art, Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture, Japan

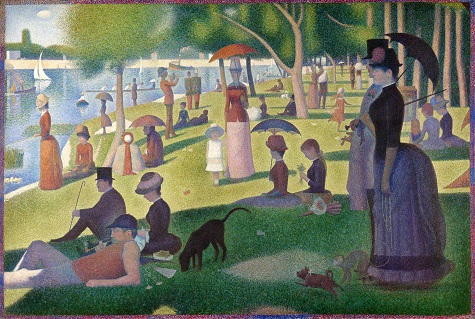

At that exhibition, Pissarro championed the participation of the young pointillist painters, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, and Seurat showed his “manifesto painting,” A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte—1884.

Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte—1884, 1884-86, oil on canvas, 81 ¾ x 121 ¼ in. (207.5 x 308.1 cm), Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection

Pissarro had recently adopted Seurat’s neo-impressionist method as the approach to painting that was “in harmony with our epoch” and an evolution from the older, “romantic” impressionism of artists like Monet. When he began work the next year on the DMA’s Apple Harvest, Pissarro was returning to a familiar subject, but armed with the new, “scientific” principles he had learned from Seurat.

Pissarro prepared the painting with a number of drawings, oil studies, and a full compositional watercolor, which he squared for transfer.

Camille Pissarro, Compositional study for Apple Harvest, c. 1888, watercolor on paper, 6 5/8 x 8 ½ in. (16.7 x 21.5 cm), whereabouts unknown

In one drawing for the apple tree, Pissarro carefully noted the local colors he observed in the grass while sketching in the apple orchard: “yellowish red-orange,” “green,” “violet,” and “pink.”

Camille Pissarro, Study for Apple Harvest, c. 1888, graphite and colored pencil on beige paper, 7 x 9 in. (17.8 x 22.7 cm), The Eunice and Hal David Collection

In the final painting, these colors were evoked optically through a flurry of carefully selected and painstakingly applied flecks and dots of pure, unmixed color.

The pointillist method was a source of ongoing internal debate for Pissarro during these years. Despite his methodical preparatory studies, Pissarro placed a very high value on freedom and improvisation in painting. In September 1888, around the time he was completing work on Apple Harvest, he wrote to his son Lucien, a fellow neo-impressionist: “I am thinking a lot here about a way of producing without the point,” he reported. “How to attain the qualities of purity, of the simplicity of the point, and the thickness, the suppleness, the liberty, the spontaneity, the freshness of sensation of our impressionist art? That’s the question; it is much on my mind, for the point is thin, without consistency, diaphanous, more monotonous than simple.”

In Apple Harvest, Pissarro went to great lengths to avoid the monotony of pointillism, and his dots are surprisingly active and diverse, fracturing and curling to define form as well as color.

Robert Herbert, one of the great 20th-century historians of impressionism, described Pissarro’s complex approach to describing the deep shadow under the apple tree at the center foreground of the painting with a myriad of colored points: “The shadow has brilliant red, intense blue, intense green as well as pink, lavender, orange, some yellow, and subdued blues and greens. The pigments were not allowed to mix much together, and preserve their individuality which, because of the high intensity, results in an abrasive vibration in our eye that cannot be resolved into one tone. In order to make the contrast still sharper, Pissarro strengthens the blue around the edges of the shadow, a reaction provoked by the proximity of the strong sunlit field.”

By February of the next year, Pissarro informed his son that he was still “searching for a way to replace the points. Up until this moment, I haven’t found what I desire; the execution doesn’t seem to me to be quick enough and doesn’t respond simultaneously enough to sensation.” Pissarro sought nothing less than translating the immediacy of his optical sensations into the solid fact of paint on a canvas. Throughout the late 1880s, he was testing the capacity of the neo-impressionists’ methods to sustain this personal artistic goal.

Camille Pissarro taking his rolling easel outdoors to paint near his house in Éragny, France, c. 1895

The first critics who saw Apple Harvest in 1889 and 1890, when it was shown at important exhibitions in Brussels and Paris, were profoundly impressed with how Pissarro managed to convey the experience of sunlight using the pointillist approach. One early critic wrote, “Truly, the canvases of M. Pissarro are today painted with the sun.” Later writers have agreed, pointing out how Pissarro “directed the light so that it appears to radiate from the depths of the scene, to activate with color everything along its path and then to issue forth in to the viewer’s space.”

How, then, does the painting’s recent cleaning alter our understanding of Apple Harvest? For many decades, the painting has appeared more yellow than Pissarro intended because of the darkened layer of varnish on its surface. This change has no doubt influenced viewers of the painting who noted the “warm” palette of the canvas, which “positively throbs with the heat of a late summer’s afternoon.” The intensely sunlit effect of the painting was, it seems, given an additional golden glow by the amber hue of the darkened varnish. But, the dazzling luminosity of Apple Harvest—its “powerful fiat lux,” in the words of one early critic—was no accident of time. It was apparent to viewers as soon as the painting left Pissarro’s easel, and now, 125 years later, the painting’s brilliant colors and lighting effects have been restored to their original, white-hot intensity.

Camille Pissarro, Apple Harvest, 1888, oil on canvas, 24 x 29 1/8 in. (61 x 74 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, Munger Fund

Celebrate Camille Pissarro’s birthday on July 10 with a visit to the newly conserved work on Level 2.

Heather MacDonald is The Lillian and James H. Clark Associate Curator of European Art at the DMA.