The C3 Visiting Artist Project is back again for 2019 with three artists from across North Texas: Karla Garcia, Spencer Evans, and the Denton-based artist collective Spiderweb Salon. Over the course of the year, we’ll be chatting with the artists to dive into the process and methodologies behind their projects presented in the Center for Creative Connections.

Our first artist of the year is Karla Garcia. Garcia’s project for C3, Carrito de Memorias (Cart of Memories), utilizes an interactive “food” cart, designed and constructed by the artist with resources at the University of North Texas Fabrication Lab. Using handmade papers, Karla invites visitors to consider our memories associated with identity, roles, and traditions when making and sharing food. We interviewed Garcia to learn more about her practice and processes as an artist. Check it out below, and visit her project in the Center for Creative Connections through the end of April!

Tell us about yourself.

I am an artist, an educator, a mother, and an MFA candidate at the University of North Texas (UNT). I am originally from the border city of Juarez, Chihuahua, where I spent my formative years before moving to El Paso, Texas. I received my Bachelor of Arts in Communication and Graphic Design from the University of Texas in El Paso, and later moved to Dallas, where I currently reside. My current practice explores the concept of home and is based on the years when I moved from Mexico to the United States.

Tell us a little about past projects that led you to apply to the C3 Visiting Artist Project.

After being accepted into the Museum Education program at UNT, part of our curriculum was to research and collaborate with fellow classmates to create education programs for various audiences at museums. I was able to do my internship at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, where I worked with the Interpretation and Public Programs fields of the Education Department. One of my responsibilities was to set up an art cart for a few hours on Fridays. I talked to visitors about the processes of art making that were relevant to the exhibitions on display and assisted in an interactive activity for the Gabriel Dawe piece Plexus #34. My supervisor and mentor Peggy Speir was invaluable in this experience as she designed a type of loom that was used for visitors to explore the same technique that Dawe used for his large-scale artworks. I enjoyed that type of interaction, where I got to learn about the visitors’ personal lives through conversation as they learned about the artist, the museum’s collection, and processes of art making. This led me to create an art cart activity for a Louise Nevelson piece, Lunar Landscape, by painting blocks of wood black to be used to form compositions and explore the artist’s creative process. These activities inspired me to design my own art cart titled Carrito de Memorias (Cart of Memories), where I explore ways of creating an engaging activity to enable the public to connect to artworks from the DMA’s collection and connect to other people through the display of the community’s personal experiences.

Tell us about the installation you’ve created in the Center for Creative Connections.

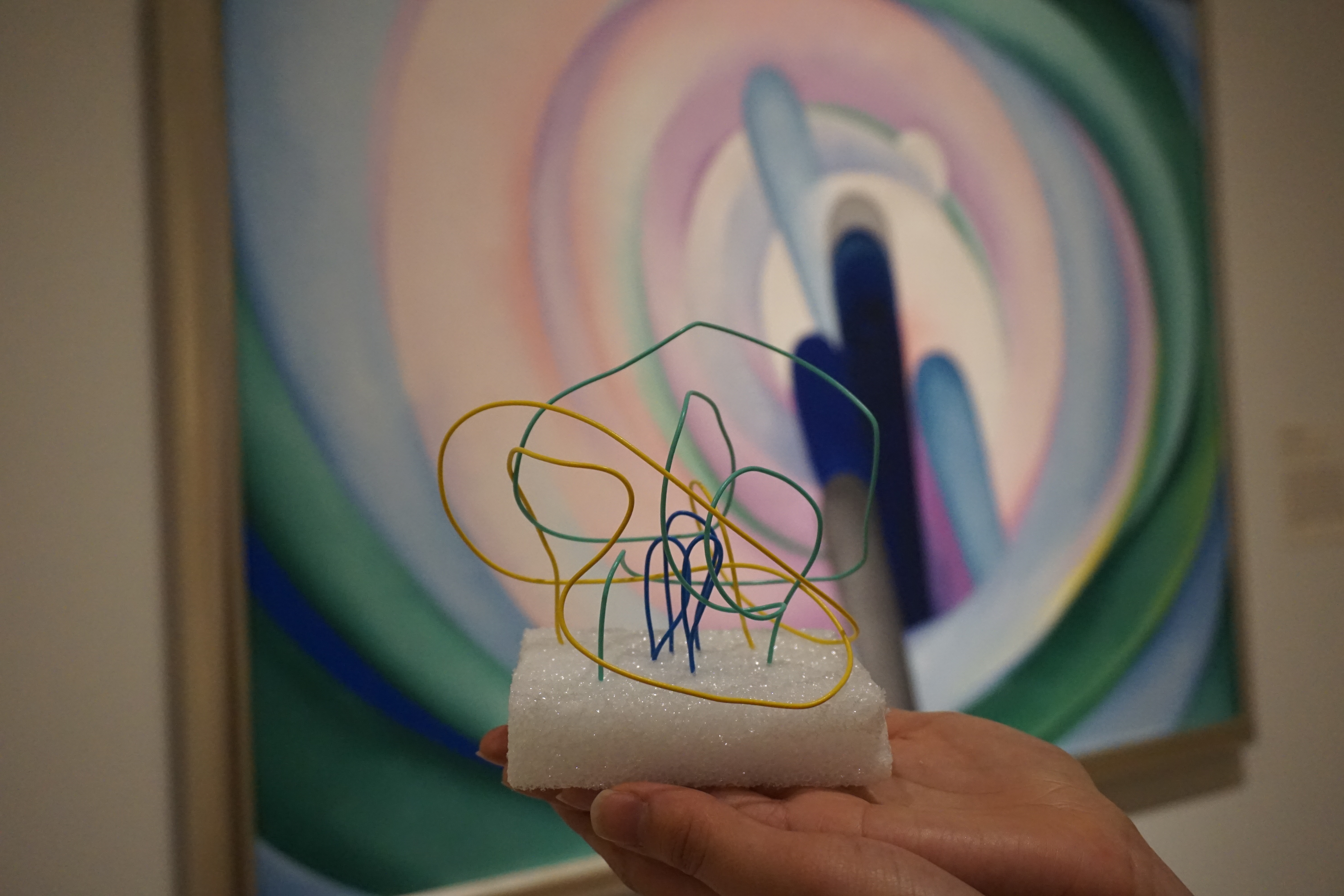

I wanted to create an art cart inspired by the history of ancient Mexico and the food carts I visited when growing up in Juarez. To me, a food cart is not only a place where food is easily accessible, but also a type of neutral space where people from all social backgrounds gather. I wanted to create this same inviting feeling for the C3 space, but rather than offering food, we are asking visitors questions that relate to the DMA’s collection regarding tradition, identity, and roles. It is a difficult thing to ask people you don’t know about their personal views, or asking them to share a memory. In my research, I have found that street food is an extension of our kitchen space. We form our traditions around food, and our families’ oral histories are passed on to us during holidays and personal celebrations, and even through daily routines. The cart became this extension of our personal spaces in our homes where everyone is welcome to share their stories. The menu on the tables around the cart have three options relating to gender roles, identity, and traditions. There are three artworks from the collection with a description that matches these categories. I’m thrilled to read everyone’s answers and see their drawings. With these, I will create sculptures that embody the public’s collective memories.

Join Karla Garcia for a Gallery Talk on Wednesday, March 20, from 12:15 to 1:00 p.m. Gallery Talks are included in free general admission. You can participate in an art-making activity related to the Carrito de Memorias installation in C3 at the FREE 2019 AVANCE Latino Street Fest / DMA Family Festival at Klyde Warren Park on Sunday, April 7, beginning at noon.

Kerry Butcher is the Education Coordinator for the Center for Creative Connections at the DMA.