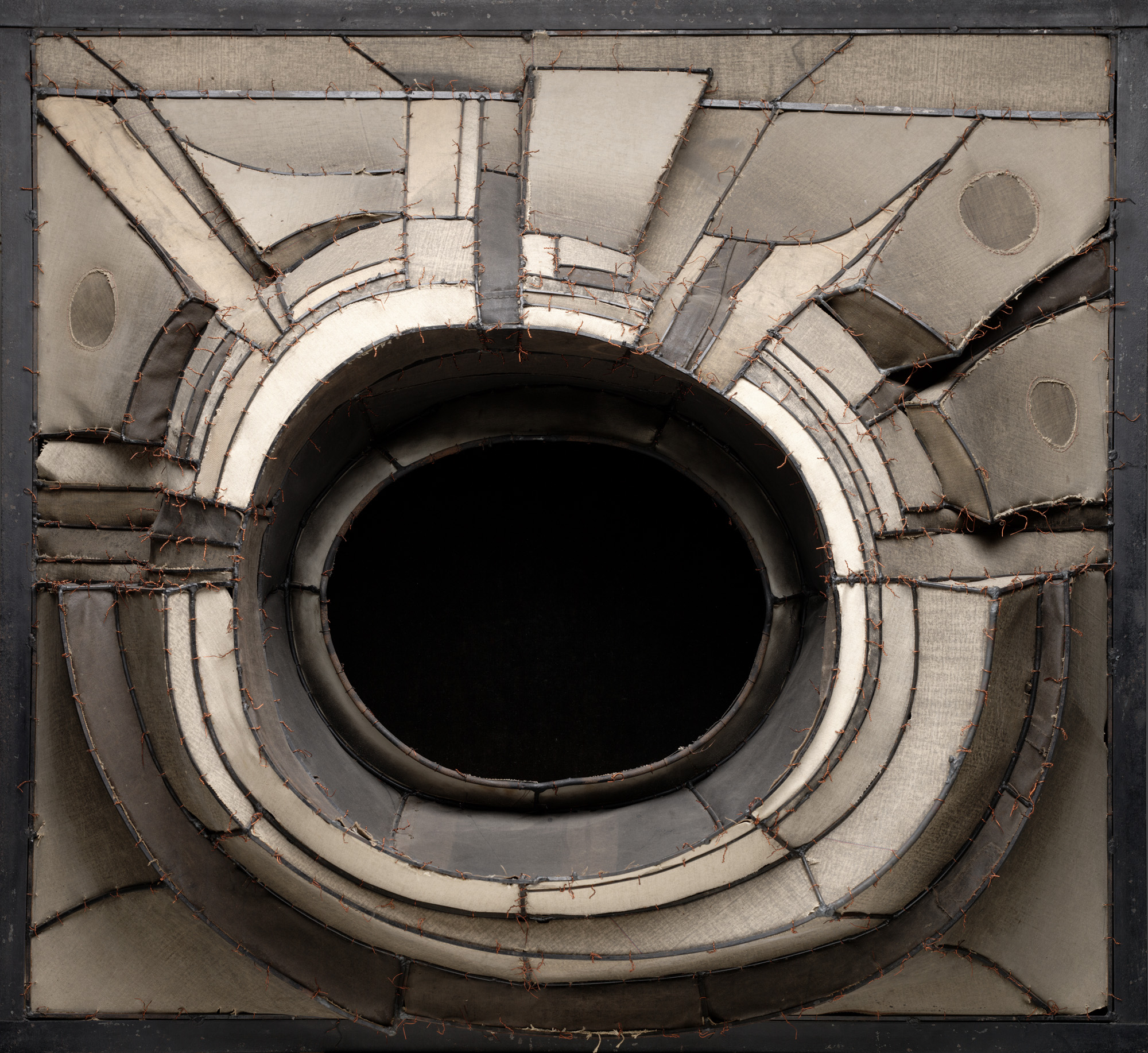

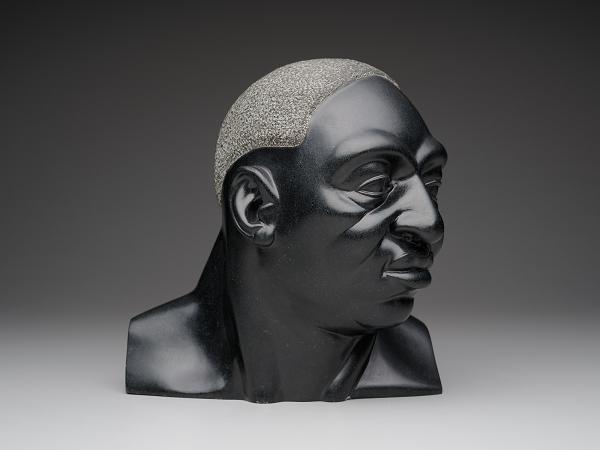

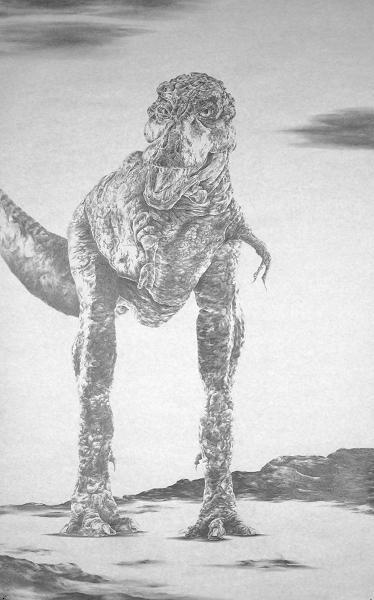

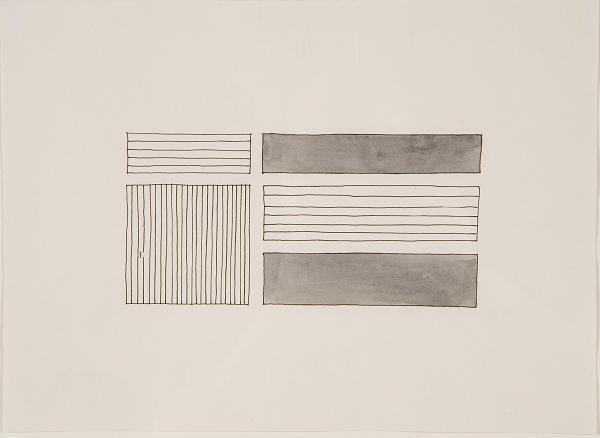

The DMA special exhibition Silence and Time has been a great springboard for conversation on tours with students and in programs with teachers this summer. Since we have just a month left to enjoy the installation, I thought it would be fun to share some new experiences and conversations it inspired, and some familiar activities we revisited. Look for a blog post in mid-August about a half-day teacher workshop in Silence and Time that incorporated some of the experiences below.

Start with silence

Prime yourself for time in the galleries by sitting in silence for a few minutes.

Silence and Time was inspired by a specific few minutes of silence: American artist John Cage’s 1952 composition 4’33.” As the introductory wall text states, “Cage’s controversial work comprises three movements…arranged for any instrument or combination of instruments. All of the movements are performed without a single note being played. The content of this composition is meant to be perceived as the sound of the environment that the listener hears while it is performed, rather than as four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence.”

What did you notice during your 4’33” of silence?

[slideshow]

Just one minute

Take just one minute to look at an artwork. When your time is up, turn so your back faces the artwork, and write down as many details about it as you can. If you’re with a friend, have him or her quiz you about the artwork with your back turned. How much were you able to notice and remember in just one minute?

Look longer

Spend fifteen minutes with just one artwork in the exhibition. Get close, move far away, and use ideas below to help you look closely.

- Create a log of what you see.

- Make a sketch of the work of art.

- Write down questions you have about the work of art.

- Write down what you like about the work of art.

- Write down what confuses you about the work of art.

- Write down how the work of art makes you feel.

Tracking time

Consider all the ways time can be measured both mechanically (clocks, calendars) and naturally (changing of seasons, hair growth, erosion). Find as many examples of ways we mark time as you can in works of art in the exhibition.

Find the time

Are there artworks that suggest suspension of time? Time moving slowly or rapidly? That time is cyclical or linear? Challenge a friend to identify different representations of time manifested in artworks in the exhibition. If you enjoy thinking about possible shapes time could take, pick up Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dreams, a collection of short stories that describe parallel universes where time behaves differently–sometimes in circles, sometimes backwards, etc.

Make your own artwork

Use make-shift art materials from your purse or pockets to create an artwork that will change with time. As you’re looking for materials in your purse or pockets, consider which objects show more or less wear and tear and which objects age more or less quickly. Then, explore the galleries looking specifically at materials the artists used.

Silence and Time is on view until August 28.

Amy Copeland

Coordinator of Go van Gogh Outreach

Art of the American Indians: The Thaw Collection

Art of the American Indians: The Thaw Collection