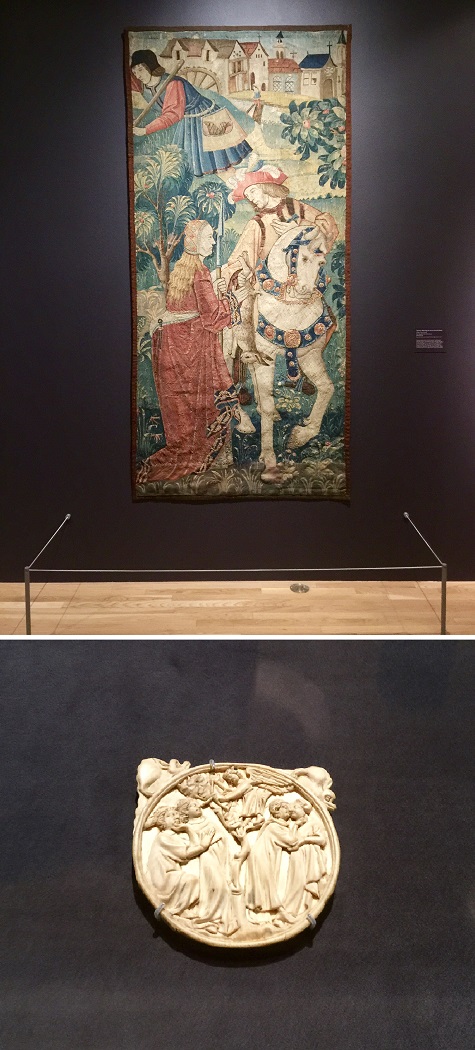

We are in the final two weeks of Art and Nature in the Middle Ages and to celebrate we are sharing insight from stain glass artist Judith Schaechter modern experience with the medium featured in the Winter 2017 issue of Artifacts.

Art and Nature in the Middle Ages explores medieval works in a variety of media, including beautiful examples of stained glass. This particular art form was perfected during the Middle Ages, and little has changed in the practice of making stained glass in the ensuing centuries. While this once fairly common medium is not widely used by contemporary artists, Philadelphia-based artist Judith Schaechter is known for her work in stained glass. Artifacts asked her why she is drawn to working in this medium and what similarities she sees between modern stained glass works and those created in the Middle Ages.

Stained glass reached its peak in the 12th century and it’s been downhill since then. Perhaps stained glass is an odd medium to choose if one wishes to participate in the world of contemporary fine art, and, indeed, it is! Yet, I found it altogether irresistible.

Although I went to art school to study painting, I knew almost instantly when I tried stained glass that it was what I wanted to pursue for the rest of my life. Why? I felt “in sync” with glass. When I was a painter, I painted fast and furiously, and ultimately threw everything out. This didn’t happen with glass because it was so labor intensive. By the time I managed to do something to the glass, I had developed feelings of attachment and was hardly going to throw it away.

I found the beauty of stained glass to be the perfect counterpoint to ugly and difficult subjects. Although the figures I work with are supposed to be ordinary people doing ordinary things, I see them as having much in common with the old medieval windows of saints and martyrs. They seem to be caught in a transitional moment when despair becomes hope or darkness becomes inspiration. They seem poised between the threshold of everyday reality and epiphany,

caught between tragedy and comedy.

My work is centered on the idea of transforming the wretched into the beautiful—say, unspeakable grief, unbearable sentimentality, or nerve-wracking ambivalence—and representing it in such away that it is inviting and safe to contemplate and captivating to look at. I am at one with those who believe art is a way of feeling one’s feelings in a deeper, more poignant way.

Medieval windows sought to confer inspiration and enlightenment on those who saw them. Beholding a stained glass window can enable, encourage. and literally enact the process of being filled with light. It sounds like some kind of preternatural phenomenon, but it’s a physical fact. While one is busy identifying and empathizing with the image, one also experiences physically the warming, filling sensations of light. It’s so persuasive not because the pictures are convincing narratives but because the colors are overwhelming and the light is sublime—and, by golly, it’s coming from inside you, it’s part of you.

Judith Schaechter has lived and worked in Philadelphia since graduating in 1983 with a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design Glass Program. Her work is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Ar t, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Hermitage, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Corning Museum of Glass, the Renwick Galler y of the Smithsonian Institution, and numerous other public and private collections.