Whimsical. Unsettling. Surreal. These are a few of the adjectives used to describe the look and feel of the exhibition Dalí’s Divine Comedy, coming soon to the DMA. As the 2019-2020 Dedo and Barron Kidd McDermott Intern Fellow for European Art, I was given the opportunity to curate an exhibition of works on paper in a space in the European galleries on Level 2, drawing from the Museum’s rich collection of European prints and drawings. Exhibition planning comes several months (if not years for large exhibitions!) in advance before the works even touch the wall. Thus, I arrived at the DMA at the beginning of my tenure in mid-August last year with my sleeves rolled up and ready to work.

Dali’s Divine Comedy brings together works from prominent Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí’s series illustrating The Divine Comedy. Written by Florentine poet Dante Alighieri in 1320, this long narrative poem charts Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise in search of salvation.

In 1950 the Italian government commissioned Dalí to illustrate The Divine Comedy in celebration of Dante’s 700th birthday. Although the request was later revoked, Dalí, likely inspired by the poem’s imaginative qualities and its potential for fantastical illustrations, persisted with this project. From 1951 to 1960 he created 100 watercolors representing each canto (or section) of the poem. The watercolors were later transferred to colored wood engravings. This series, containing 100 prints, came into the DMA’s collection in 1996 as a gift from collectors Lois and Howard B. Wolf.

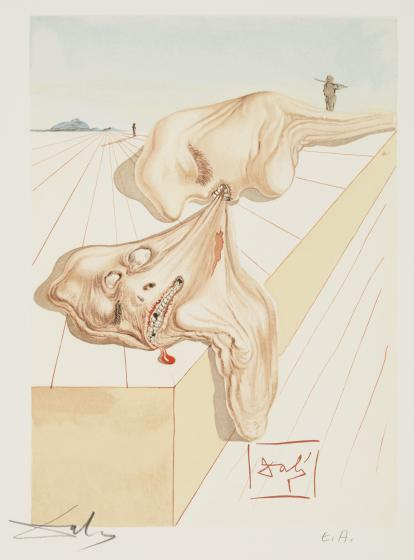

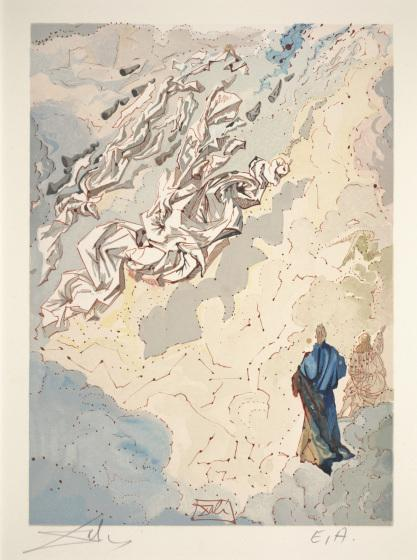

Following the narrative cycle of its original literary source, Dalí’s Divine Comedy opens with a presentation of Dante’s depictions of Hell. Dalí visually reinterprets this realm as a barren, empty landscape crawling with strange amorphous forms as illustrated in the print Hell: Men Who Devour Each Other (Canto 30). His radical articulation of space demonstrates his unique Surrealist spin on the frightful qualities traditionally ascribed to Hell. Instead of depicting Hell as a fiery inferno, Dalí portrays this region as a vast empty space that conjures comparable feelings of terror.

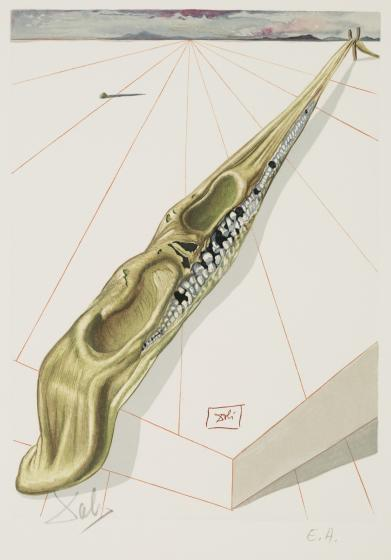

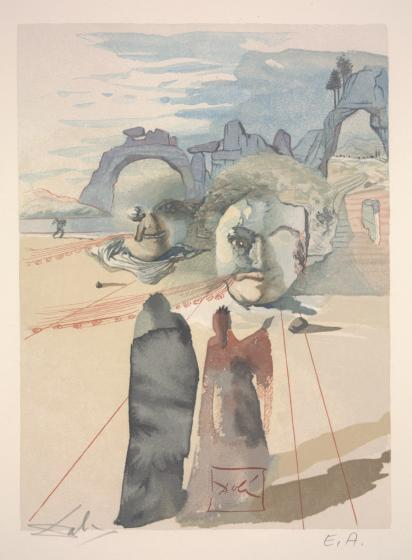

Echoing the liminality, or state of in-betweenness, that characterizes Purgatory, Dalí recycles visual strategies employed in his renderings of Hell and Heaven to illustrate scenes from this region. In Purgatory: Avarice and Prodigality (Canto 20), sharp lines seen in Hell resurface in Purgatory, mediated by dynamic watercolor forms that distinguish Heaven. Dalí also provides up-close portraits of the realm’s inhabitants, providing a psychoanalytic glimpse into the complex nature of repentance.

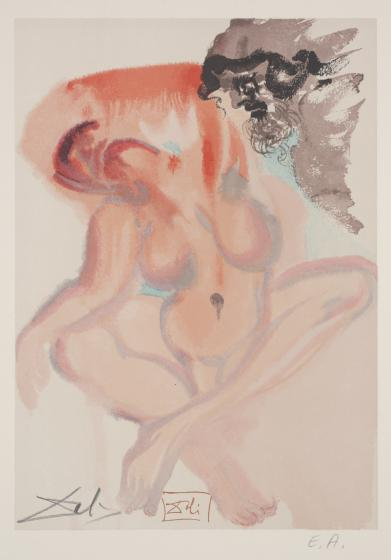

Visitors will find Dalí’s seemingly placid though uncanny representations of Heaven in stark contrast to the scenes presented in the previous two realms. Dalí depicts the celestial cosmos with vibrant, warm watercolors as illustrated in Paradise: The Angel (Canto 2). The loose, fluid brushstrokes that compose the painterly form of the angel resonate with the ethereal properties that Dante ascribes to Heaven.

Perhaps the most visually striking element among these prints is Dalí’s persistent use of tiny geometric forms, which he refers to as rhinoceros horns, to make up the bodies of the angels and spirits that Dante encounters in Heaven. Dalí developed a peculiar interest in these forms during the later phase of his career claiming that they served as his sources of “angelic inspirations.”

Dalí employs different visual aesthetics in his depiction of each realm while also guiding the viewer to consider the timeless paragone, or interaction between word and image, through his illustrations. The DMA’s exhibition Dalí’s Divine Comedy presents these varying perspectives, all while encouraging an endless pursuit of fantasy, play, and imagination.

Chasitie Brown is the Dedo and Barron Kidd McDermott Intern Fellow for European Art at the DMA.