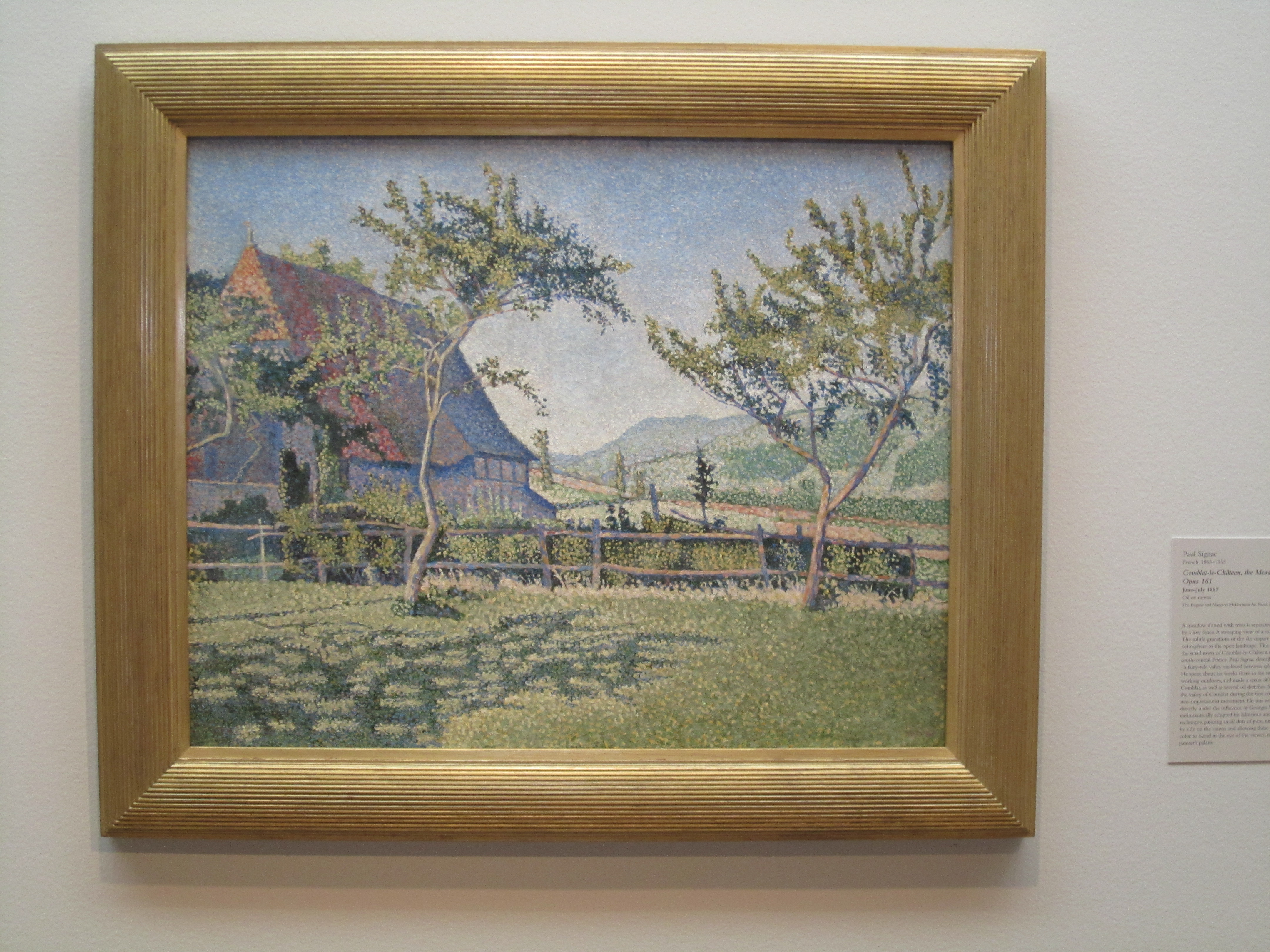

The existing Dallas Museum of Art collections handbook was published in 1997. Considering all of the stellar acquisitions that have taken place in the last fifteen years, we felt the time was right to publish a new one. The process took months of preparation and many meetings to create the new guide, which will be available in the Museum Store early next year.

In a series of conversations, DMA curators and former DMA Director Bonnie Pitman came up with a timeline, and agonized over the book’s structure (for example, does Romare Bearden’s Soul Three belong in the Contemporary or the Modern section? Should European and American art be combined?). The group also came up with an “A” and a “B” list of objects to be considered for inclusion in each of the sections.

The process for paring these lists down was grueling for all concerned. Sacrifices and compromises were made. As a biased participant, I had my own favorite objects, and anxiously awaited the outcome of each meeting. My beloved College of Animals by Cornelis Saftleven was out of the running early on, owing to urgent conservation needs, but I had the pleasure of seeing this work restored to the European and American section late in the process.

Cornelius Saftleven, "College of Animals," n.d., oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, The Karl and Esther Hoblitzelle Collection, gift of the Hoblitzelle Foundation, 1987.32

I worked on the entries with the curators, interns, and freelance contributors. This catalogue has given me a newfound appreciation for the many works of art I had always admired in passing but never really focused on. Immersing myself in object files or staring at the objects in the galleries, I added many new discoveries to my list of personal favorites.

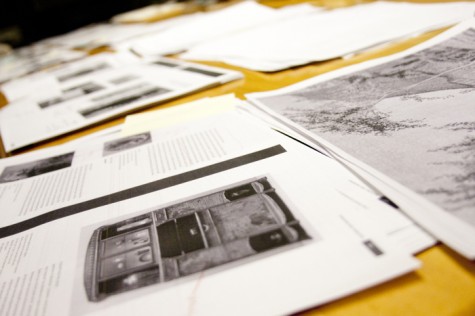

Perhaps the most fascinating part of the process was the ordering and grouping of objects within their sections. We plastered the walls of our “Classroom B” conference room with color printouts of all four hundred-plus objects, taped or pinned in constantly migrating clusters. It was ultimately quite satisfying to see the groupings crystallize; every invidious or inept grouping eventually led us to the final fortuitous solution. This was a creative process, appealing to the artist in me.

Eric Zeidler is the Publications Manager at the Dallas Museum of Art.