Did you know that a former DMA director was a Monuments Man?

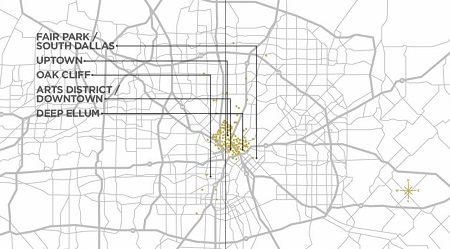

Richard Foster Howard was director of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts from December 1935 to May 1942. Howard arrived in Dallas to oversee the completion of the new museum in Fair Park and the grand Texas Centennial exhibition in 1936. He would go on to assemble the exhibition for the Pan-American Exposition in 1937 and start the Texas General, an annual juried exhibition of Texas artists.

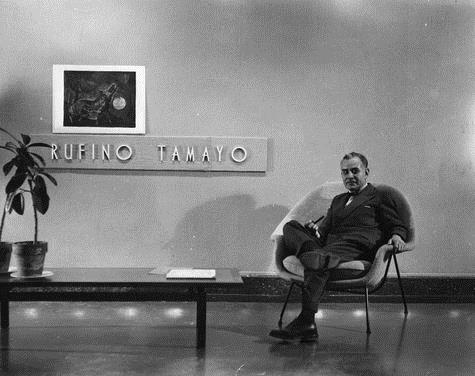

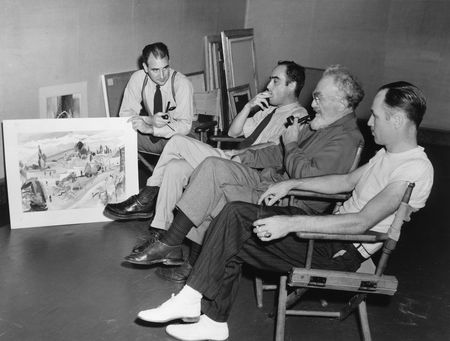

Richard Foster Howard (standing) with jurors Xavier Gonzales, Donald Bear, and Frederick Browne judging the Texas section of the Greater Texas and Pan-American Exposition, 1937

Jurors for the 1941 Texas General exhibition: (L to R) Richard Foster Howard, John McCrady, Boardman Robinson, and W. Whitzle

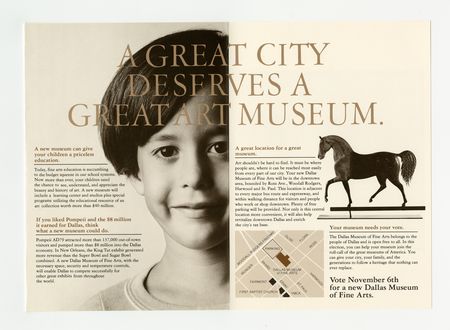

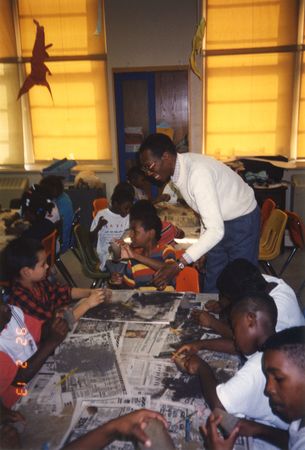

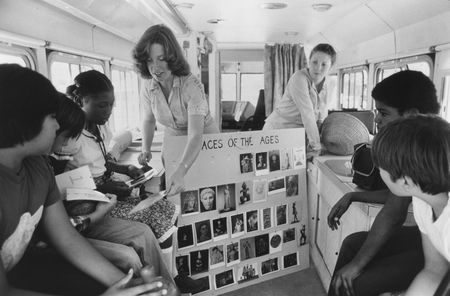

Education was a major focus of his tenure as director. Howard started free Saturday classes for children in 1937, began the school tour program with the Dallas Independent School District in 1937-38, established the education department with the hiring of Mrs. Alexandre (Maggie Jo) Hogue as the first full-time supervisor of education in 1939, and founded the Museum’s library in 1940.

During World War II, Howard retired from the Museum to join the army and was made a captain in the Army Field Artillery. He served in the European theater with distinction and returned to Germany in July 1946 as deputy chief of monuments, fine arts, and archives for the Office of Military Government for Germany (U.S.) He served as a Monuments Man until December 1948. For his service in returning works of art removed by Germans during the war, he was awarded the Order of the White Lion of Bohemia by the Czechoslovakian government and the Star of Italian Solidarity by the Italian government.

When Howard returned from Germany, he resumed his museum career, retiring as director of the Birmingham Museum of Art in 1975.

This Friday, learn even more about this special group of men and women with the opening of The Monuments Men movie.

Hillary Bober is the digital archivist at the Dallas Museum of Art.

![Visitors using audio tour, circa 1960s [Photography by Pat Magruder]](http://blog.dma.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/audio_tour_0012.jpg)