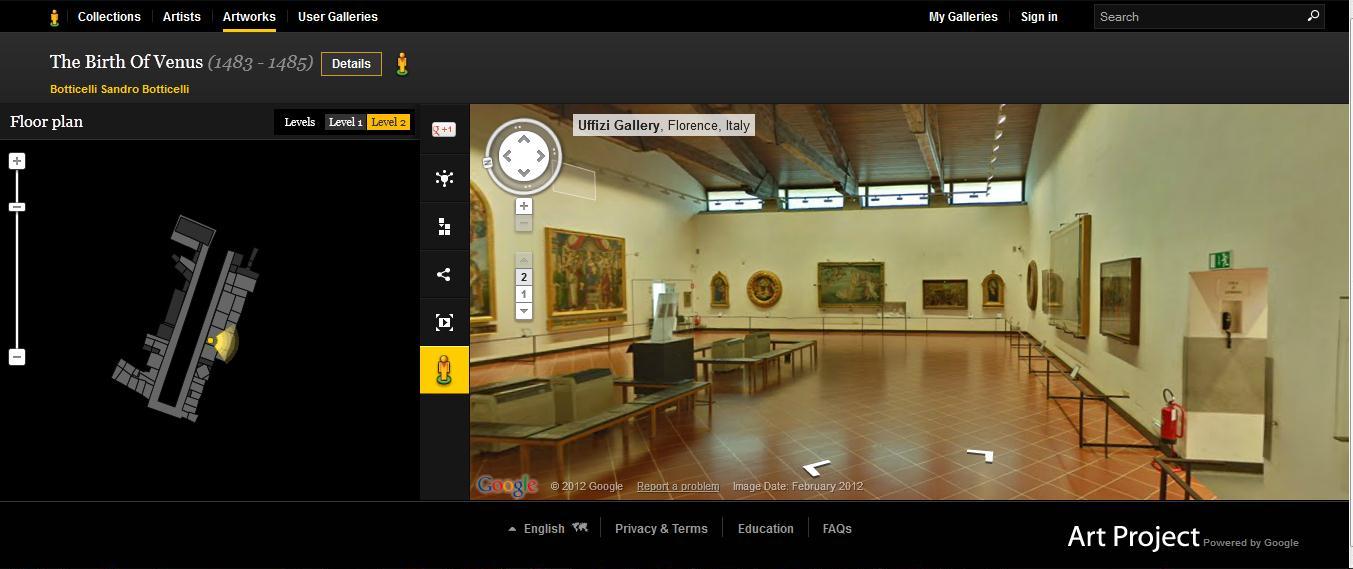

Most of us usually experience artworks from books, magazines, and by visiting our local museums and art galleries. There are countless artworks all over the world that most of us will not get an opportunity to see in person. Wouldn’t it be amazing if students in Dallas could take a field trip to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City? How about a trip to Florence, Italy to view The Birth of Venus in the Uffizi Gallery, or a trip to Hong Kong, China to visit the Hong Kong Heritage Museum?

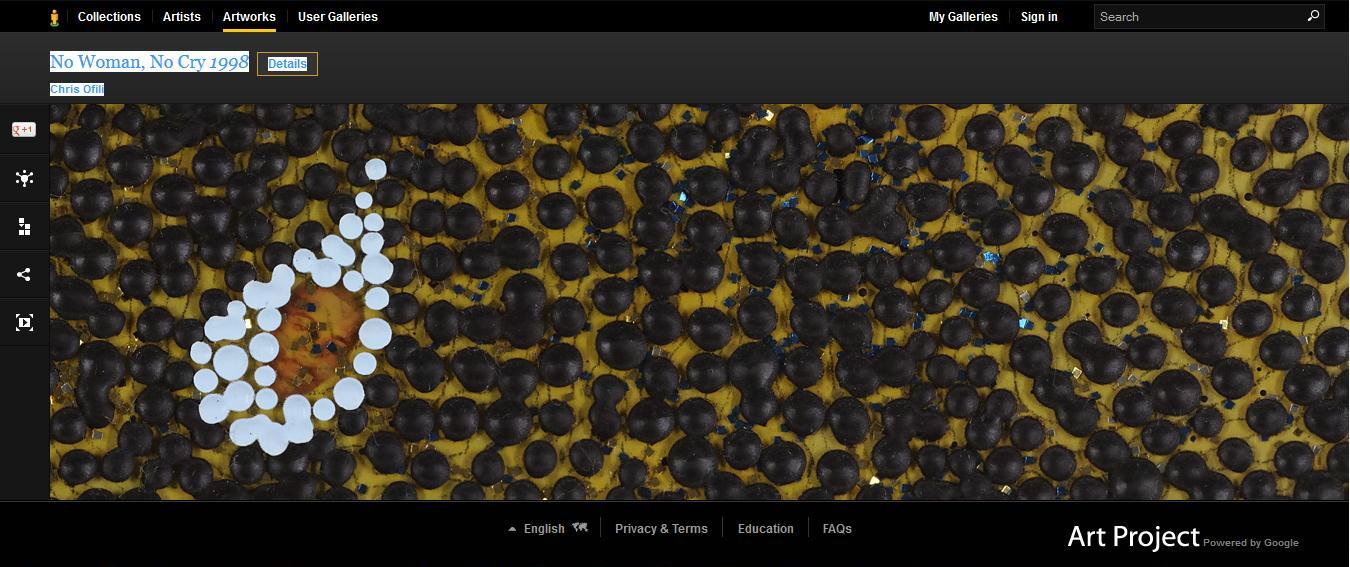

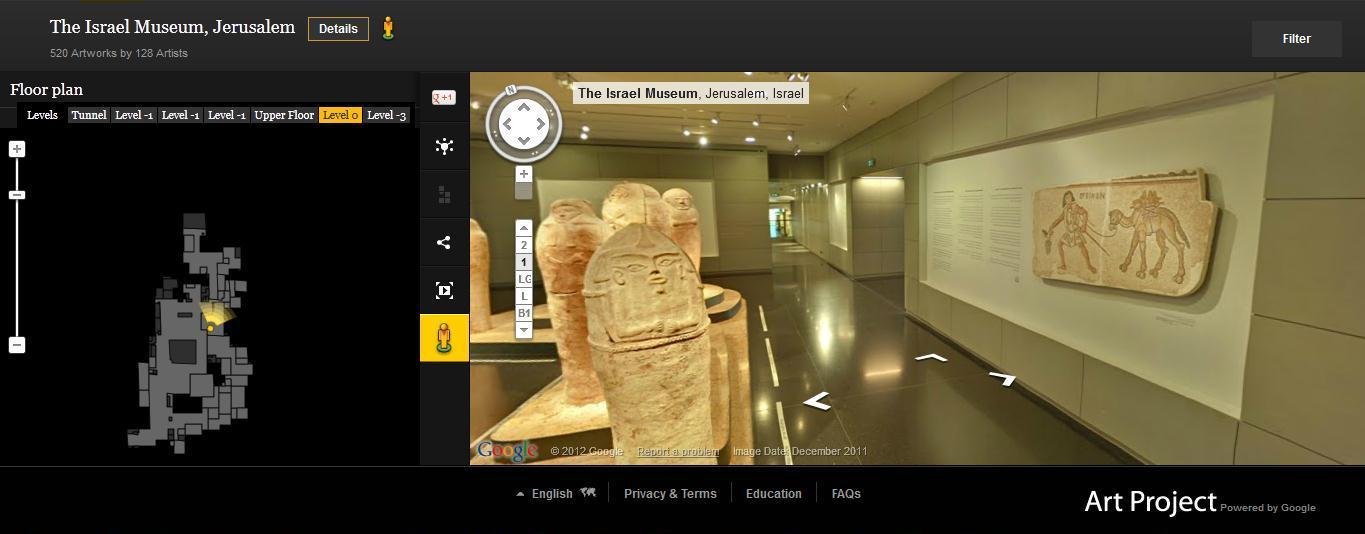

Google has created a way to virtually visit these museums. Thanks to the Google Art Project, anyone with internet access can have a virtual tour of artworks, and gallery spaces in major art centers all over the world. Students in any part of the world can get online and experience artworks that they may otherwise not have access to.

Right now you may be thinking, “This sounds good, but what exactly is the Google Art Project, and how does it work?” Here is a preview.

My first encounter with the Google Art Project took place about a year ago while taking a museum education class at the University of North Texas. My instructor Dr. Laura Evans approached a few of the students about the possibility of presenting on the Google Art Project at the 2011 Texas Art Education Association Conference in Galveston, TX. After doing some research on this project, Jessica Nelson, Nicole Newland, David Preusse, and I decided to work as a team under the leadership of Dr. Evans. Our presentation, Virtual Museum Field Trips: The Google Art Project was aimed at providing ways in which high school art teachers could incorporate the Google Art Project into their classrooms. Afterward, we received positive feedbacks from the teachers in attendance.

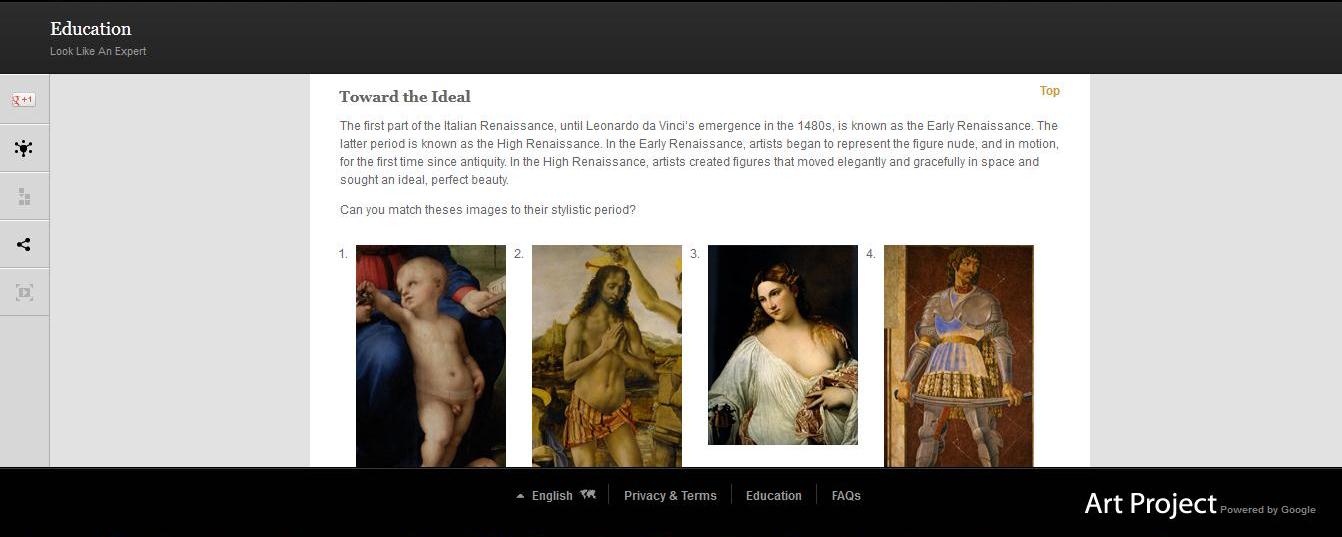

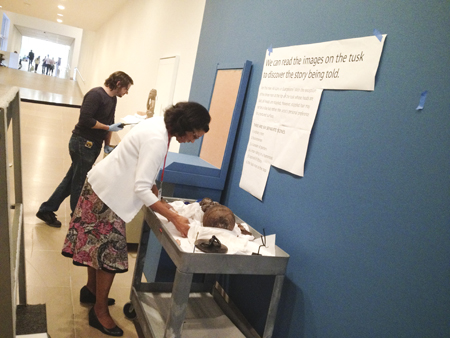

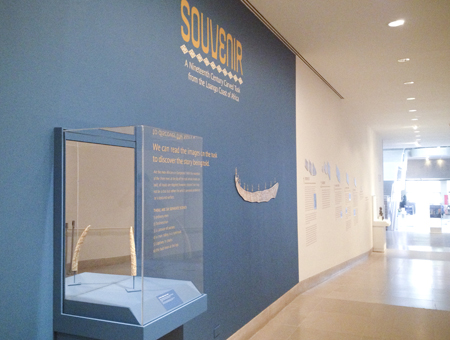

Currently, the Google Art Project features artworks and gallery spaces from selected collections worldwide. This project is relatively new and still developing. Similar to the street view and navigation features in Google Maps, the Google Art Project provides an interior view and navigation of art galleries and museums. It is structured to emulate a viewer’s perspective within the space. You can easily navigate from one gallery space into the next, zoom in and out of artworks, and get more information on each artwork. Moreover, you can log in and create your own personal gallery collection of your favorite artworks.

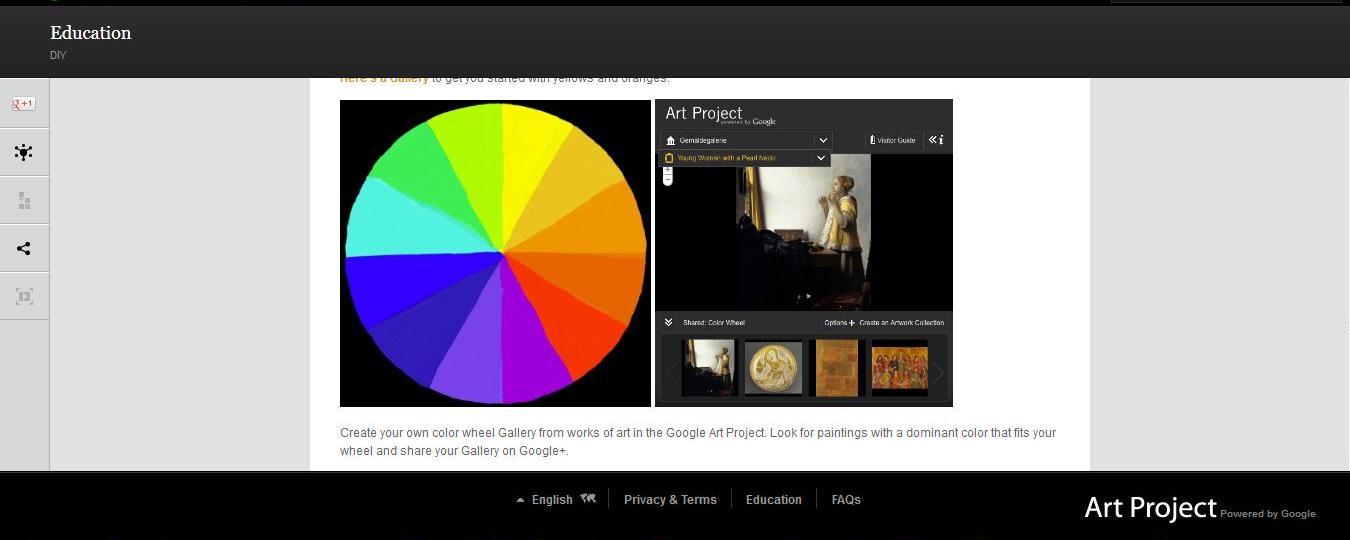

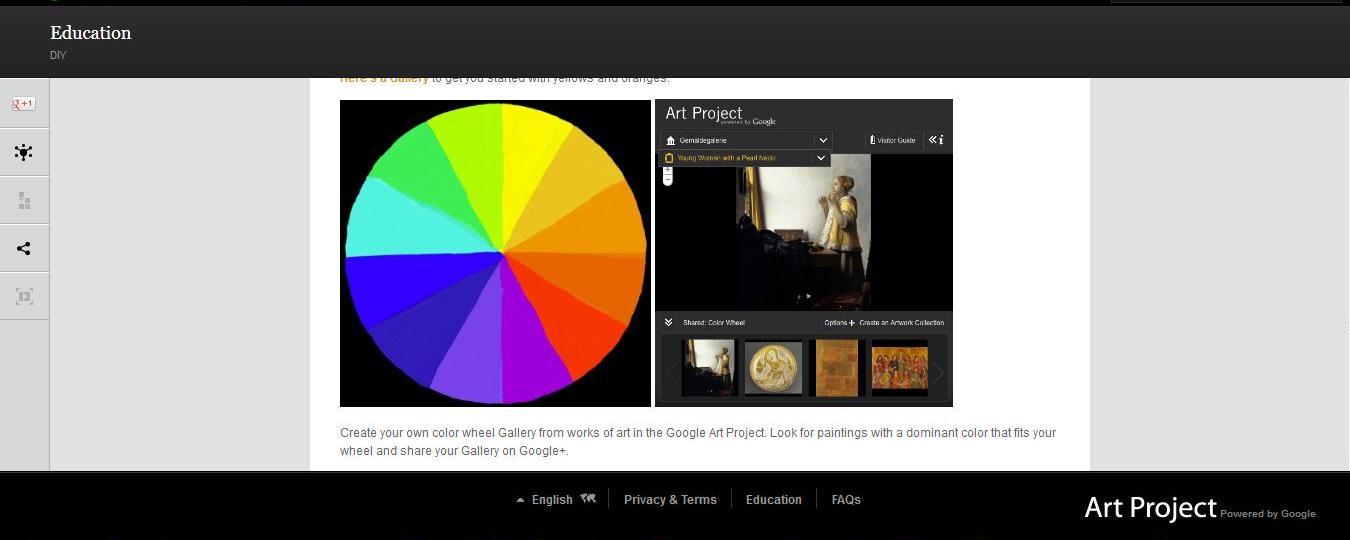

The Google Art Project is easy to use, and its structure encourages countless possibilities for art education activities in K-12 art classrooms. Some suggestions for activities include:

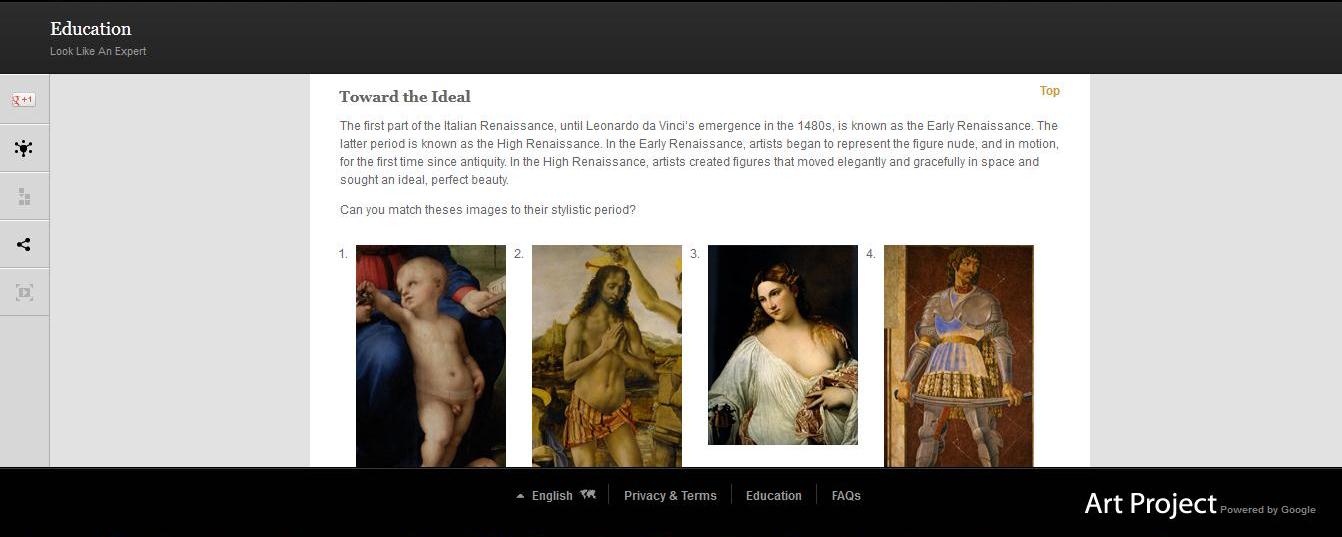

- Comparisons – compare and contrast artworks in the same space or in different galleries.

- Art critique activities – describe, interpret, and critique works of art.

- Personal collections – curate customized art collections for classroom projects.

- Imaginative narratives – write stories inspired by artworks in the same gallery space.

- Original artworks – create artworks inspired by a gallery space or by selected artworks in different museums.

Below is a summary of one of the art activities I created and presented during the TAEA conference.

Activity: Compare and Contrast: ARTexting

Grade: High school

Objective: Using the notion of texting, students create an informed conversation between two artworks in a gallery space. This ARTexting activity encourages students to make decisions and insightful observations as well as develop personal connections and individual creativity.

Outline:

- Choose two artworks in the same gallery space that are displayed facing each other.

- Imagine what these artworks would say if they could send text messages to each other.

- Which artwork will send the first text? How will the second artwork respond?

- What interesting facts will they learn about each other?

- Students should research basic facts about their selected artworks and write a possible conversation that the artworks could have via texting.

- The dialogue should be fun and also informative.

Example

Museum: Uffizi Gallery, Florence Italy

Artworks:

Sample text dialogue:

Portinari: Hello Goddess of Love, what’s up?

Venus: Nothing much, I am just emerging from the sea. It’s so cold out here. You look warm over there with all those bright outfits!

Portinari: Lol. We have baby Jesus here. Some shepherds stopped by to check him out.

Venus: Ohh how fun! But why is he on the floor?

Portinari: He is really humble – he was born in a manger

Venus: Oh I see. That must be his mom next to him. How cool!

Portinari: …

Venus: …

This activity was inspired by considering how the Google Art Project could relate to high school students. The education link on the Google Art Project provides more ideas and examples of activities, suggestions, and videos from a variety of experts. Such resources can be useful to classroom teachers, students, museum educators, or anyone interested.

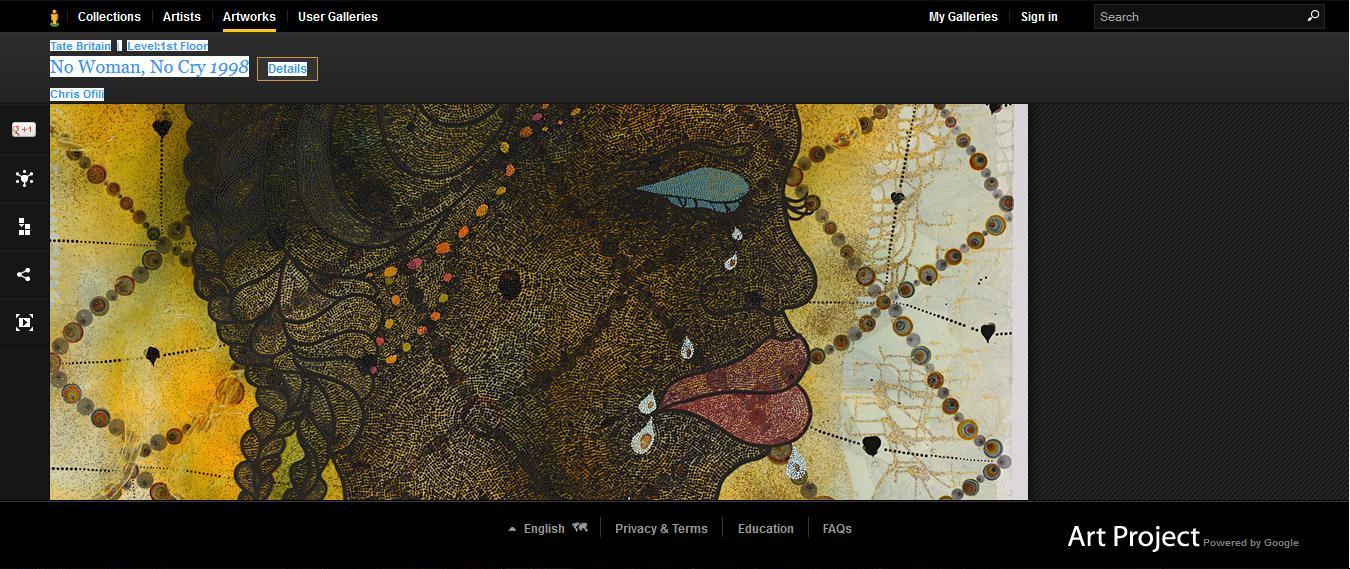

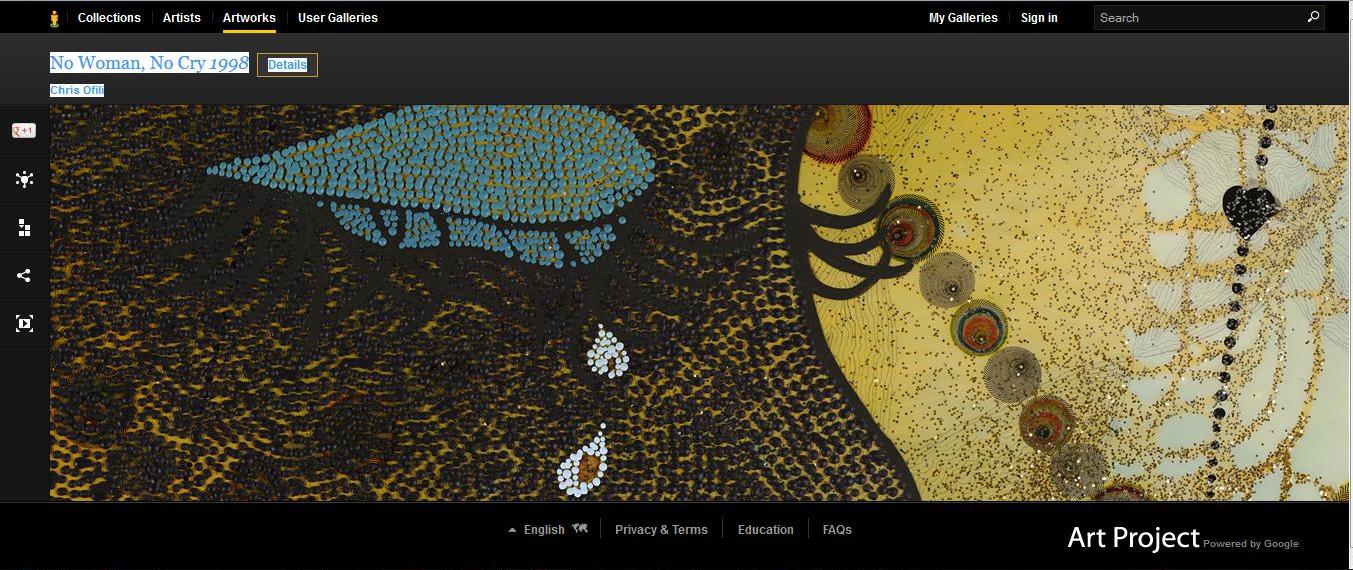

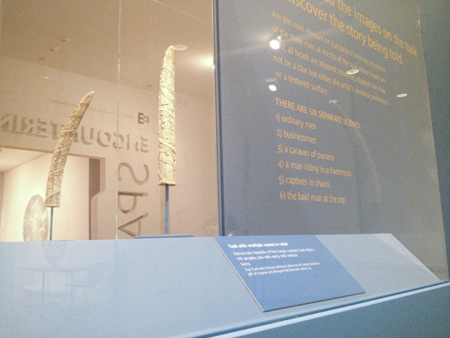

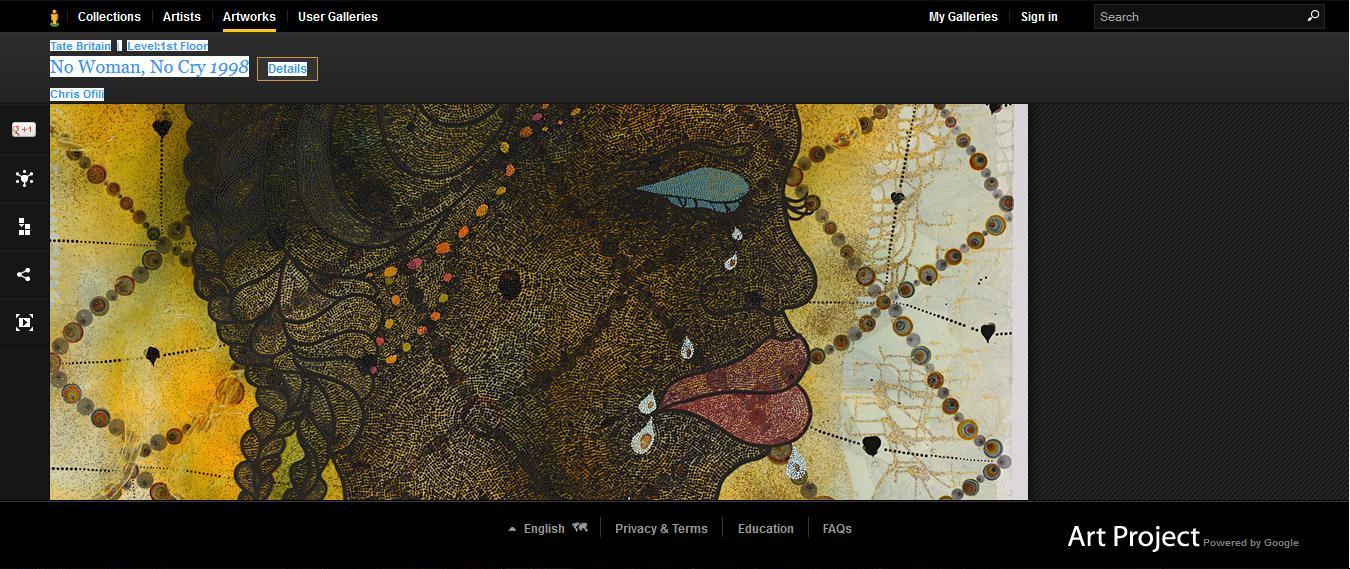

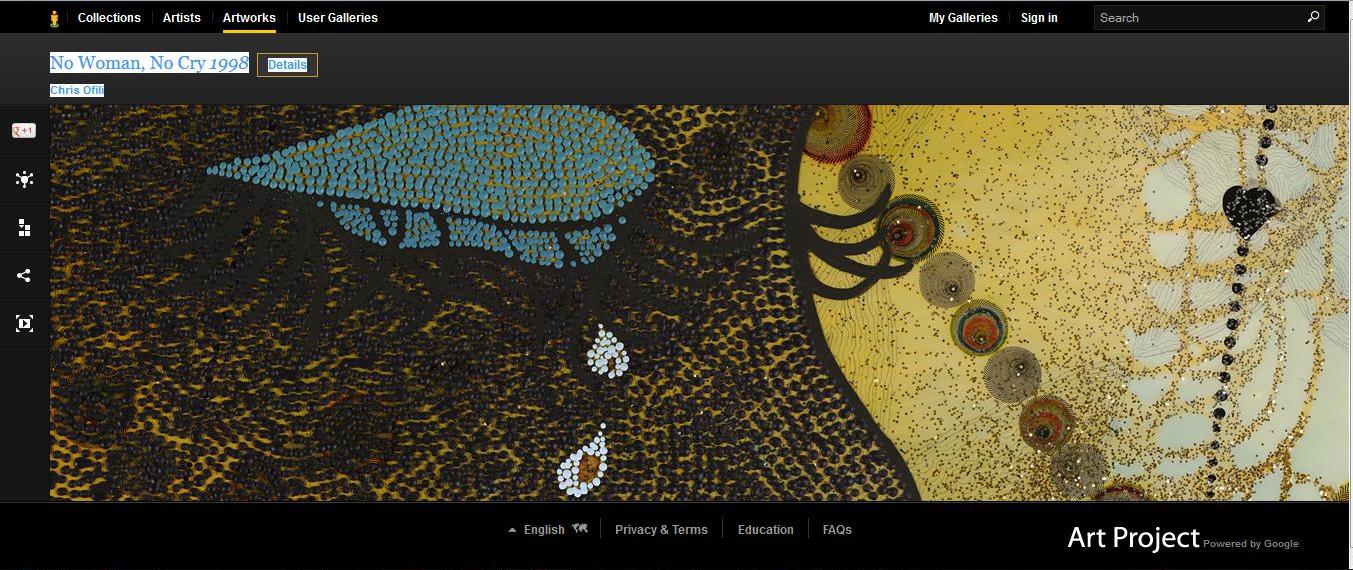

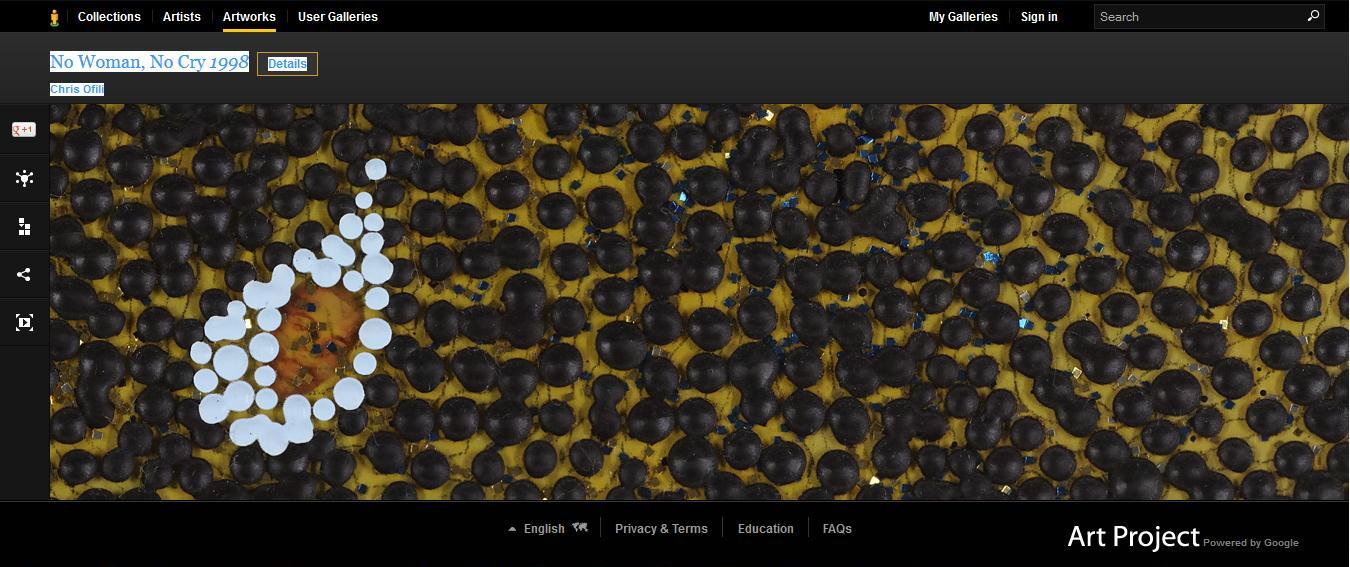

The zoom in feature is remarkable. Unlike being in a museum that has restrictions on how close you can get to artworks, the Google Art Project allows you to zoom in and experience every texture, form, or brushstroke of an artwork.

The Google Art Project is truly an innovative approach to making art available to the masses. It provides new ways to interact with artworks and exciting tools for art education. Moreover, it is free and available to anyone with internet access. This means that a student in my home country of Cameroon can have access to artworks in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City as well as artworks in the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City. This Google initiative is certainly at the core of arts advocacy, as it creates cross-cultural connections by making the arts more accessible across the globe.

The Google Art Project makes art accessible to everyone. So, do not wait any longer – visit www.googleartproject.com and let your exploration begin!

Mary Nangah

Community Teaching Assistant