Today is National Radio Day, and yesterday, August 19, was National Aviation Day. The two days celebrate the development and technological advancements in aviation and the invention of the radio. While it is most likely coincidental that both holidays fall back-to-back, in terms of 1930s industrial design, this pairing is meant to be.

- Ronald Reagan as a WHO Radio Announcer in Des Moines, Iowa, 1934-37. Courtesy Ronald Reagan Library.

The years between World War I and World War II were the Golden Age of Flight and the Golden Age of Radio in America. During these decades, affordable, safe, and comfortable long distance plane trips became a foreseeable travel option for the greater American public. Similarly, the affordability of the radio brought families across the United States together for regular nightly programming and entertainment—essentially bringing the world into their living room. With both the skies and airways now within reach, the fascination with rapidly developing technology, speed, and motion became hallmarks of the era.

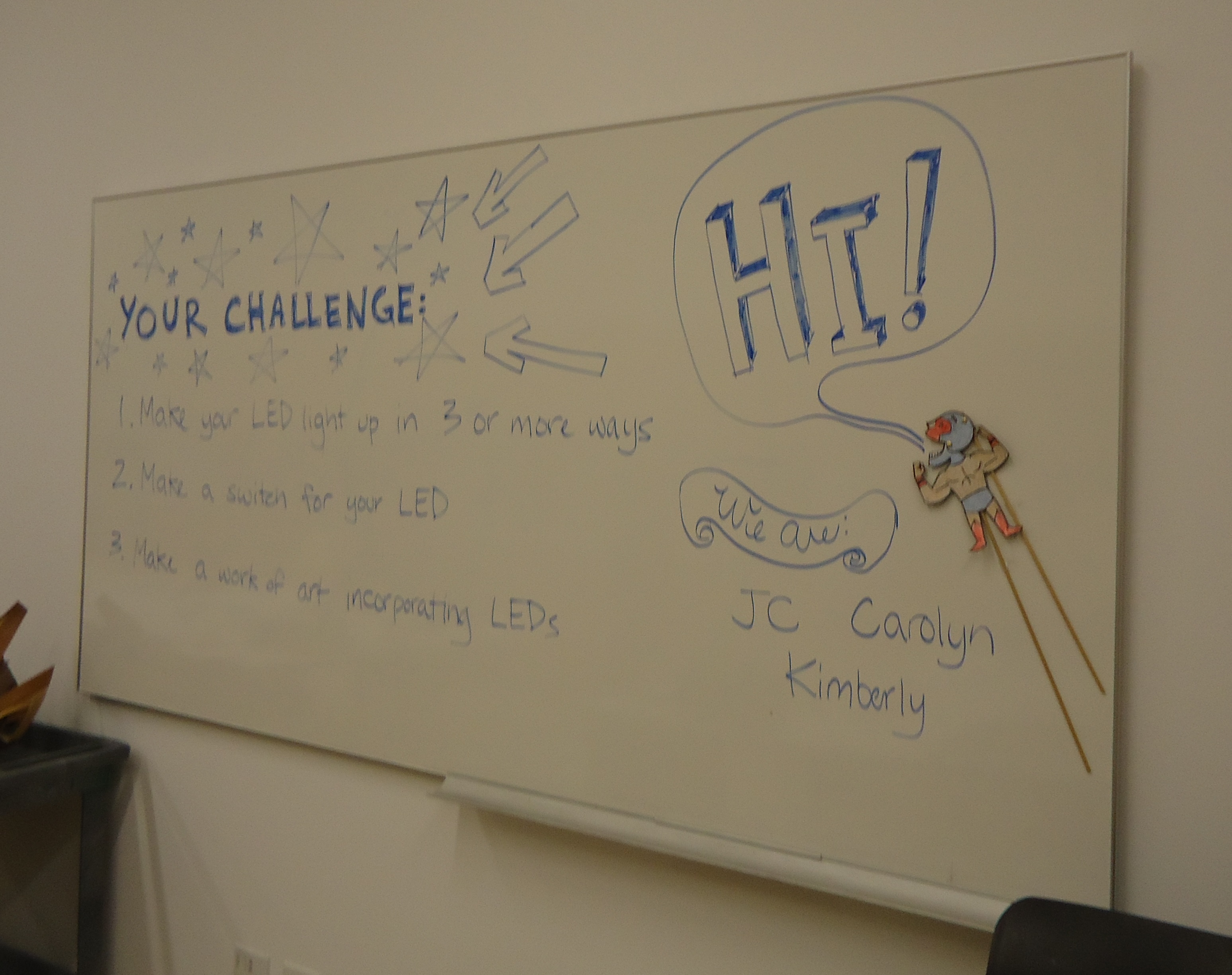

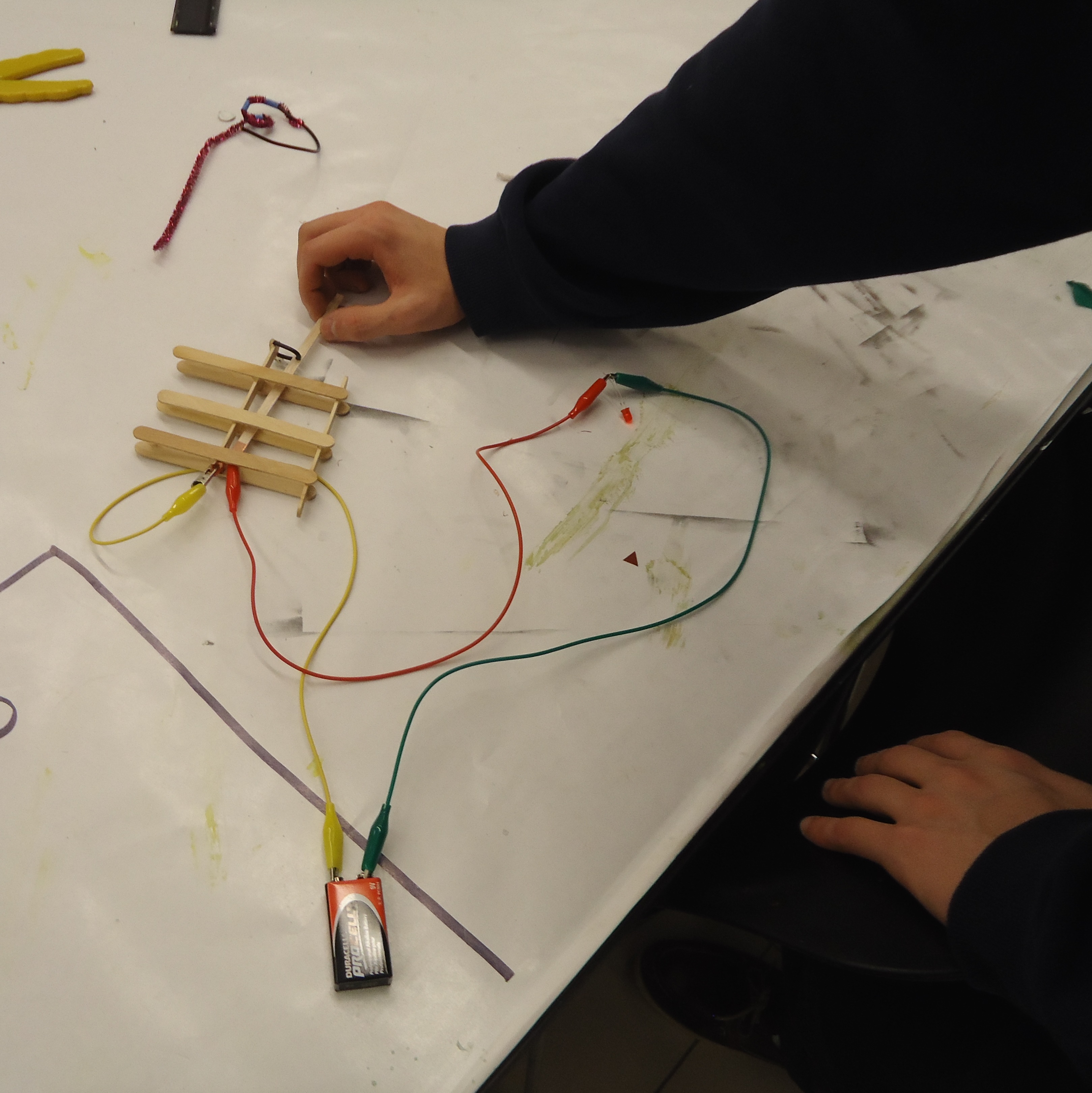

Artistically speaking, this era is one of my favorite periods in terms of the decorative arts. The emergence of flight had a profound impact on the design of many household and consumer goods during the interwar years, and radio encasements often reflected the Machine Age aesthetic of the 1930s. Prominent industrial designers of the day embraced America’s love affair with flight and successfully blurred the lines between art and technology with of-the-moment consumer products. Good design sells; therefore, it is no surprise that for the radio—one of the most prominent fixtures in the 1930s American household—overall design aesthetic often dominated the purchasing decision of a design-savvy consumer.

- A TWA Douglas DC-3 is prepared for takeoff from Columbus, Ohio, in 1940.

- Photograph of a young girl listening to the radio during the Great Depression. Franklin D. Roosevelt Library Public Domain Photographs.

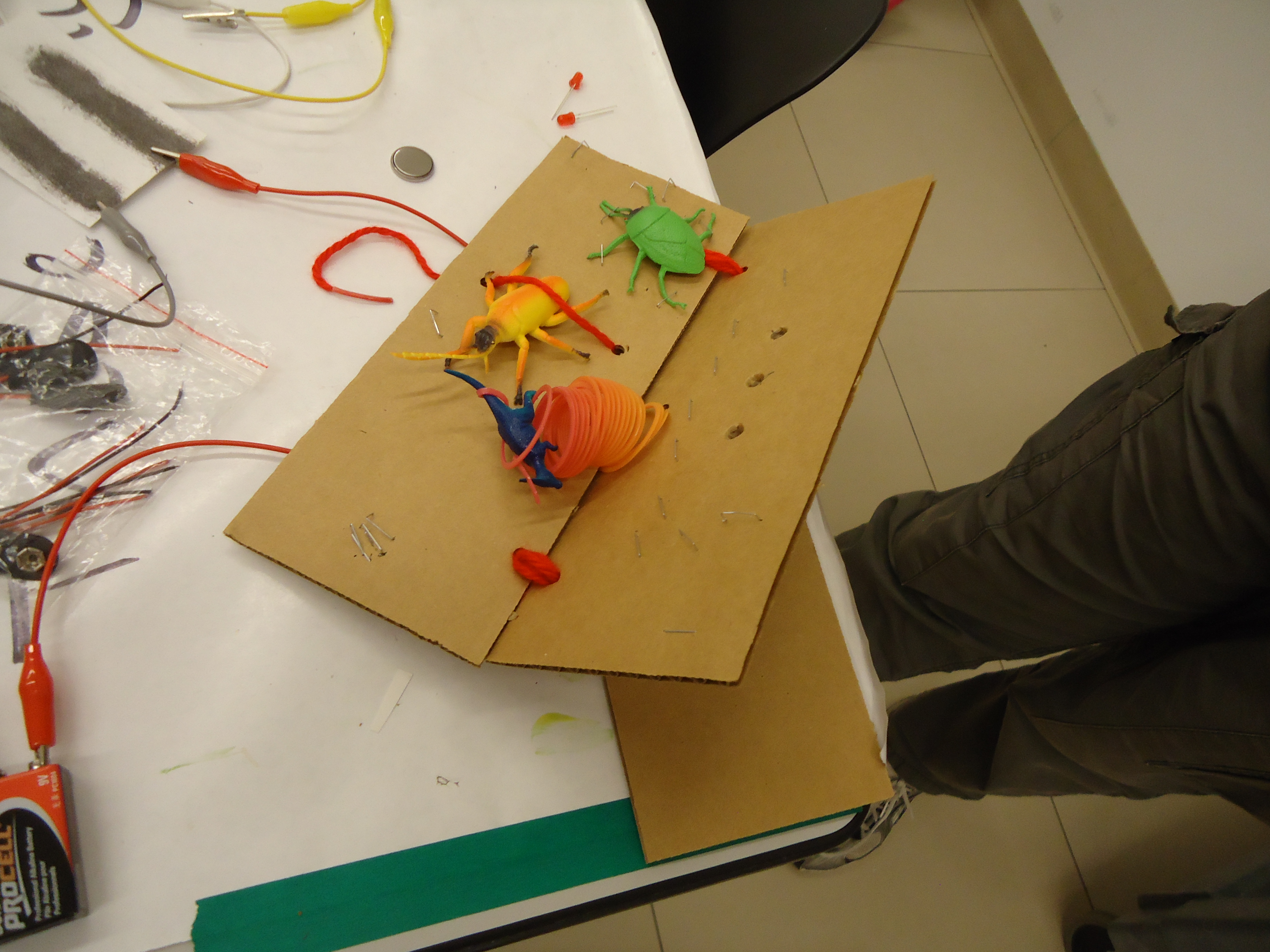

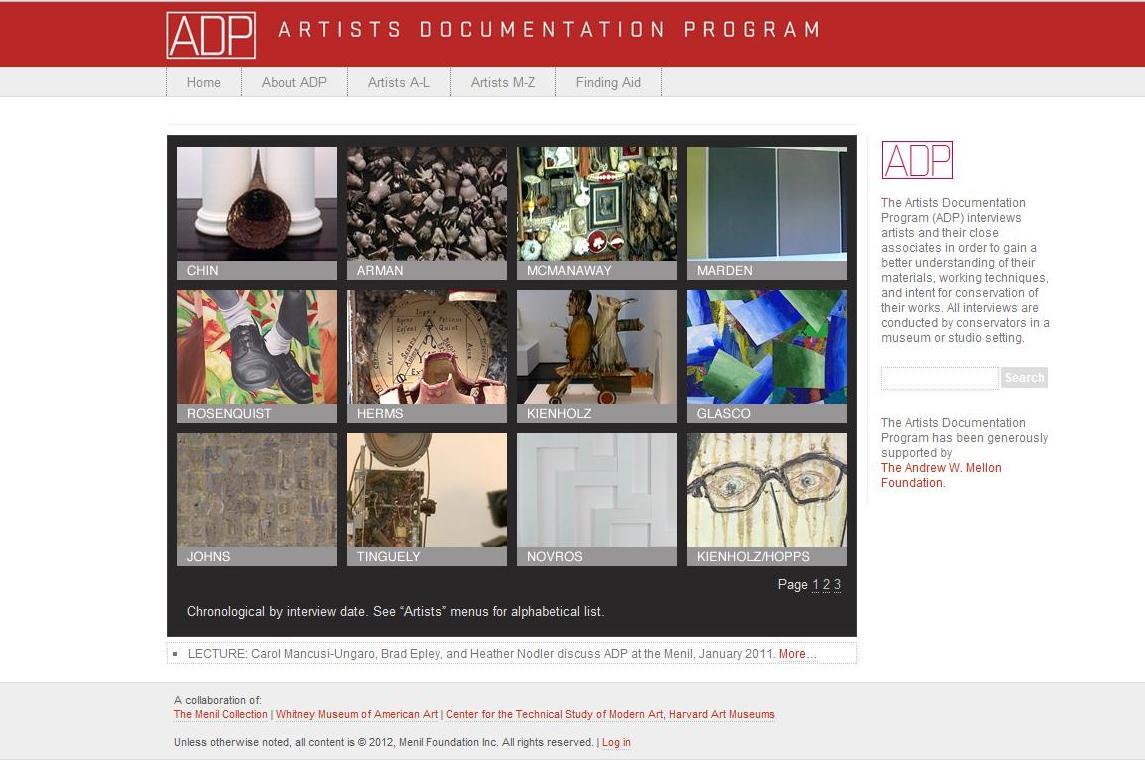

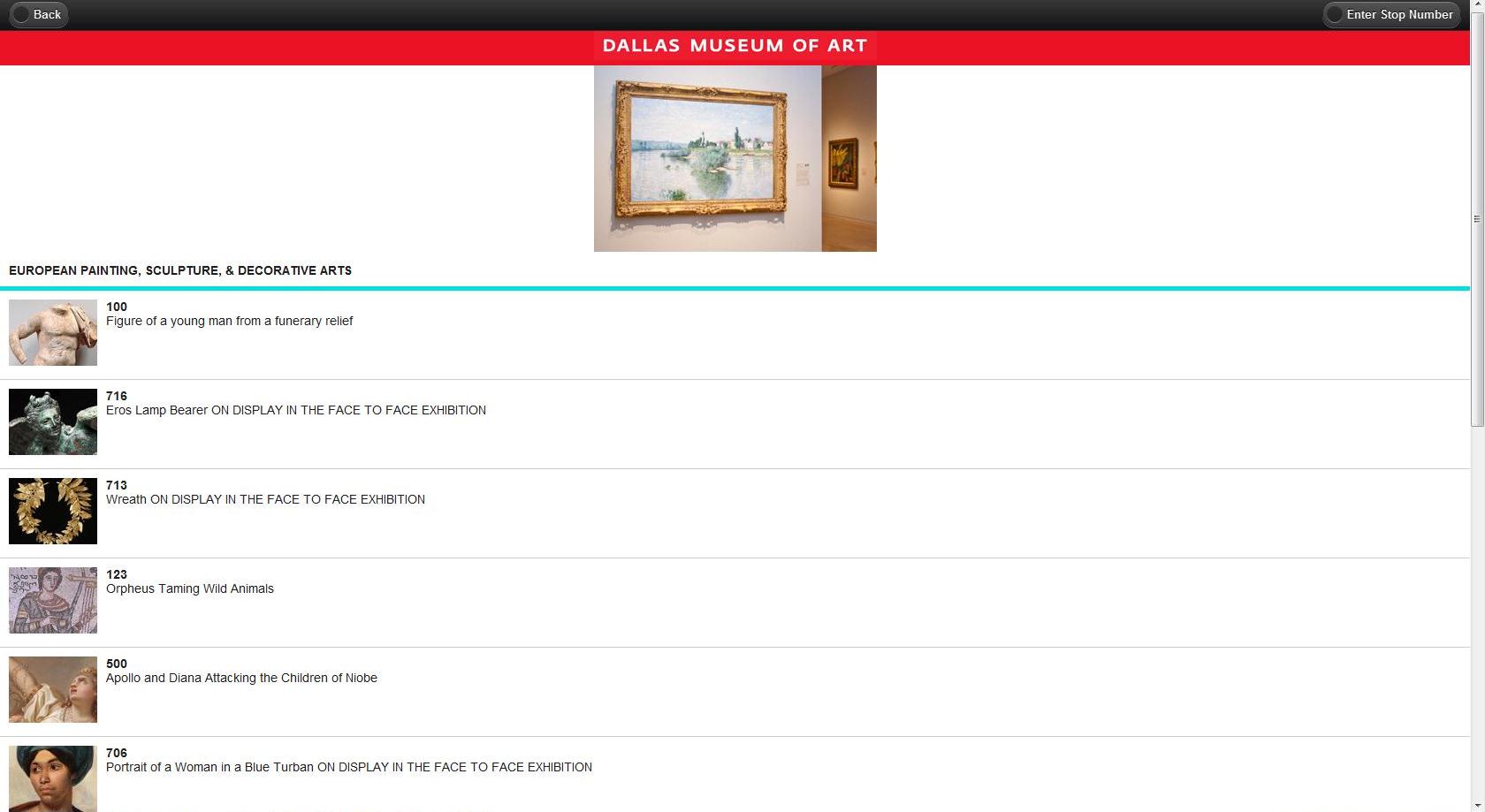

If you’re looking for a creative way to pay homage to these two holidays, take note of these aerodynamic gems on view at the Dallas Museum of Art that incorporate characteristic elements of streamline design, including horizontal banding, smooth exteriors, and the use of modern materials like chrome and plate glass. Each object suggests the concepts of speed and movement while stylishly capturing a moment in decorative art and design history when the worlds of aviation and radio effortlessly collide.

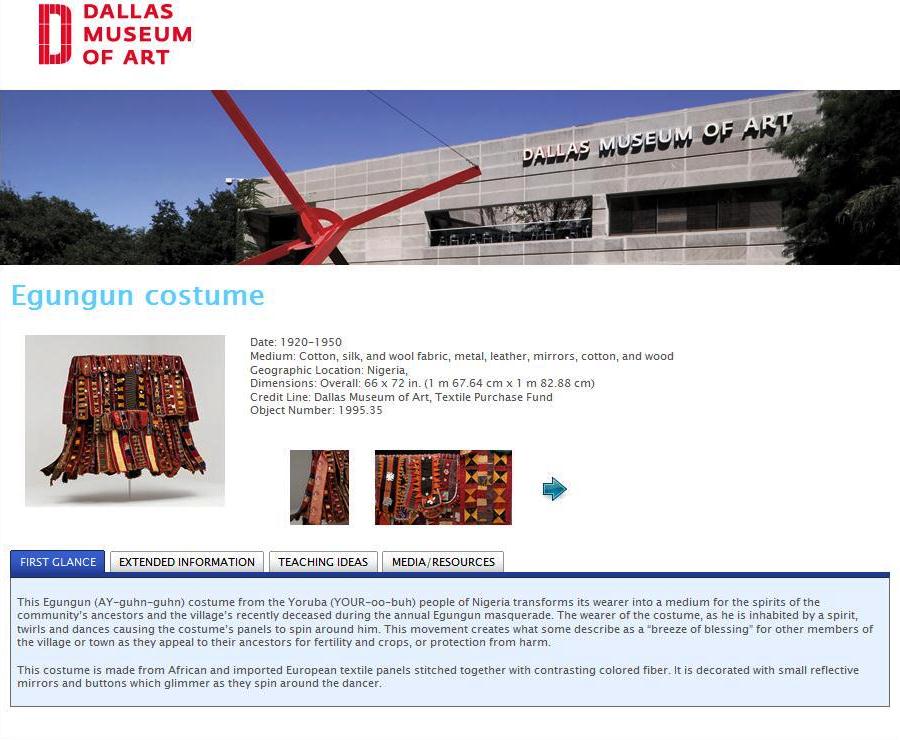

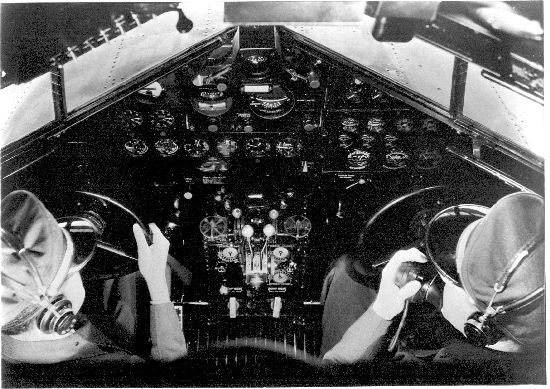

Take a look at the 1933 “Air-King” radio (model 66) designed by Harold Van Doren and John Gordon Rideout. The form of this radio is a play on the motif of a skyscraper, with its stepped shape toward the top; however, the circular glass plate on the façade with showing AM and FM broadcast band numbers, combined with the tuning and volume knobs, remind me of a cockpit’s control panel.

- Harold Van Doren and John Gordon Rideout, “Air King” radio, 1933, Dallas Museum of Art, 20th-Century Design Fund, 1999.50

- San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives, via Wikimedia Commons

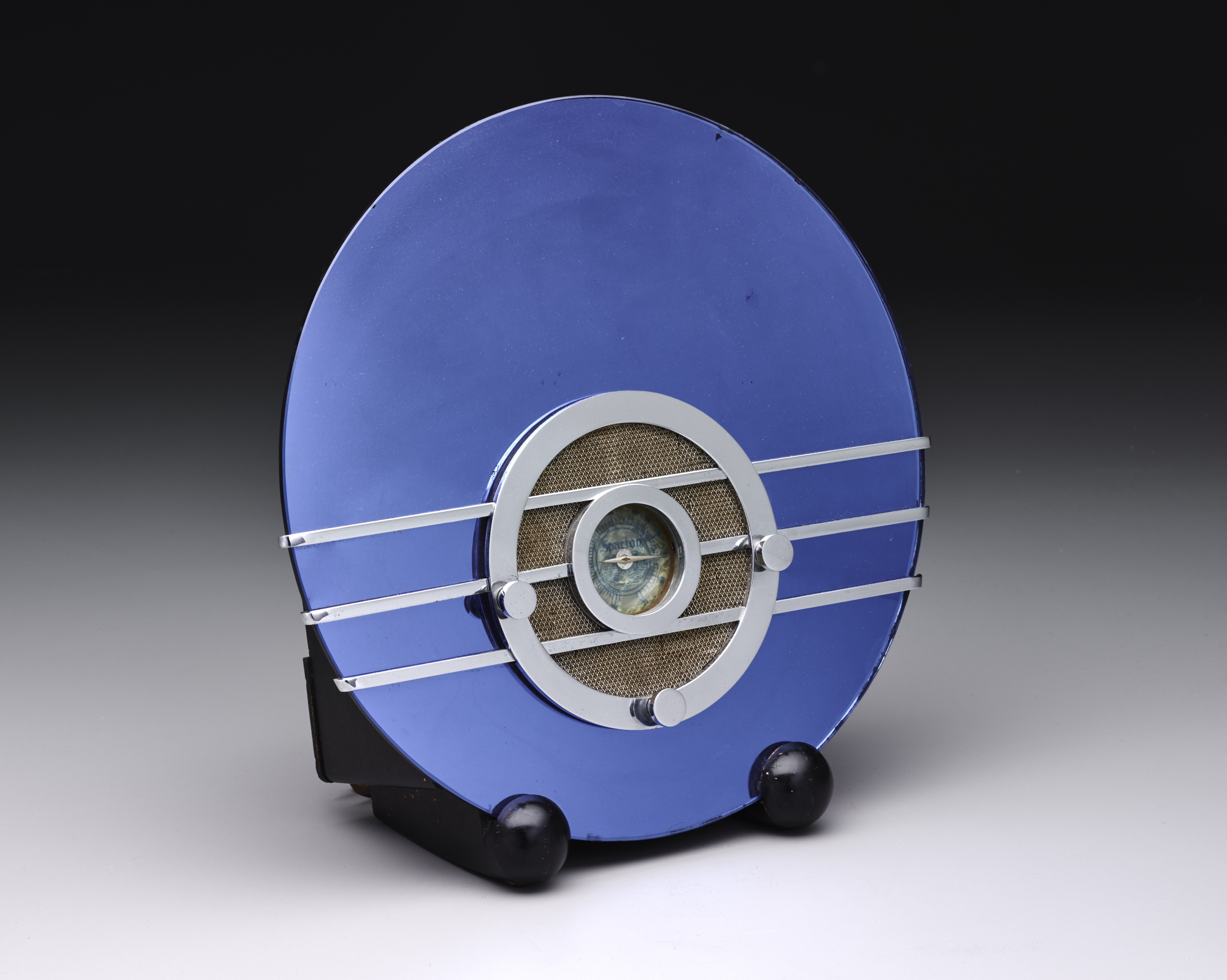

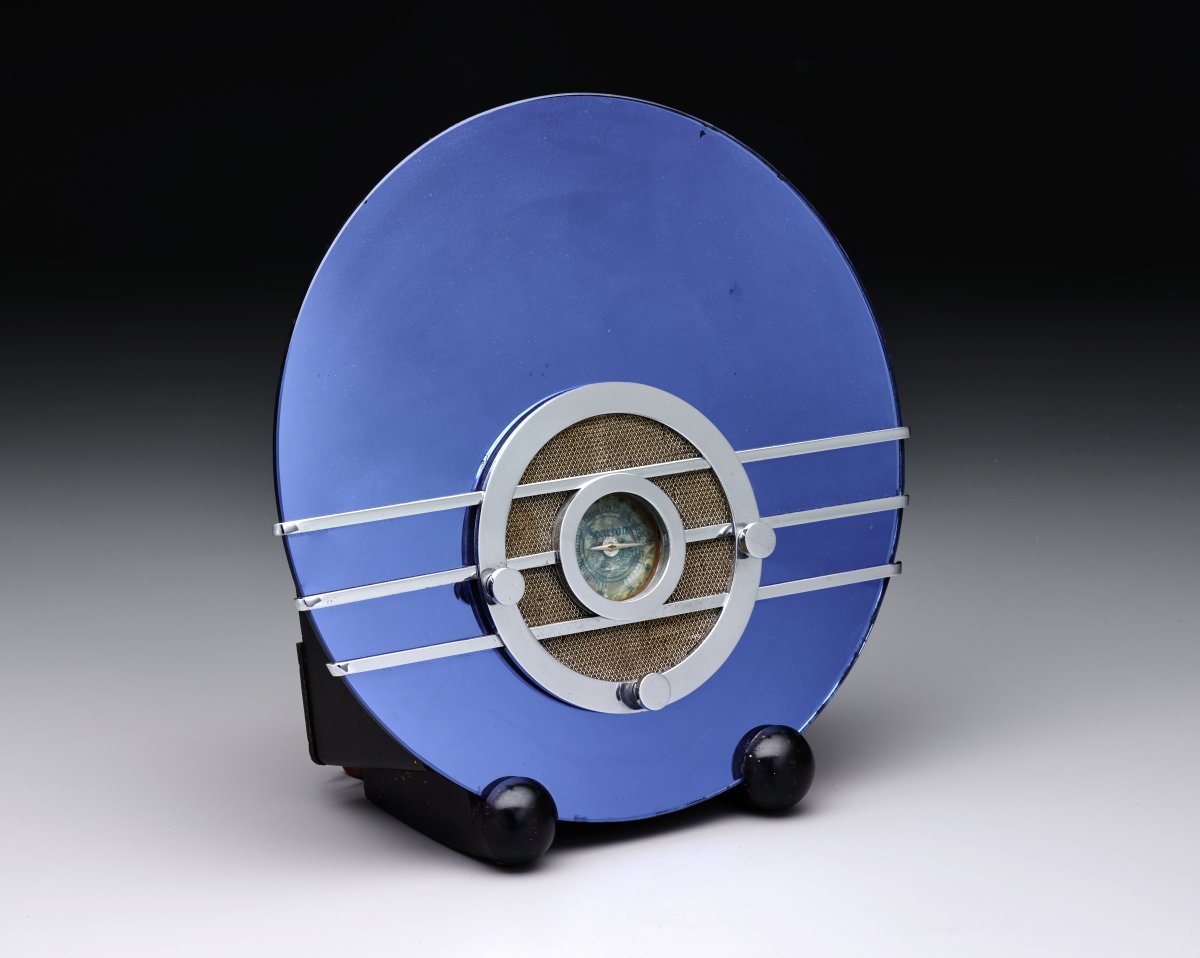

Don’t miss this “Bluebird” radio (model 566) designed by Walter Dorwin Teague and manufactured by the Sparton Corporation in 1934. The name alone embraces the notion of flight and is enhanced even further through streamlined design elements. Here, the straightforward use of circles and horizontal banding set against the plate-glass backdrop seems to mimic a single engine propeller plane’s nose and wingspan. I imagine a plane flying gracefully through the clear blue open sky, transporting the avid listener to new destinations through the magic of radio.

- Walter Dorwin Teague, “Bluebird” radio, 1934, Dallas Museum of Art, bequest of Sonny Burt, Dallas, 2014.60.4

- U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation photo no. 1996.253.879

To learn more about how the Machine Age influenced art and design in America, visit the Dallas Museum of Art’s upcoming exhibition Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art, which will open to the public on September 16.

Jennifer Bartsch-Allen is a Digital Collections Content Coordinator at the DMA.

(

(