For the past few months, Japanese sculptor Nobuo Sekine’s (b. 1942) works have been on view in the Marguerite and Robert Hoffman Galleries. For those of you who haven’t seen them yet, or are still wondering what these works are all about, this blog post is for you.

For the past few months, Japanese sculptor Nobuo Sekine’s (b. 1942) works have been on view in the Marguerite and Robert Hoffman Galleries. For those of you who haven’t seen them yet, or are still wondering what these works are all about, this blog post is for you.

Phase No. 10 (1968), Phase of Nothingness-Water (1969/2005), and Phase of Nothingness-Cloth and Stone (1970/1994) were originally created in the late 1960s, and what they have in common is the word “phase” in their title. In order to understand these works better, let’s first talk briefly about global art trends in the late 1960s and then explore the idea of “phase” that so interested Sekine.

In the early 1960s, artists such as Richard Serra, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris made a clear shift away from the gestural quality of abstract expressionism (Jackson Pollock) and embraced a more minimal aesthetic. Minimalist art was intended to discard the emotionality of the past along with all non-essential formal elements related to the art object. The resulting work took shape as hard-edge geometric volumes created with industrial materials that showed little-to-no evidence of the artist’s hand in its making. As minimal sculpture evolved, artists in the late 1960s began moving outside the white cube of the gallery and museum space to create large-scale outdoor works that used the earth itself as the medium. Known as Land Art, this movement was closely associated with the work of Robert Smithson, Michael Heitzer, and others. It is within this transitional moment between minimalism and Land Art that the work of Sekine Nobuo and the Mono-ha movement in Japan came into being.

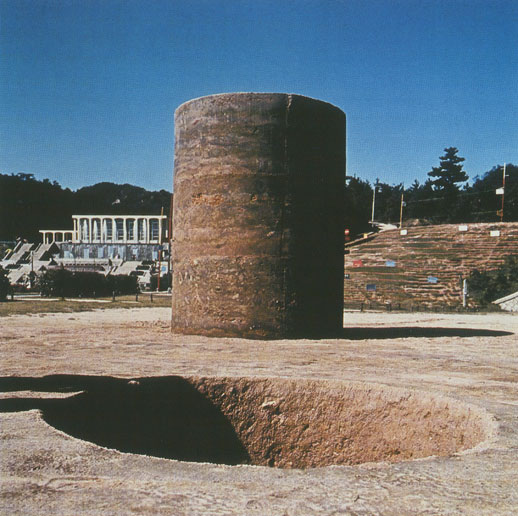

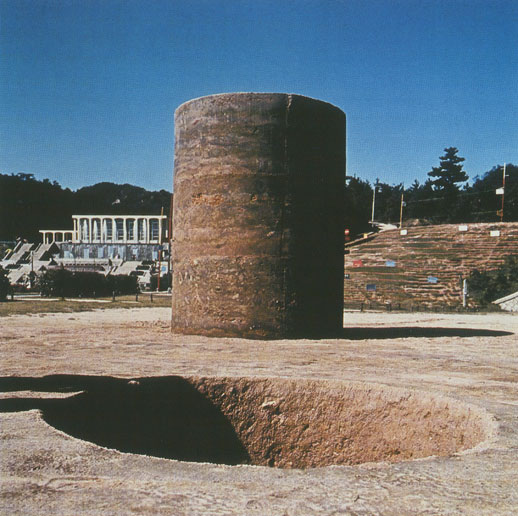

Phase Mother Earth (1968/2012) (Photo courtesy of artspacetokyo.com)

The term Mono-ha (meaning “School of Things”) encompassed a variety of different forms and approaches, but at its core the short-lived movement explored the encounter between natural and industrial objects. Using natural materials such as stone, wood, and cotton in their unadulterated states, in conjunction with wire, light bulbs, glass, and steel plates, the work of Mono-ha artists presented objects “just as they are,” with the hope of bridging the gap between the human mind and the material world.

The tenets of Mono-ha are most clearly embodied in Nobuo Sekine’s famous outdoor sculpture Phase Mother Earth (1968/2012). Often cited as the beginning of the Mono-ha movement, Sekine’s sculpture consists of a 2.2 meter-tall cylinder of earth positioned beside a hole of the exact same dimensions. While clearly in dialogue with other American and European Land Art of the time, the modest scale of Sekine’s work invites the viewer to experience the earth simply as earth rather than as a grand artistic gesture writ large across the landscape.

Phase No. 10, Nobuo Sekine, 1968, Steel, lacquer, and paint, The Rachofsky Collection and the Dallas Museum of Art through the DMA/amfAR Benefit Auction Fund

Sekine’s Phase-Mother Earth is closely related to the artist’s previous sculptures exploring the mathematical field of topology. Topology is a field of spatial geometry in which space and materials are considered malleable and can undergo countless transformations from one “phase” (state) to another without adding or subtracting from the original form/materials. In Sekine’s words, “a certain form can be transformed continually by methods such as twisting, stretching, condensing, until it is transformed into another.” This idea of manipulating form and space can be seen in Sekine’s work Phase No. 10 (1968) currently on view at the DMA. This wall-mounted sculpture closely resembles a Mobius strip, and when viewed head-on it appears to be a flat, curvilinear design, but when viewed at an angle the sculpture juts out from the wall, creating an optical illusion.

Phase of Nothingness—Water, Nobuo Sekine, 1969/2005, Steel, lacquer, and water, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA/amfAR Benefit Auction Fund

The work Phase of Nothingness—Water (1968) continues Sekine’s engagement with topology. To illustrate these ideas, the artist juxtaposed two equivalent shapes—a cylinder and a rectangle—both containing the same volume of water. At first glance, it doesn’t appear that the shallow rectangular tank and the tall cylindrical tank both hold the exact same amount of water. Similar to his earlier outdoor sculpture Phase—Mother Earth, this work attempts to depict a sense of equivalence and emphasizes the continuity of form and material. These two shapes are not meant to be seen as opposites but as equals. As Sekine explains, “[T]he mass of the universe neither increases nor decreases. This is the universe of eternal sameness. When one becomes aware of this, then the futility of modern concepts of creation can be realized.”

I hope this blog helps explain some of the fascinating (and at times complicated) ideas that inform Sekine’s sculpture. The exhibition closes Sunday, so plan your visit to the DMA before it’s too late!

Gabriel Ritter is The Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art at the Dallas Museum of Art.