For many artists a picture was not finished when the paint had dried and the varnish was applied. The culminating step was framing the artwork. Only then was the project complete. Traditionally the artist had many options. He could choose a stock frame from a local cabinetmaker, or make a thoughtful selection from a skilled framer. Artists often possessed such a keen interest to frame a painting in a manner that perfectly complemented it that they designed their own.

The 18th-century British portrait painter George Romney (1734-1802) routinely joined forces with his preferred London framer William Saunders to produce frames of the artist’s design. Frame historians have studied Saunders’ detailed ledgers that record many of these collaborations. Romney’s decorative concepts coupled with Saunders carving expertise resulted in several exquisite frames. Regrettably, as a painting changed hands the new owner would often reframe it to suit prevailing tastes or to match the room where the artwork hung.

This may have been the fate of the original frame that once surrounded Romney’s Young Man with a Flute, which is now on view in the DMA’s European Galleries. Until recently, a simple wooden frame adorned with a gilt sight edge (the part of the frame closest to the canvas) surrounded the painting. That frame was more in keeping with the sparse ones typically used by artists working in colonial America.

Wishing to restore the painting to Romney’s well-documented vision for his completed works, the Museum recently purchased a frame from a London dealer with an expertise in the artist’s designs. Now a “Romney Style” frame surrounds the painting. It is a faithful reproduction of the artist’s 18th-century original. The archetype became synonymous with the painter thus earning its eponymous name.

The approximately four-inch-wide burnished gilt neoclassical frame draws the viewer’s eye into the portrait. Its decorative elements include a rope-twist back molding, superbly carved gadrooning that traverses the circumference on the outside rim, a plain frieze, a small bead course, and a delicately reeded sight edge. The reproduction “Romney Style” frame harmonizes with the painting in a manner unrivaled by its wooden unornamented predecessor.

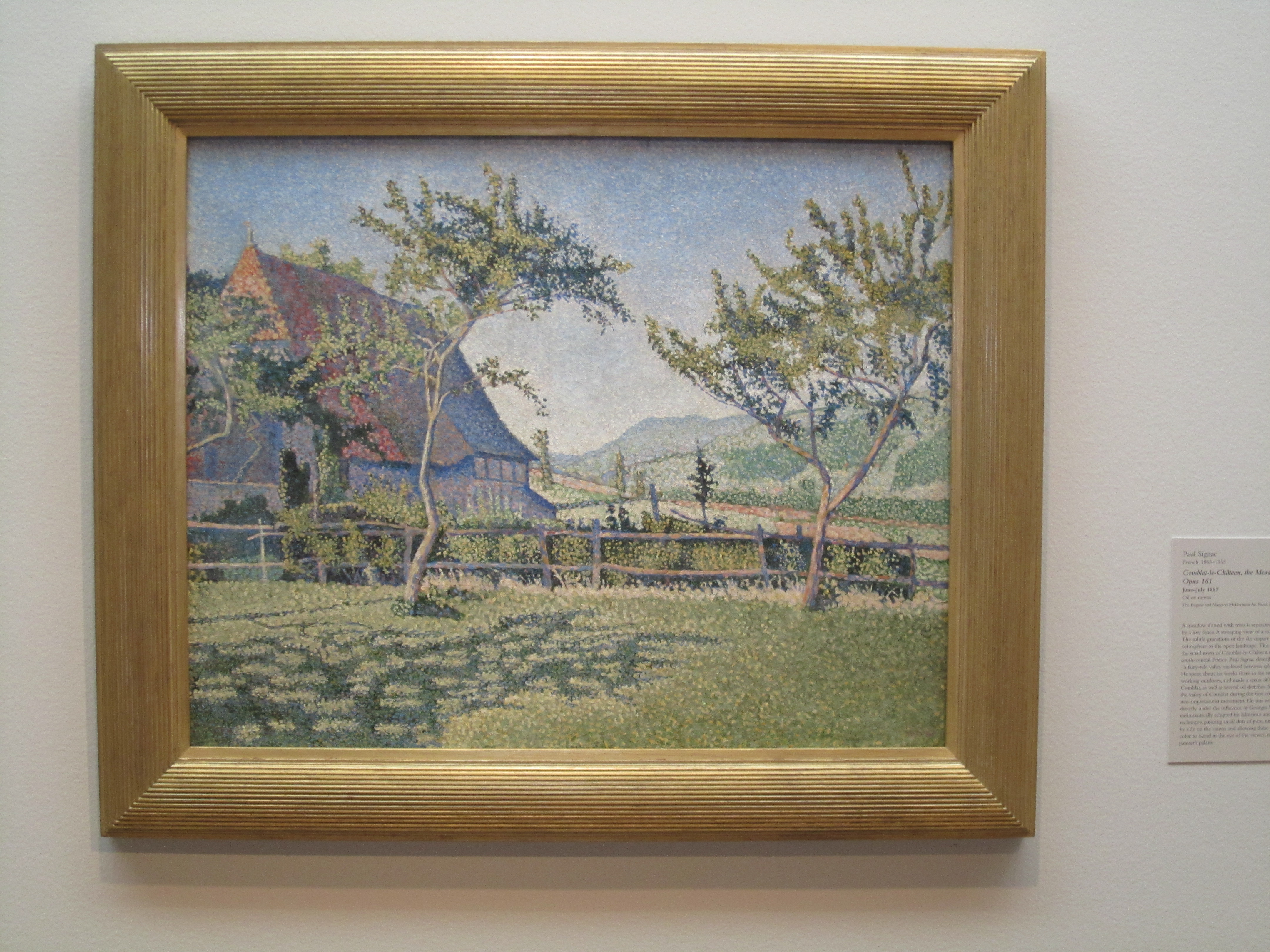

Compared to Romney, there are scant extant records of the frame choices made by the 19th-century artist Paul Signac (1863-1935). Last year, when the DMA acquired the French artist’s Comblat-le-Château, Le pré, it had a Régence Style frame that was popular very early in the 18th century.

Its decorative components included a course of cross-hatching and punch work covering the entire frame. A fussy pattern of shells, fans, palmettes, C-scrolls, and foliage ornamented the center rails and corners, while a linen liner at the sight edge completed the overall design scheme. Although a lovely frame, it is not the prototypical choice made by a post-impressionist artist who worked in the wake of the pioneering painter Edgar Degas (1834-1917). Not only was Degas enormously influential to art history but he also revolutionized frame design. In fact, he believed that it was an artist’s duty to see his pictures properly framed. Earlier this year, the DMA heeded Degas’s mandate and purchased a new frame for its Signac.

The picture’s new frame is a reproduction based on one of Degas’s most inventive designs. It features a lightly rounded profile embellished with rows of thin parallel grooves. The frame’s roundedness and fine fluting echo Degas’s “cockscomb” pattern, which he softly gilded but rarely burnished. Because of its shape, some call this format a “cushion” molding. The frame’s innovative streamlined repetitive forms do not compete with Signac’s lovely painting; rather their simplicity harmonizes with the picture to enhance it. While these before-and-after photographs illustrate the difference a frame can make, they pale when compared to seeing firsthand each striking painting now with its stylistically appropriate frame. On your next visit to the DMA, come view these superb frames and the paintings they surround.

Martha MacLeod is the Curatorial Administrative Assistant in the European and American Art Department at the Dallas Museum of Art.