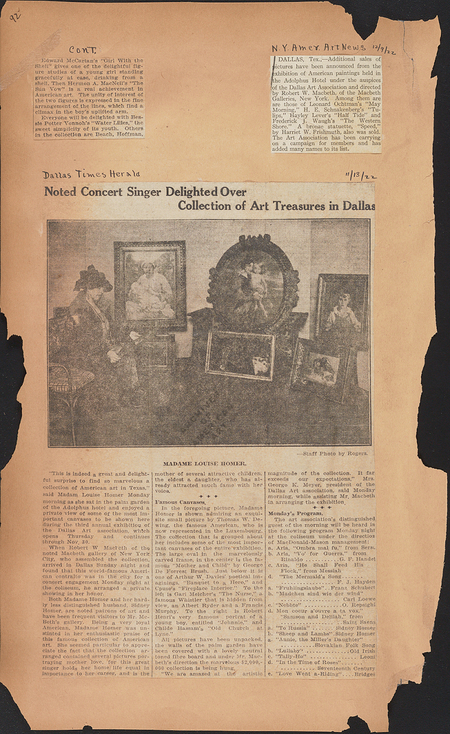

This photo has been popular in Museum histories for a long time. It was used in the book Seventy-Five Years of Art in Dallas: The History of the Dallas Art Association and the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (1978) by Jerry Bywaters; the 90th Anniversary Timeline; and the 2003 Centennial history exhibition, and she has always been identified as a “Dallas arts patroness.”

The panel of the image from the 2003 exhibition currently hangs in the Archives. When curators come down, they always search to see if any of the paintings in the photo are part of the collection, though nothing is familiar. I have always thought that the paintings in the photo were from one of the Dallas Art Association’s (DAA) early annual exhibitions, but I had no idea which one. Then I came across a memo that identified the painting at her feet as an Albert Pinkham Ryder work that was to be part of the 2002 Gilded Age exhibition touring from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I was thrilled with this clue because now I could search the digitized exhibition catalogues and figure out the exhibition to at least date the photo.

It turns out that the painting in the photo was not the one in the exhibition, but a different Ryder painting of a ship at sea. Using books on Ryder from the library, I was able to identify the work as Ryder’s painting The Waste of Waters is Their Field, now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847-1917). The Waste of Waters is Their Field, early 1880s. Oil on panel, 11 5/16 x 12 in. (28.8 x 30.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, John B. Woodward Memorial Fund, 14.556 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 14.556_SL1.jpg)

With the new information, I could search for this painting in the digitized catalogues. I identified the exhibition as being from the Third Annual Exhibition: American Art from the Days of the Colonists to Now, held by the DAA at the Adolphus Hotel’s Palm Garden, November 16-30, 1922.

By using the exhibition checklist in the catalogue, with a bit of library and internet searching, I was able to definitively identify two of the other works in the photo, with educated guesses on two others. The oval painting is Mother and Child: A Modern Madonna by George de Forest Brush, also in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

George de Forest Brush (American, 1855-1941). Mother and Child: A Modern Madonna, 1919. Oil on canvas, 43 1/2 x 35 5/8 in. (110.5 x 90.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Museum Collection Fund and by subscription, 19.93 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 19.93_transp3194.jpg)

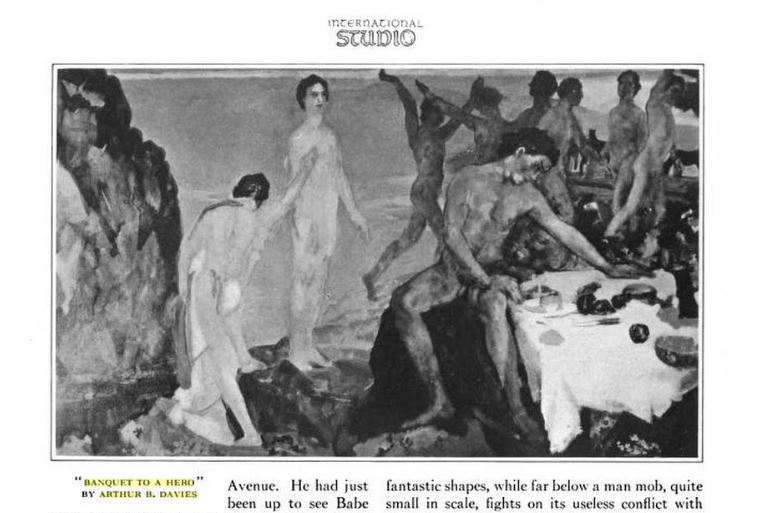

The painting leaning on the settee below it is Arthur B. Davies’ Banquet to a Hero, identified from the article “Davies the Absolute” by F. Newlin Price in the June 1922 issue of International Studio.

Now I had the exhibition and date, but I still had no idea who the “patroness” was. Time for a different tactic.

The exhibition was curated for the DAA by Robert MacBeth of the MacBeth Gallery, and being a good archivist, I went searching for records from the gallery in hopes of finding a new clue. I found the records at the Archives of American Art. Using the digitized scrapbooks from the MacBeth Gallery Records, I found a whole section of news clippings related to the Dallas exhibition in the 1922 scrapbook.

I was flipping through these pages, when all of a sudden, there was my patroness photo!

The photo illustrated the November 13, 1922, Dallas Times Herald article “Noted Concert Singer Delighted Over Collection of Art Treasures in Dallas.” The concert singer is Madame Louise Homer. She knew Robert MacBeth from his New York gallery and he invited her to preview the exhibition while in Dallas for a performance at the coliseum. So, the woman in the photo is technically an art patroness, just not a Dallas one.

The other paintings in the photo are also identified in the article, and I am happy to say that my educated guesses were correct.

This was a fun research project to work on, and happily it resulted in definitive answers and a mystery solved—if only they were all like that.

Hillary Bober is the Archivist at the Dallas Museum of Art.