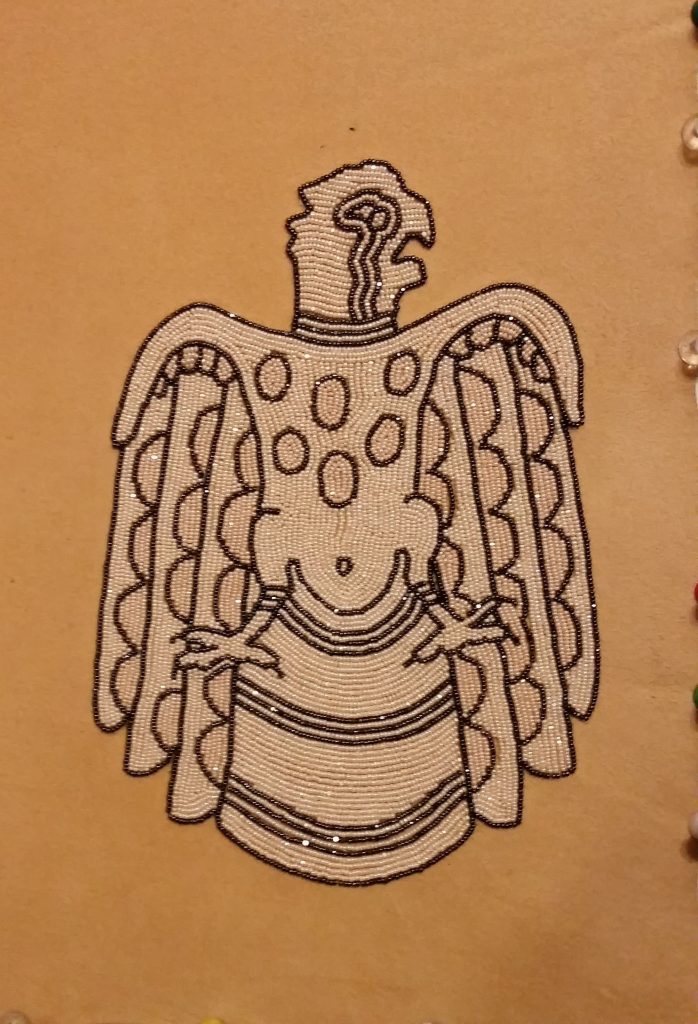

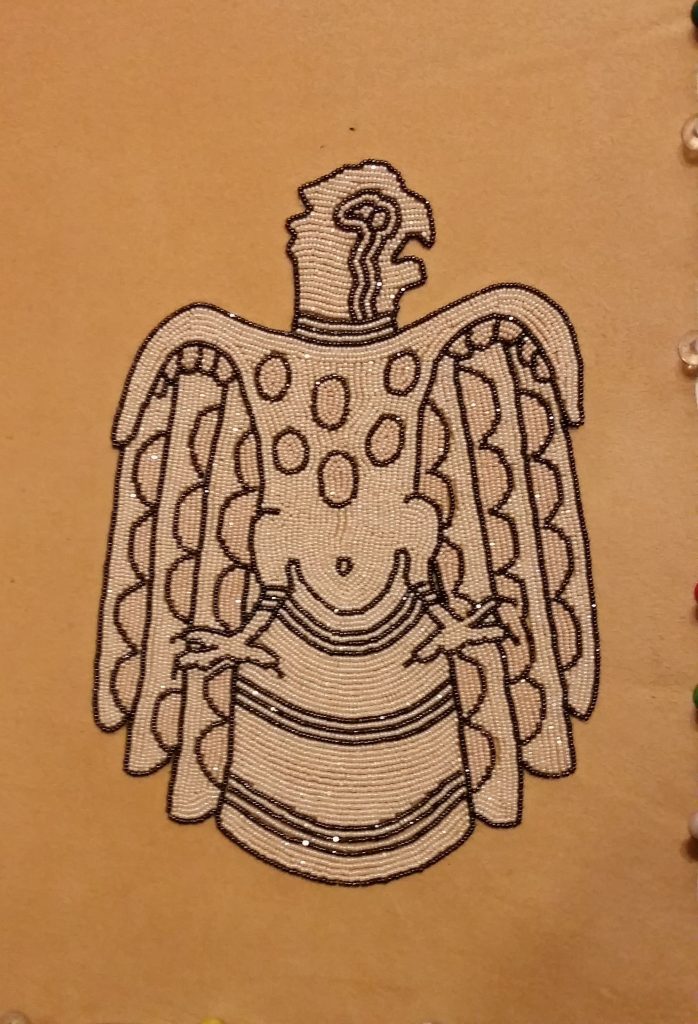

Yonavea Hawkins is an artist who creates intricate beadwork for Native American and Caddo cultural items. We are delighted to have her participate in the upcoming Late Night celebrating the new exhibition Spirit Lodge: Mississippian Art from Spiro, during which she will showcase several of her pieces and talk about her process and the connection between traditional and contemporary beadworking. Read our special Q&A with her to learn more about her practice ahead of the event on March 25!

How did you begin creating art?

As a child I was always drawing and painting, with art class in school being my favorite subject, then to obtaining a fine arts degree from Oklahoma City University and started working as a graphic designer. Eventually my 8 to 5 creative jobs morphed into print quality control with organized paperwork of meeting deadlines and budgets. Then and now with a full-time job, evenings and weekends are my creative times. Working from a small desk, my present work evolved from learning to sew and bead to make Caddo regalia for myself, my children, and then Native American regalia for others. Now I create a variety of bead work, cultural items, or diverse art with different beading techniques for juried art markets with competitions. Changing from pencil and paint to beads and buckskin became new mediums to work in and another way to express myself creatively.

The words “contemporary” and “traditional” carry a lot of weight when describing Indigenous arts. Where do you situate your work?

For my work it’s a combination of contemporary and traditional because of the materials used and the design elements, to the construction of the finished work. Contemporary because of the use of the current Charlotte bead colors and todays materials to bead on. Traditional, when I find the materials online to buy as I am an urban Native American without access to harvest and collect traditional materials once used. The use of glass bead work starts from European contact as beads, wool and silk were trade goods to Indigenous peoples, and these trade goods became traditional for some Indigenous peoples. Beading techniques developed for using trade beads and used today holds the traditional look, but in contemporary colors and designs, unless you find a stash of antique beads.

Tell us about some of the work you’re showing at DMA’s Late Night.

Several years back, a collector of my art told me that my beadwork was “Wearable Art”. As such a great deal of my work created for art markets are bracelet cuffs, contemporary beaded belts, belt buckles, hair barrettes, necklaces, and hatbands. After attending an art market, I never know what work will sell out and what I will be creating next, but I plan to show a variety of pieces mentioned earlier. I will also show cultural items that have won awards at art markets such as moccasins, turtle shell purses, bandolier bags, and pipe bags.

________

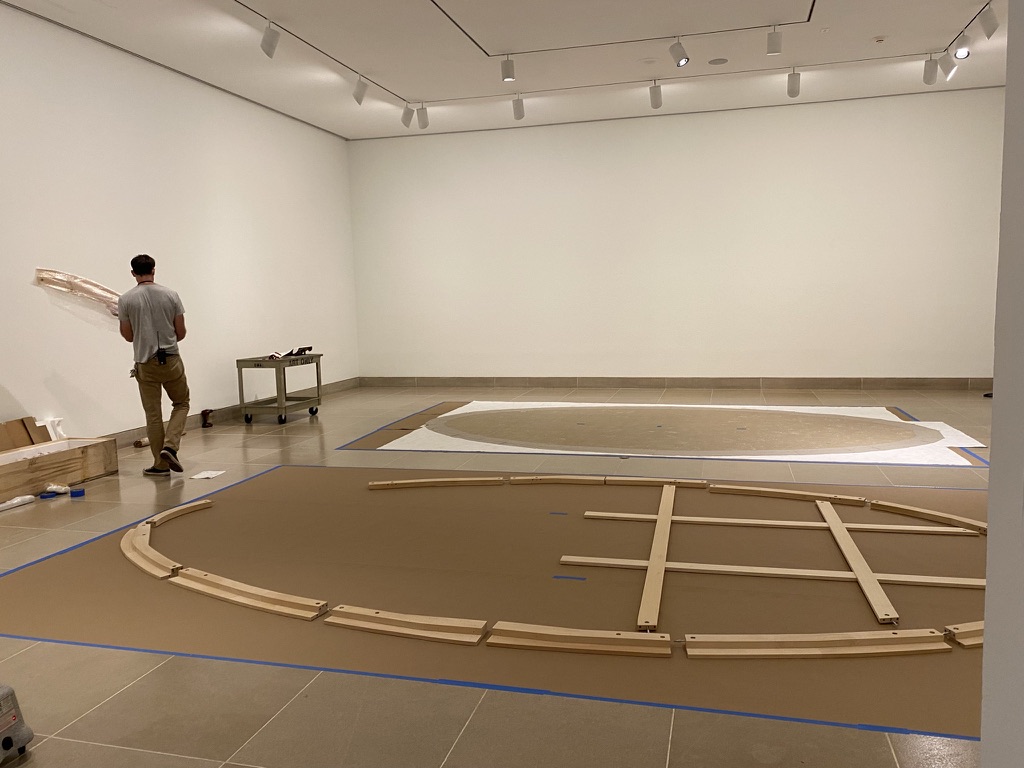

You can find out more about Yonavea Hawkins in this recent artist interview. Don’t miss out on our Late Night celebration on March 25, featuring artist demonstrations, art making, performances, films, and talks about the exhibition Spirit Lodge: Mississippian Art from Spiro, and more! Get tickets here.