Henry Moore’s Two Piece Reclining Figure, No. 3 has greeted visitors at the Museum’s North Entrance for many years. Last week, Moore’s sculpture moved to a new home on the south side of the building, where it will welcome visitors into the Sculpture Garden. The move involved a lot of planning, and many precautions were in place to move the 2,200-pound bronze sculpture. Follow the sculpture’s journey below:

Archive for the 'Collections' Category

Moore on the Move

Published July 27, 2015 Behind-the-Scenes , Collections ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Henry Moore, North Entrance

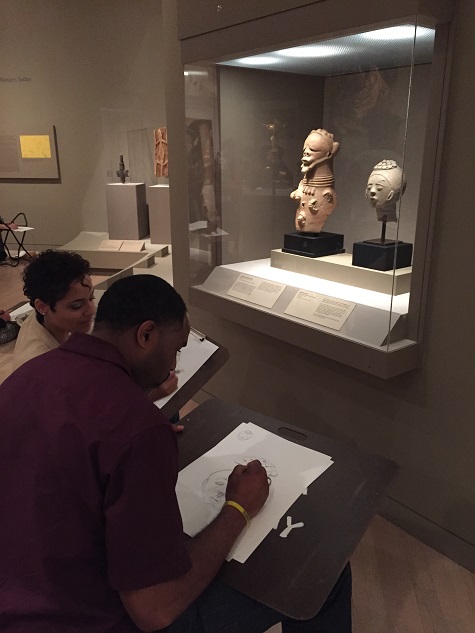

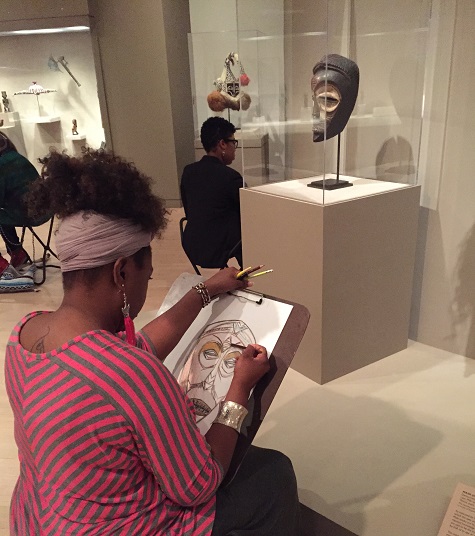

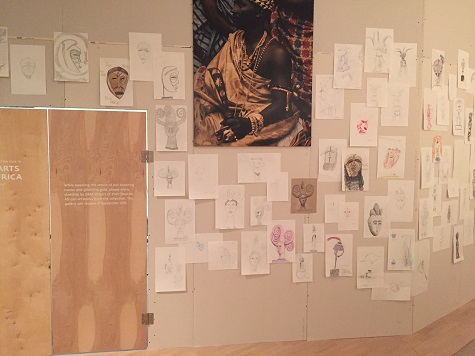

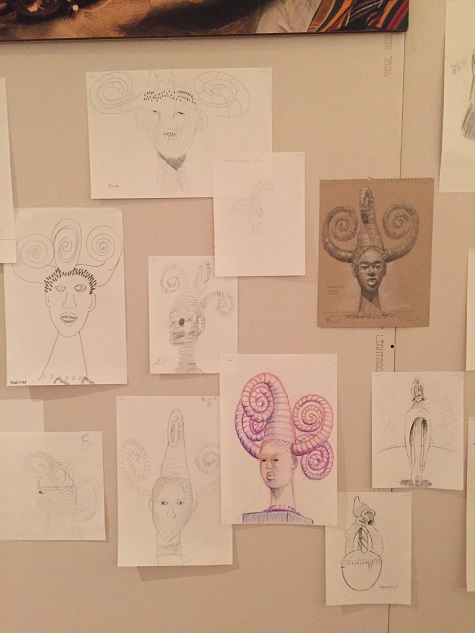

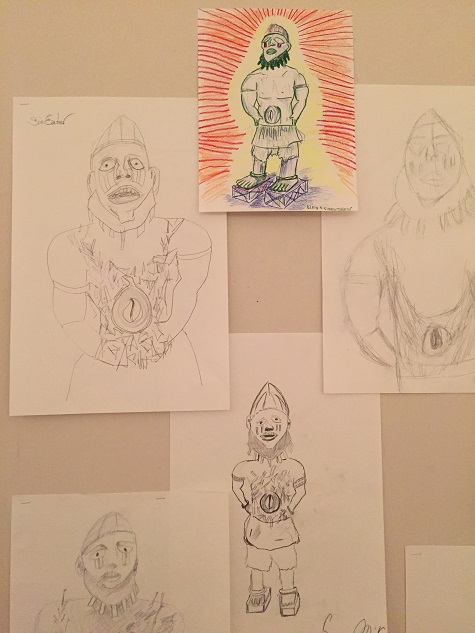

African Art Sketching Party

Published July 22, 2015 Collections , Late Nights ClosedTags: Africa, African Art, Arts of Africa, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, sketching, visitor voices

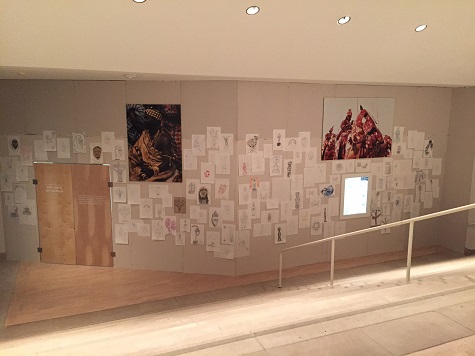

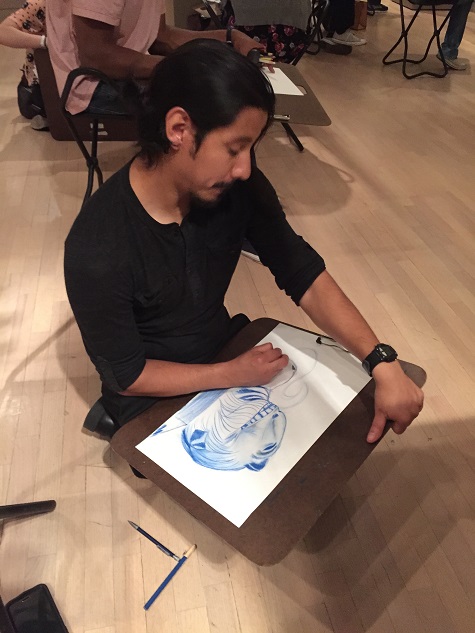

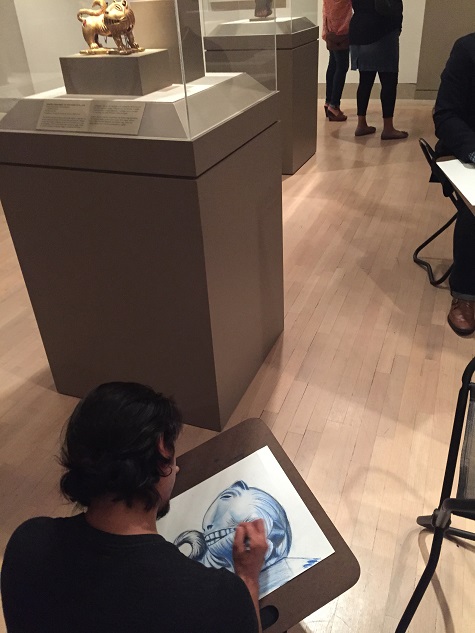

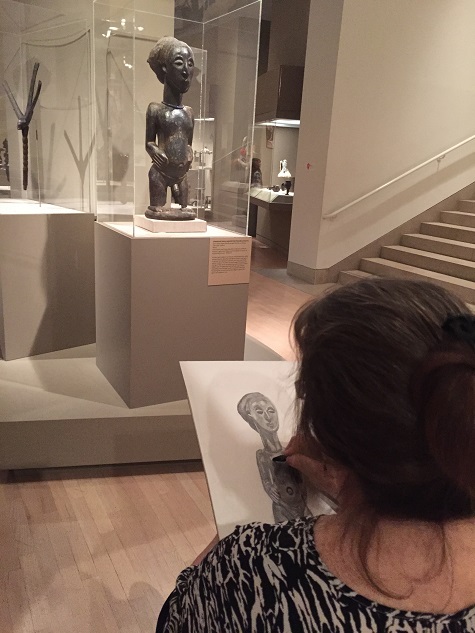

Just before the Arts of Africa gallery closed for reinstallation in May, the DMA invited the public to a Late Night African Art Sketching Party. Over 100 sketches of visitors’ favorite African artworks were gathered during the party. It was an opportunity to tap into the creativity and perspectives of DMA visitors. Sketching is a fun way to slow down, look closely, and discover something new about an artwork.

Visitors’ drawings are on view on a temporary wall on Level 3 in the Museum. Come for a visit before August 30 to see this installation of sketches and experience the DMA’s African art collection as seen through the eyes of another.

Nicole Stutzman Forbes is the Chair of Learning Initiatives and Dallas Museum of Art League Director of Education at the DMA.

After Hours

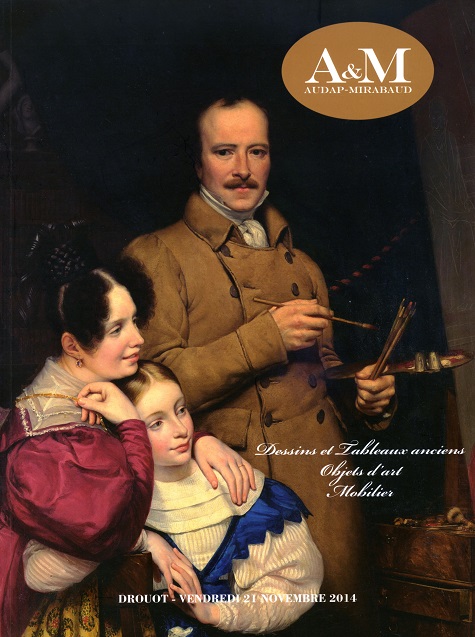

Published July 15, 2015 Behind-the-Scenes , Collections , Curatorial , European Art ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Paul Claude-Michel Carpentier

Have you ever wondered what museum curators do to relax and unwind at the end of their day? For Olivier Meslay, the DMA’s Associate Director of Curatorial Affairs, one of his favorite things is to look through online versions of auction house and gallery catalogs. What seems like a bit of a “busman’s holiday” worked to our advantage a few months ago.

It all started on a stormy night early last November when he clicked on the website for the Parisian auction house Audap & Mirabaud. On their homepage was the lovely self-portrait by Paul Claude-Michel Carpentier (1787-1877), a lesser-known French painter, sculptor, and engraver who had exhibited at the Salon between 1817 and 1838.

The painting that caught Olivier’s attention is signed and dated 1833, and Carpentier exhibited it at the Salon the following year. For some time, the DMA had been seeking to purchase a large-scale 19th-century Salon portrait, and this one fit the bill. It was to be auctioned in Paris on November 21, and, as it happened, Olivier would be in France on the day of the sale, but not in Paris. Luckily, he had plans to be in the glorious city a few days beforehand and found an occasion to examine the painting.

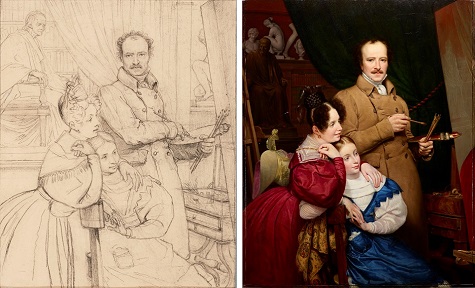

Paul Claude-Michel Carpentier, Self-portrait of the artist and his family in his studio, 1833, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, Mrs. John B. O’Hara Fund, 2014.38.FA

It was as impressive as he had hoped, and so he registered to bid. The only remaining problem was that at the precise time of the sale he was to be at a conference in a city four hours away. About mid-morning on November 21, he discreetly slipped out of his meeting for a few minutes to bid by telephone on the artwork. To our great fortune, he was the high bidder. All of his maneuverings were worthwhile.

When he returned to Paris a few days later, to his great surprise, he learned from an agent with Audap & Mirabaud that a small, fully realized preliminary drawing of the portrait had become available. He bought it on the spot.

(left) Study for Self-portrait of the artist and his family in his studio, c. 1833, pencil on paper, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of Olivier Meslay, 2015.20.FA; (right) Paul Claude-Michel Carpentier, Self-portrait of the artist and his family in his studio, 1833, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, Mrs. John B. O’Hara Fund, 2014.38.FA

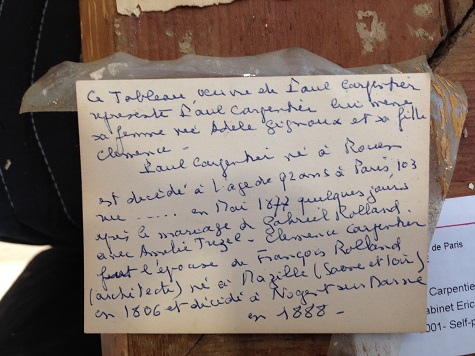

Another exciting aspect of these purchases is that it presented us with an opportunity to learn about Carpentier’s life. One of the most immediate revelations happened shortly after the painting arrived at the DMA. Much to our surprise, we discovered a small slip of paper affixed to the back of the frame. On the very old sheet were handwritten details (in French, of course) about Carpentier; his wife, Adèle; and daughter Clémence.

Slip of paper affixed to upper rail of the back of the frame with details of the artist’s immediate family and descendants.

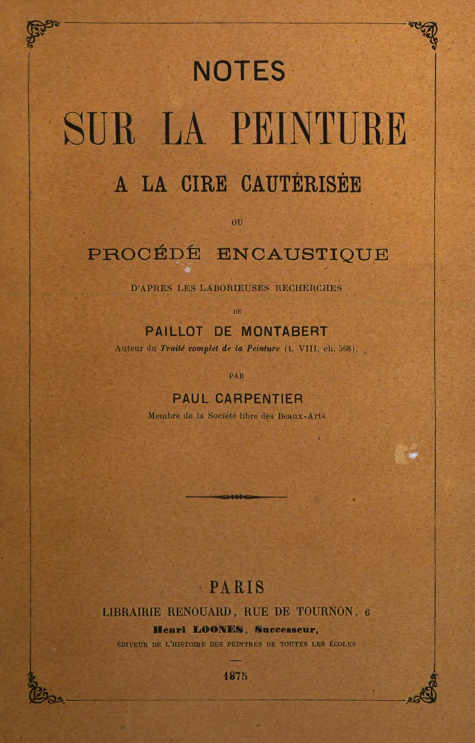

As our research about Carpentier progressed, we unearthed some very intriguing discoveries. While he was quite active in the Society des Beaux-Arts, advocating for various artistic mutual aid societies, he was also an accomplished theoretician and technician of encaustic painting. The ancient process of adding pigment to melted beeswax, which dates back to antiquity, fascinated Carpentier throughout his lifetime and culminated in his authoring a detailed treatise about the technique that artists still consult today.

Most interestingly, we discovered that one of his closest friends was Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851), the French artist and photographer recognized for inventing the eponymous process of photography. As a testament to their mutual admiration, Carpentier made a painting and bust of his good friend, but more importantly, in 1855 he wrote a monograph about Daguerre that to this day remains the single greatest firsthand contemporary account on the birth of photography.

Knowing more about Carpentier, and turning back to his self-portrait, we see that in it he brought together people and things that held an important place in his life. While we discovered valuable information about the painting and artist, we also learned that we all gain when our Associate Director of Curatorial Affairs relaxes at the end of a busy day by surfing the Web. Visit the newly conserved painting in the DMA’s Level 2 European Art Galleries, included in free general admission, today!

Martha MacLeod is the Assistant to the Associate Director of Curatorial Affairs and Curatorial Administrative Assistant for the European and American Art Department at the DMA.

An Unlucky Month

Published July 13, 2015 Collections , DFW , Late Nights , Special Events ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Late Night, museum murder mystery

For the fourth year in a row, we have heard rumors that at our next Late Night on Friday, July 18, another mysterious murder will take place at the DMA! It seems like July is an unlucky month for works of art in our collection.

Last year, over two thousand visitors participated in our Museum Murder Mystery Game during Late Night! If you were one of those super sleuths, you found out that it was Emma in a Purple Dress who killed Queen Semiramis in the Chinese galleries with the Bird macaroni knife from the American galleries.

And while Emma in a Purple Dress was brought to justice, we will need your help to once again uncover the dastardly goings on at the DMA.

It will be up to our visitors to solve this fourth Museum Murder Mystery by figuring out who the murderer is, the weapon he or she used, and the room where the murder took place.

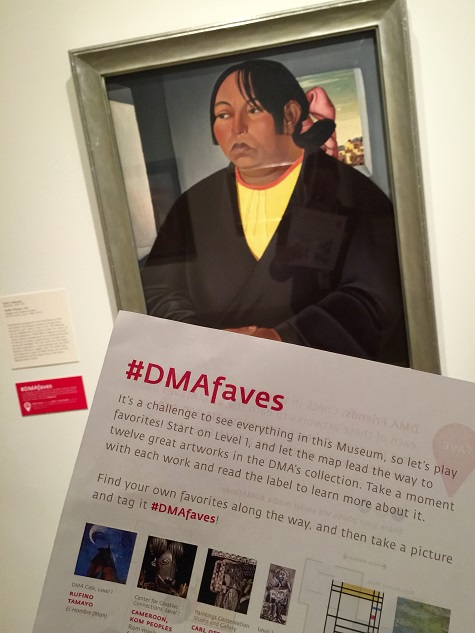

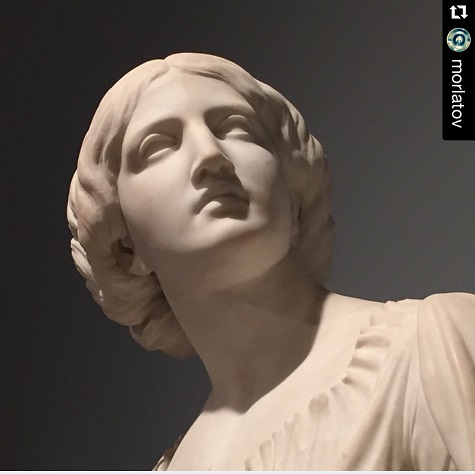

For one night only, the seven works suspected of the murder will come to life and answer your questions. Without revealing who the suspects are, as they are innocent until proven guilty, these photos will give you a clue to their identities.

In addition to the Museum Murder Mystery Game, there will be a lot more mysterious and fun things to do during the Late Night; be sure to check out the full schedule of events.

Stacey Lizotte is Head of Adult Programming and Multimedia Services at the DMA.

Let’s Play Favorites

Published July 8, 2015 Collections , DMA Friends ClosedTags: #DMAFavs, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, DMA Friends, Free, Summer

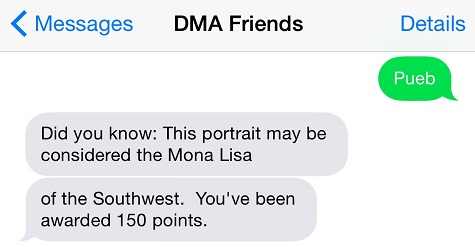

There’s a lot to see in the DMA’s collection, so this summer we made it easy for you to view a selection of our highlights. From ancient to contemporary, from paintings to masks to sculptures, our #DMAfaves will have you exploring every floor of the Museum. Grab a #DMAfaves self-guided tour at the Visitor Services Desk and hunt for our twelve #DMAfaves throughout the DMA.

- Green Tara, 18th century, Tibet, gilt copper alloy and turquoise, Dallas Museum of Art, the Cecil and Ida Green Acquisition Fund 2005.28

- Alexander Calder, Model for Flying Colors, 1973, fiberglass and acrylic paint, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Braniff International in memory of Eugene McDermott 1973.103

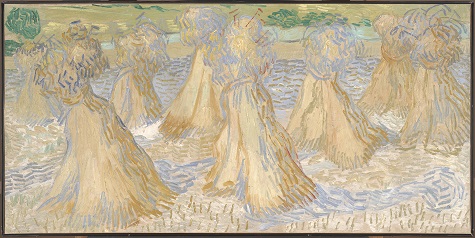

- Vincent van Gogh, Sheaves of Wheat, July 1890, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection 1985.R.80

Earn Friends points by checking in each time you find one of our #DMAfaves in the galleries. In addition to points, you’ll also receive a fact about every piece of art you find. Not familiar with our Friends program? Find out more here.

Earn the #DMAfaves Friends badge by finding all twelve!

We want to know your favorite pieces in our collection too! Take photos of your own faves, tag them with #DMAfaves, and post them to social media. We’ll share your pictures on our Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram accounts all summer long.

Paige Weaver is Marketing Manager at the DMA.

Stars and Stripes

Published July 2, 2015 Collections ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Fourth of July

This fourth of July we are celebrating the stars and stripes in the DMA collection. The DMA is open tomorrow, July 4th, and the entire weekend, so come explore the collection for free!

- Nic Nicosia, Bobby Dixon & the Texas Stars, 1986, screenprint, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Pepsi-Cola Bottling Group, Dallas, Texas © 1986 Nic Nicosia, Dallas, Texas 1986.7.4

- Sol Lewitt, Anthony Sansotta, Wall Drawing #398, 1983, drawn April 1985, color ink wash, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The 500, Inc., Mr. and Mrs. Michael J. Collins and Mr. and Mrs. James L. Stephenson, Jr. 1985.3

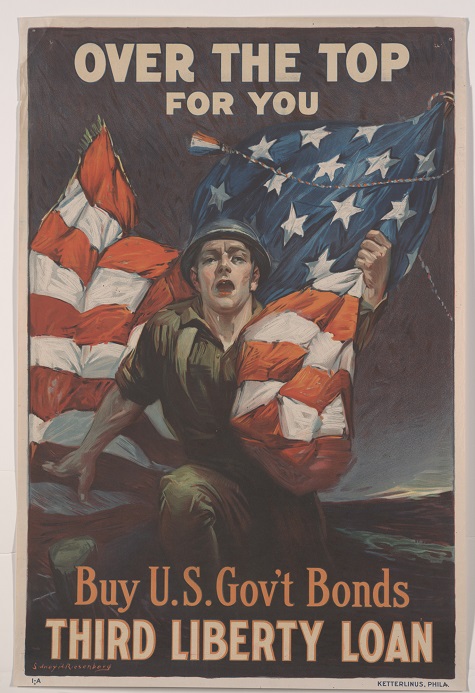

- Sidney H. Riesenberg, United States Department of the Treasury, Ketterlinus, Over the Top for You. Buy U. S. Gov’t Bonds, Third Liberty Loan, 1918, color offset lithograph, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Marcia M. Middleton in memory of Joel Middleton 1980.96

- Alexander Calder, Flying Colors ’76, 1976, color lithograph, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Braniff International, the Color Guard Employees © Estate of Alexander Calder / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 1976.25

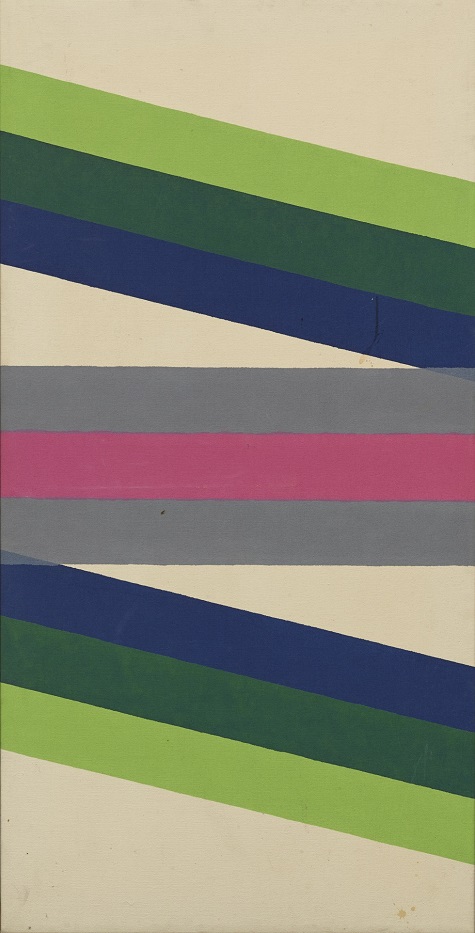

- Paul Reed, Interchange XII, 1966, acrylic on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of John W. English 1967.22

- Gerald Murphy, Razor, 1924, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of the artist

- Rufino Tamayo, El Hombre (Man) (detail), 1953, vinyl with pigment on panel, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association commission, Neiman-Marcus Company Exposition Funds 1953.22

- Alexandre Hogue, Liberators, 1943, Lithograph, Dallas Museum of Art, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Prize for Technical Excellence, Third Annual Texas Print Exhibition, 1944 © Olivia Hogue Mariño & Amalia Mariño Copyright for this work may be controlled by the artist 1943.49

- Star-shaped club head/Cabeza de porra en forma de estrella, Peru: Andean coast, A.D. 100–700, copper, Dallas Museum of Art, The Nora and John Wise Collection, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jake L. Hamon, the Eugene McDermott Family, Mr. and Mrs. Algur H. Meadows and the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, and Mr. and Mrs. John D. Murchison, 1976.W.1773

- Kenneth Noland, Shade, 1967, acrylic on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated © The estate of Kenneth Noland /VAGA, New York 1981.131

- Brice Marden, To Corfu, 1976, oil and wax on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift © 2014 Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

- Michael Bevilacqua, High-Speed Gardening (detail), 2000, acrylic on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by The Neuberger Berman Foundation 2001.61.A-B

- Robert Indiana, Hemisfair, San Antonio, 1968, poster, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Tucker Willis 1998.101

- Striped chevron bead, n.d., drawn glass, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The Dozier Foundation 1990.295.1

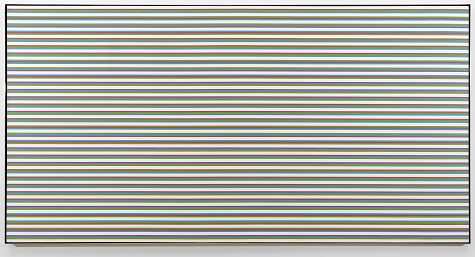

- Bridget Riley, Rise 2, 1970, acrylic on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of Mr. and Mrs. James H. Clark © 1970 Bridget Riley

Kimberly Daniell is the Manager of Communications and Public Affairs

#LoveWins

Published June 26, 2015 Collections ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Félix González-Torres, Love Wins

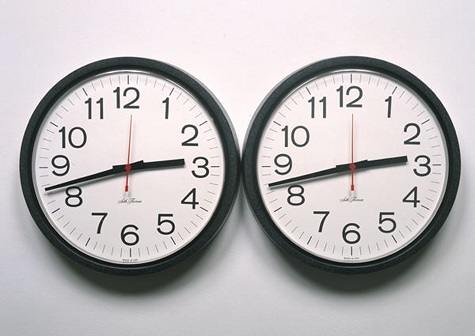

In commemoration of today’s decision we wanted to share Félix González-Torres’s work in the DMA collection Untitled (Perfect Lovers).

The date of this work corresponds to the time during which Félix González-Torres’s partner, Ross Laycock, was ill, and it embodies the tension that comes from two people living side-by-side as life moves forward to its ultimate destination. González-Torres comments: “Time is something that scares me . . . or used to. This piece I made with the two clocks was the scariest thing I have ever done. I wanted to face it. I wanted those two clocks right in front of me, ticking.”

Félix González-Torres, Untitled (Perfect Lovers), 1987-1990, wall clocks, Dallas Museum of Art, fractional gift of The Rachofsky Collection © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

Kimberly Daniell is the Manager of Communications and Public Affairs at the DMA

Dad’s Day at the DMA

Published June 19, 2015 Collections ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA. Father's Day, Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures, c. 1909, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Deaccession Funds, 1986.9

In honor of Fathers’ Day, we are showcasing artist Henry Ossawa Tanner’s tender rendering of his wife and son, whom he used as models for Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures. In addition to this painting in the DMA’s collection, another, later version is in the Des Moines Art Center. The two were based on inscribed photographs taken by Tanner of his Swedish-born wife, Jessie, and their son, Jesse; the photographs are now housed in the Tanner Papers collection at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

(Image: Jessie Olssen Tanner and Jesse Ossawa Tanner posing for Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting of Christ and his mother studying the scriptures, not after 1910. aaa.si.edu/)

Tanner painted a portrait of his own father, African Methodist Episcopal bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner (1897), now in the Baltimore Museum of Art. The Tanner family lived primarily in France, where the artist had settled in the 19th century to escape racial discrimination in America. The artist’s last years were devoted to the care and recovery of his only son, who had a nervous breakdown following his graduation from Cambridge. Jesse Tanner went on to become a successful petroleum engineer, and in the 1950s he wrote a manuscript, The Life and Works of Henry O. Tanner, dedicated to his father.

Visit Tanner’s painting, on view in the DMA’s Level 4 galleries and included in free general admission, this weekend to celebrate the dad in your life.

Reagan Duplisea is the Associate Registrar at the DMA.

Candles for Courbet

Published June 10, 2015 Collections ClosedTags: Birthday, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet was born June 10, 1819, and thus 196 years ago today the realist movement was born. The DMA is home to a number of works by the 19th-century French painter. Stop by and wish this great artist happy birthday by visiting two of his works currently on view, Fox in the Snow on Level 2 and Still Life with Apples, Pear, and Pomegranates in the Wendy and Emery Reves Collection.

Gustave Courbet, Fox in the Snow, 1860, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, Mrs. John B. O’Hara Fund, 1979.7.FA

Gustave Courbet, Still Life with Apples, Pear, and Pomegranates, 1871 or 1872, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection, 1985.R.18

Kimberly Daniell is the Manager of Communications and Public Affairs at the DMA.

Golden Glaze

Published June 5, 2015 Behind-the-Scenes , Collections ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, donut, doughnut, Hypnotic Donuts, National Doughnut Day

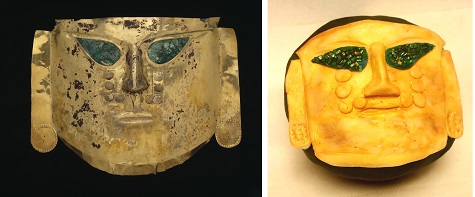

Today is one of the tastiest holidays all year, National Doughnut Day. Last year, we had so much fun seeing one of our paintings transformed into a ring of delicious art that we teamed up with Hypnotic Donuts for round two. James, the owner of the popular North Texas doughnut shop, and his head designer, Chrysta, explored the four floors of art in the Museum and were drawn to our pre-Columbian gallery and the gold Sicán ceremonial mask.

Chrysta sculpted the fondant by hand and made each individual piece of the ceremonial mask.The pieces were then assembled and painted gold, and darker color was added for shadowing. For the eyes, she died the fondant an emerald hue and rolled it in sprinkles. The “paint” was created by mixing food coloring, sprinkles, and sugars.

This pastry fit for the gallery walls will be “on view only” at Hypnotic Donuts today during business hours. Head to Hypnotic Donuts in East Dallas to see the artistic doughnut, and stop by the DMA to see the work that inspired this year’s sweet masterpiece.

Kimberly Daniell is the Manager of Communications and Public Affairs at the DMA.