Recently we welcomed Elena Torok to the DMA’s Conservation Team! She joins us in the new role of Assistant Conservator of Objects. With over 24,000 objects in our encyclopedic collection, an active acquisition program, busy exhibition calendar, and increasing analytical/research needs, this additional staff member will assist with the growing demands on conservation.

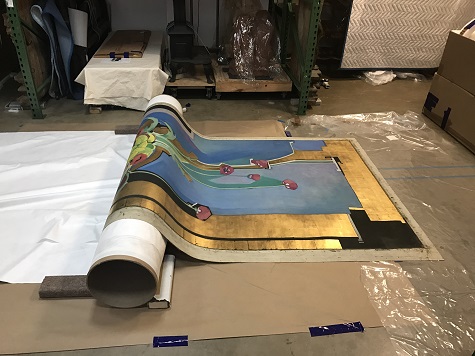

She will work closely with the Collections and Exhibition Teams – and looks forward to sharing her holistic and scientific knowledge of materials with the larger team – creating a care plan for the collections. She will dive immediately into the treatments of several objects for upcoming rotations.

Below, Elena answers a few brief questions for Uncrated to introduce her to you. Welcome Elena!

Before joining us at the DMA, where did you work?

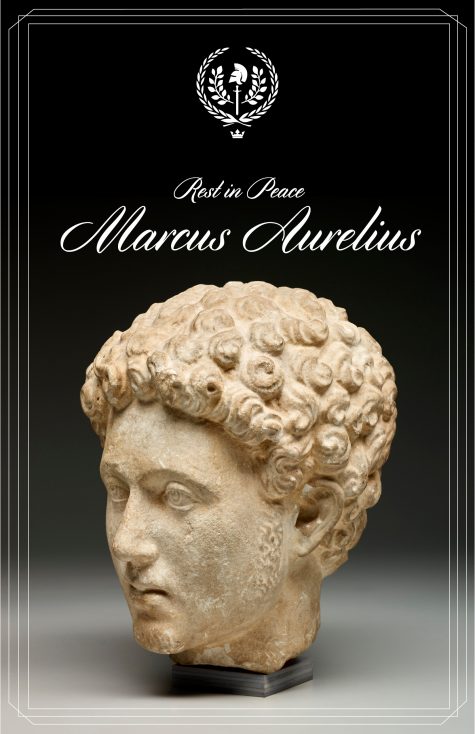

Before joining the DMA, I worked for just over four years as a conservator at the Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG) in New Haven, CT. Most recently, I worked on YUAG’s large-scale storage move of 35,000 objects to the new Margaret and Angus Wurtele Collection Studies Center, a brand new visible study and storage center at Yale’s West Campus. I also assisted with the treatment and scientific analysis of a range of different types of objects (including decorative arts, modern and contemporary sculpture, and archaeological materials).

Prior to my time at YUAG, I earned my M.S. from the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation in 2013 with concentrations in Objects Conservation and Preventive Conservation. During and before my graduate studies, I also completed internships at The British Museum (London, England), the American Museum of Natural History (New York, NY), the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia, PA), and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (Williamsburg, VA).

Growing up, what type of career did you envision yourself in? Did you think you’d work in an art museum?

In college, I actually majored in Neuroscience! I thought for a very long time that I wanted to be a scientist or a medical doctor. But as soon as I learned that the field of conservation existed (which combines many different types of science with art and art history in very exciting ways), I completely changed paths.

What skill set are you most proud to bring to the DMA?

I have really enjoyed the work I’ve done in preventive conservation (or the prevention or delay of deterioration of cultural heritage). I look forward to continuing this work at the DMA. Recently, I have participated in research related to Oddy testing (used for selecting materials for an object’s storage or display that have the most ideal ageing properties), anoxic treatment methods for pest management, and environmental pollutant monitoring.

What is your favorite thing about being a conservator?

I love that my job allows me to interact with collections in ways that often shed new light on an object’s history or an artist’s work, which continually enables me to keep learning. I feel lucky to be part of a field that also serves to share this information and connect the public with cultural heritage and works of art. I am so thrilled to work at the DMA and I very much look forward to working with and learning from the staff and the collections!

Fran Baas is the Associate Conservator at the DMA