Ghosts, jack-o-lanterns, spider webs—these are some of the things that come to mind when thinking about Halloween. But the most important of all might be candy! I love how there is no shame in eating as much candy as I like this time of year. I must admit, sweet treats are on my mind a lot—so much so, that I couldn’t help but make some sugary connections with our collection.

Candy dish, Louis Comfort Tiffany (maker), date unknown, iridescent glass, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nelson Waggener, 1983.18

If the title of this piece is not enough to spark your imagination, maybe the gorgeous color of Tiffany’s candy dish will. Tiffany may be best known for his stained glass windows, but his creative versatility was also renowned. Lamps, vessels, jewelry—you name it, he could do it. The iridescent glass on this dish reminds me of old-fashioned pulled taffy, delicately thinned out into a flower-like shape, or an unraveled, satiny candy wrapper inviting us to share its saccharine delights.

Dale Chihuly, Hart Window, 1995, glass, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Linda and Mitch Hart, 1995.21.a-ii, © Dale Chihuly

Speaking of glass, Dale Chihuly’s blown glass sculpture is an iconic installation commissioned for the Hamon Atrium. One of my fellow interns shared a story of a little girl who disagreed that Chihuly’s piece was made of glass. She asked the young girl what she thought it was, to which the girl answered, “plastic.” I was hoping she was going to say candy, because that’s what I think of every time I pass by. The vibrancy of the colors and the seemingly soft forms make me think of fruit roll-ups.

Pendant: macaw head profile, Mexico or Guatemala, Maya, 600–900 CE, Dallas Museum of Art, given in memory of Jerry L. Abramson by his estate, 2008.76

This Maya pendant of a macaw head profile has me dreaming of a flavorful lozenge. When viewed in person, this jadeite pendant pops out from the gallery’s gray walls, almost as if glowing. It’s no wonder that the Mayans valued jadeite and other greenstones as some of their most precious materials, just like diamonds are to us.

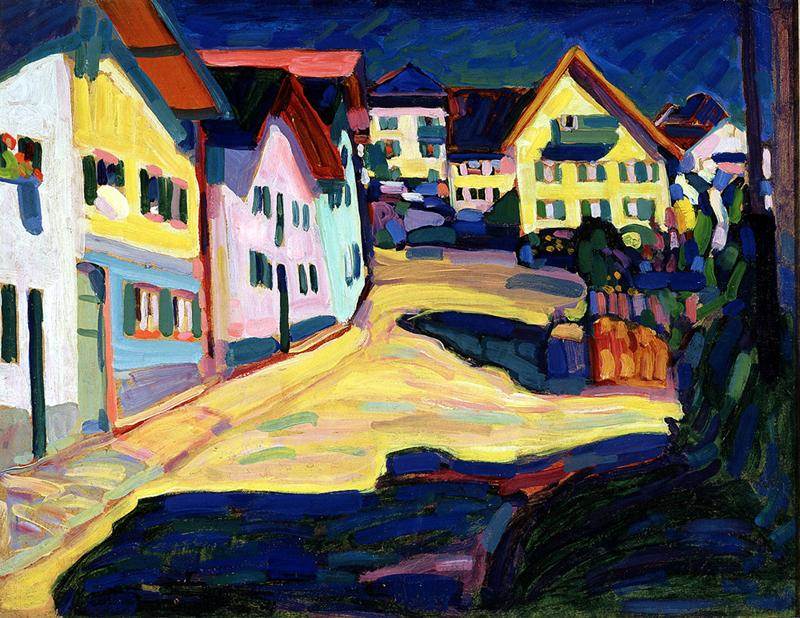

Wassily Kandinsky, Murnau, Burggrabenstrasse 1, 1908, 1908, oil on cardboard, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1963.31

Wassily Kandinsky had a neurological condition called synesthesia, a rare phenomenon in which one sense simultaneously triggers another sense. In Kandinsky’s case, he saw colors when he heard music. I like to think that I taste things when I look at art, but that’s not really true. This landscape painting reminds me of Munchkinland from The Wizard of Oz. Can you imagine the sidewalks lined with gumdrops and lollipops?

I blame candy makers for conditioning my brain to associate bright colors with candy, but I hope my connections have emphasized the enchanting qualities of these works of art. Art truly transcends visual response and transforms into palpable sensations, or at least that’s what I tell myself to feel better about my sweet tooth. I encourage you to explore which pieces from the DMA’s collection speak to you.

Paulina Martín is the McDermott Intern for Gallery & Community Teaching at the DMA.