Next time you visit the Dallas Museum of Art, make sure you stop by our Japanese collection. You can find the Japanese gallery on the third floor in the Arts of Africa, Asia, and Pacific Island galleries. In the center of the gallery, you will find three exquisite examples of Japanese lacquer. In fact, one of my favorite works in our collection is a Japanese lacquered Chest of drawers.

History of Japanese Lacquer

According to Monsieur Gonse, a French connoisseur and art critic, “Japanese lacquered objects are the most perfect works of art that have ever issued from the hands of man.”

The art of lacquer actually came to Japan from China around the 6th century A.D. Originally connected with Buddhism, early lacquer adorned the walls of Buddhist temples. As the medium became more popular, lacquer objects became more utilitarian and were primarily used as everyday objects. Individuals who commissioned such decorative objects had to be patient with the time commitment involved, for it could take months to even years to complete a lacquered object.

What makes Japanese lacquer special?

In order to appreciate the true value of Japanese lacquer, it’s important to understand how lacquer objects are made.

Lacquer comes from the sap of the lacquer tree, Rhus vernicifera,and is known as

urushi. Most lacquer forms begin with a wooden foundation, a special wood called Hinoki, a species of Japanese cypress. Before the layering of the lacquer begins, the lacquer artist wraps the wooden object in a silk or hempen cloth saturated with a mixture of lacquer and rice flour called nori urushi. Then, a layer of powdered earthenware mixed with lacquer is applied over the cloth and sanded smooth. This method is applied with finer grades of powder until an even layer is produced.

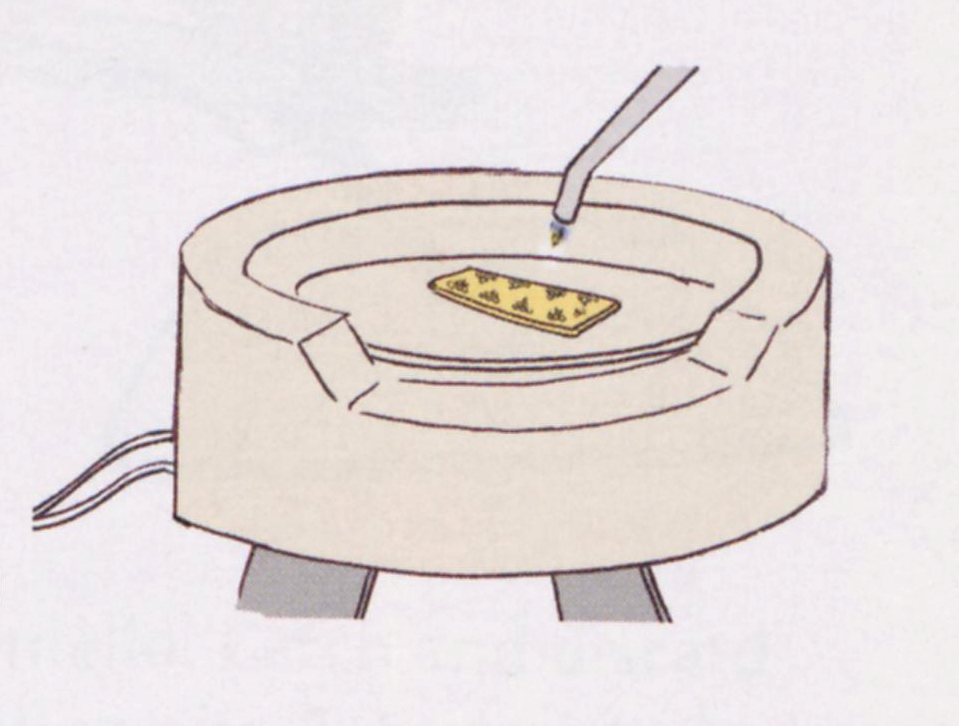

After the foundation layers are smoothed, the object is ready for the refined lacquer. The refined lacquer is blackened by iron and applied carefully in layers. Because the lacquer takes a long time to dry and needs high humidity for hardening, the object is placed in a “wet box” for three to four days before the next coat is applied. After the object is removed from the “wet box”, it is carefully smoothed and polished with magnolia charcoal. This is repeated about thirty to eighty more times until the final coat is applied. After the last coat has dried, the object is finger polished with deer’s horn ashes and oil.

Fun Fact: Because the humidity in Japan is so high, the three lacquered objects here at the DMA are placed in humidity controlled cases.

This precise artform requires a huge amount of skill and patience. If one were to apply thirty coats of lacquer and wait four days in between each layer, it would take up to 120 days to complete the lacquer portion of the object. This is not including any special techniques such as inlay or other carving methods. Altogether, it could take half a year to complete a lacquer object! How long do you think it took to create this Lacquered wood saddle?

Next time you’re at the Museum, come by and see some of the finest hand-made objects in our collection. Once you see these beautifully-crafted objects in person, they are bound to become your favorites!

Over and out,

Loryn Leonard

Coordinator of Museum Visits

Resources:

- Mody, N.H.N., “Japanese Lacquer,” Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Jan., 1940), pp. 291-294

- Weintraub, Steven, Kanya Tsujimoto, and Sadae Y. Walters, “Urushi and Conservation: The Use of Japanese Lacquer in the Restoration of Japanese Art,” Ars Orientalis, Vol. 11 (1979), pp.39-62