This month marks the arrival of the DMA’s new Eugene McDermott Director, Agustín Arteaga. Uncrated sat down with him in the Museum galleries to get to know him a bit better:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bWaVGJksSdk]

Posts Tagged 'DMA'

Meet Our Director

Published September 7, 2016 Behind-the-Scenes ClosedTags: Agustín Arteaga, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, The Eugene McDermott Director

All in a Day’s Work – 1940s

Published September 5, 2016 Archive 3 CommentsTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Labor Day

It’s Labor Day and while it is time to say an unofficial goodbye to summer, it is also the perfect time to recognize some of the staff that worked hard to make the Museum what it is today.

The Museum staff in the 1940s was small. Counting the names on the rosters in bulletins and annual reports, there were fewer than 20 people, including the teaching staff, which is about 10% of the people currently employed by the DMA. Some did multiple jobs covering both administrative and teaching duties, for example, or managing both the library and education programs.

This is Building Superintendent Jimmie Garrett in 1940. He joined the staff after working on the construction crew that built the Museum in 1936. Unfortunately, I can’t quite figure out what he is doing in the photo, maybe guarding an installation in progress, or maybe just pondering the small figures on the shelves.

Ed Bearden, in the coat and tie, was both the Museum’s Assistant Director and a member of the teaching staff. Here, he instructs a sculpture class with a live model in 1946.

The 1947 State Fair was an exciting time as the Museum secured a loan of Rosa Bonheur’s famous painting The Horse Fair from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and staff worked hard to promote the event.

Mary Bywaters (left) and Fran Bearden (right) use The Horse Fair to promote Dallas Art Association membership. The man in the center is unidentified, but it would be great to learn his name if you recognize him.

In addition to administrative and art class teaching duties, Ed Bearden also gave public lectures. Here he is speaking about The Horse Fair in 1947.

Standing left to right: Herb and Jett Rogalla, Ed and Fran Bearden, Mellville Mercer, Jeanette Bickel, Rusty Grimes, Barbara Mercer, Margaret Milam; seated left to right: Jerry Smith, Mary Bywaters, Tom Grimes.

Thankfully it wasn’t all work for our 1940s staff. Here are some DMFA staff and friends in what I like to imagine was a staff picnic-type outing, but maybe I am reading too much into the grass and trees in the picture. It would be quite a happy coincidence if the photo happened to be taken on Labor Day 1948.

Stay tuned next Labor Day to see Museum staff of the 1950s doing interesting things . . .

Hillary Bober is the Archivist at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Party in the DMA

Published August 31, 2016 Behind-the-Scenes , Exhibitions ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Late Night, mural, Nicolas Party, Nicolas Party: Pathway, Street Art

On August 1, Nicolas Party hopped off the plane at DFW and ever since it has been a Party in the DMA. It only took the Swiss artist two weeks to transform the Museum’s Concourse into an enchantingly surreal landscape. Unconfined to a static sketch, each day the former graffiti artist added richly hued flora that simultaneously recalls forest floors and ocean depths. Visitors were entranced as he worked to bring his imaginative vision of a sanctuary for the people of Dallas to life. Check out the progression of the site-specific mural below.

And tomorrow, let the long weekend begin. Come experience the wonder of Nicolas Party: Pathway on Thursday evening and throw your hands up because we’ll be playing your song when DJ Wild in the Streets takes over the DMA patio. You’ll be nodding your head like yeah as we start the weekend early with 20% off crepes from Socca, fresh retro pop, funk, soul, and great company. See you there!

- Photos of Nicolas Party in action

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H8nUu7NnnIM]

Julie Henley is the Communications and Marketing Coordinator at the DMA.

The Canines Behind the Canvas

Published August 25, 2016 Collections 3 CommentsTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, dogs

Dogs are said to be man’s best friend, but can they also be his muse? The following artists sure thought so! These four-legged friends were never far from their master’s side, eager to give a bark of approval for work well done or a shake of the muzzle to try again, and, in dire circumstances, to lend their tail as an extra paint brush. These furry entourages inspired, encouraged, and lent a paw whenever they could to their famous owners. Happy National Dog Day to the creative canines behind the canvas!

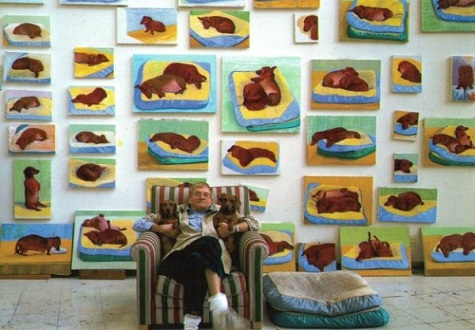

David Hockney with his models, Stanley and Boogie

- Image sourced from: http://anotherimg.dazedgroup.netdna-cdn.com/640/azure/another-prod/240/7/247717.jpg

- Image sourced from: http://barkpost.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/dachshunds.jpg

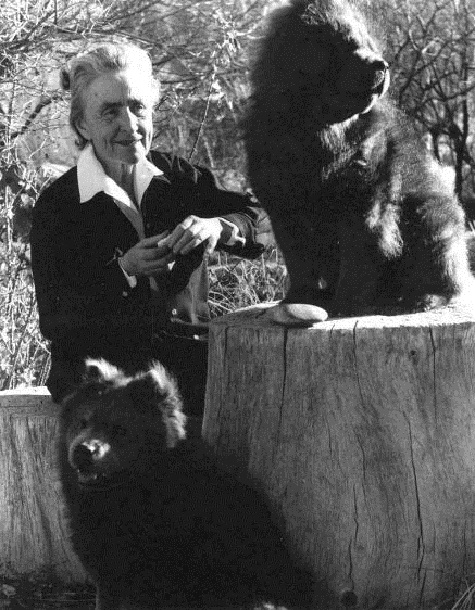

Georgia O’Keeffe getting some air with her fluffy chow companions

- Image sourced from: http://anotherimg.dazedgroup.netdna-cdn.com/909/azure/another-prod/240/7/247681.jpg

- Image sourced from: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/564x/ba/ff/5d/baff5db772172ec50e8d2dc3fb71877e.jpg

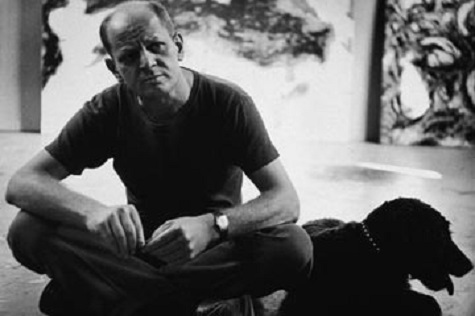

Jackson Pollock taking a breather with Gyp and Ahab

- Image sourced from: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-XdvvND-K0E0/URot44HEYyI/AAAAAAAAAh8/hRQTD5QvWGM/s1600/slide_234313_1129189_free.jpg

- Image sourced from: http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/polljack/reference/AAA_polljack_6337.jpg

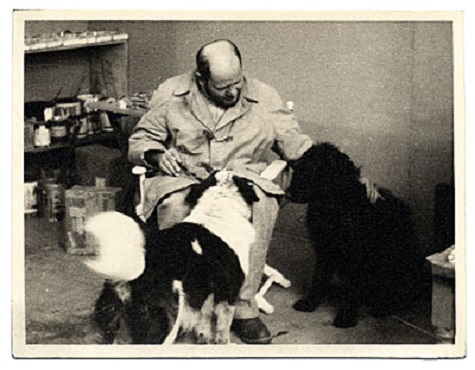

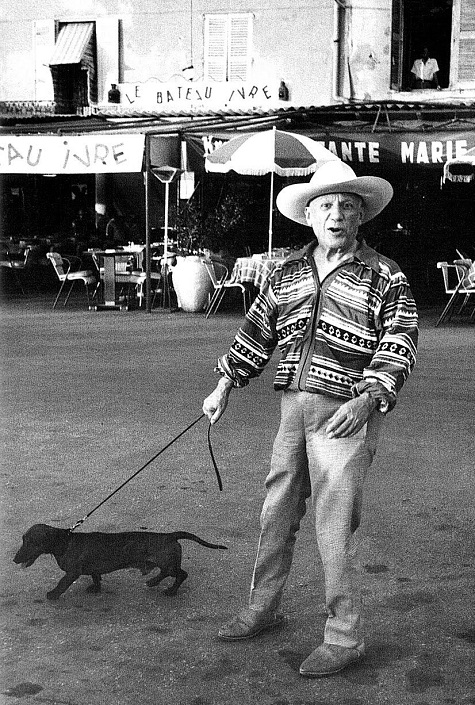

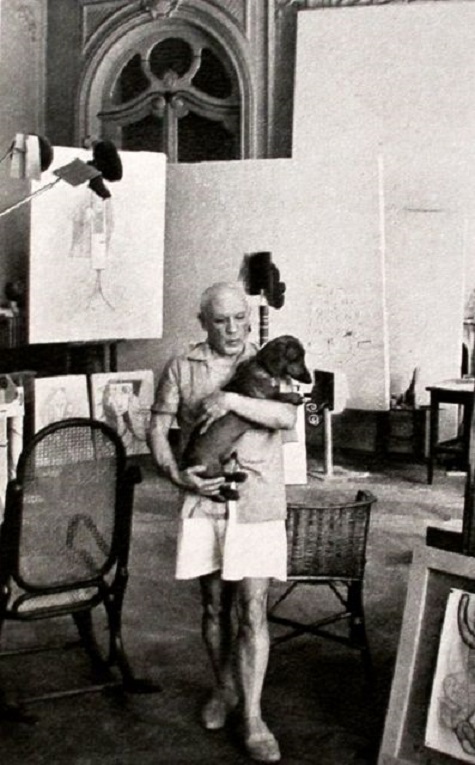

Pablo Picasso adventuring with his beloved dachshund Lump

- Image sourced from: http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5245e2f4e4b0dcb0662f41e3/t/54d3b1e3e4b09df3e6aaee78/1423159782255/

- Image sourced from: http://40.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m7h1y1dJ5A1qew1aoo1_500.jpg

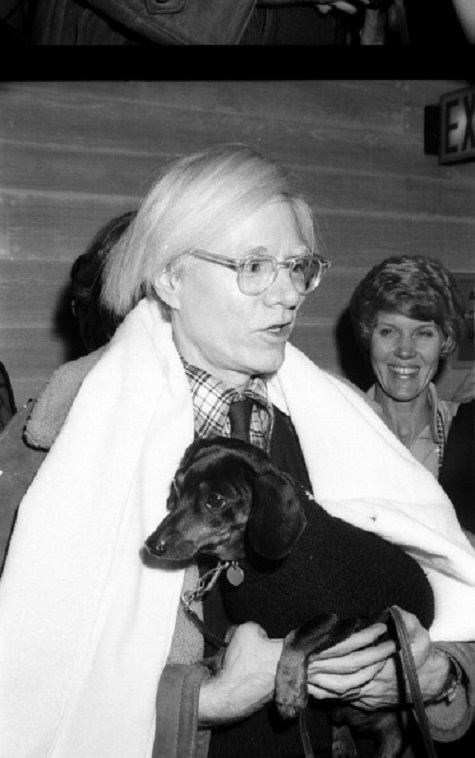

Andy Warhol with his favorite army candy . . . his dachshund Archie

- Image sourced from: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/80/c6/7e/80c67ebf26ba8a1c79d1bf316d298164.jpg

- Image sourced from: http://dijitaldevrim.zorlupsm.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/andy-warhol-hund-488083785.jpg

Frida Kahlo with her hairless, but not heartless, Xoloitzacuintli dogs

- Image sourced from: http://www.radiopaula.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/frida-khalo-and-dogs.jpg

- Image sourced from: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/564x/0c/b7/41/0cb741892b8ad5f1c182be95efcc04ee.jpg

Julie Henley is the Communications and Marketing Coordinator at the DMA.

Appily Ever After

Published August 22, 2016 Behind-the-Scenes , DMA app 1 CommentTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, DMA app, Mobile application, Pariveda Solutions

Once upon a time, in a kingdom called the Dallas Museum of Art, a group of talented young wizards from the nearby land of Pariveda decided to create an enchanted portal. Far better than your run of the mill magic mirror, the portal gave all, far and wide, a glimpse into 5,000 years of the realm’s riches. Royalty and peasants alike could go behind castle lines with specially curated content like audio tours and insider guides, all without fear of being thrown into the dungeon. Word of mouth and carrier pigeons became practically obsolete with the portal’s interactive map, filterable calendar, favorites queue, and instant social media sharing. If that weren’t enough, with a mere shake of their scrolls a random treasure would pop up to explore!

The wizards saw how much joy the portal brought the kingdom and decided to share it with all. They named their creation the DMA app and made it available on iOS devices!

And they all lived APPily ever after . . . Download today to experience the wonder.

Meet the Wizards:

Reed Correa

Texas A&M University, Management Information Systems

Hey there! In building the DMA app, I worked to pull back artwork in the permanent collection, displaying details about that artwork, and displaying tour media information. My favorite work in the Museum is probably the Sporting Cup designed by Ashbee. I came across it while testing the search function. There are a number of cups and they became my favorite search. I love the turquoise color on it!

Philip Gai

Baylor University, Computer Science

Hi! My central tasks in building the DMA app were developing the home page, the exploration guide pages, and the shake for a random art piece feature. After working with so much art information for the guides, I definitely came to appreciate art in a new way. The Wittgenstein Vitrine is definitely my favorite artwork at the DMA!

Nick Graham

University of Oklahoma, Computer Science

Hi! I created the “At the Museum” page, which gives an overview of events on the DMA calendar. Additionally, I worked to make audio-video tour content accessible from the app. I enjoyed the opportunity to work in this unique environment with so many beautiful works of art. During this summer, I have grown to especially like the Wittgenstein Vitrine and Piet Mondrian’s Windmill.

Derik Hasvold

Brigham Young University, Provo, Information Systems

Hi! Helping build the DMA’s mobile app was fantastic. One thing I worked on is the ability to filter through the Museum’s art collection to find artwork you are interested in. This feature helped me realize one thing: I love sculptures! There are some sweet sculptures in the Sculpture Garden; some of my favorites are Willy and Dallas Snake. If it weren’t for this amazing app, this is something I might never have discovered.

Mary Kate Nawalaniec

University of Notre Dame, Electrical Engineering

Hey! I primarily worked on the Map features for the app. During our time at the DMA, Samantha Robinson was gracious enough to give us the history behind the Wittgenstein Vitrine. She provided interesting insight into the process of acquiring and restoring art pieces. I have a greater appreciation for the work curators do to track down pieces like the vitrine. It’ll be hard to top having the DMA as office space!

Julie Henley is the Communications and Marketing Coordinator at the DMA.

But Wait There’s More!

Published August 17, 2016 Arts & Letters Live 1 CommentTags: Arts & Letters Live, Candice Millard, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, Hannah Rothschild, Margo Jefferson, Patricia Cornwell, Robert Hoge, Ross King, Yaa Gyasi

DMA Arts & Letters Live, the Museum’s acclaimed literary and performing arts series, announced a “but wait there’s more!” extension of its 25th anniversary season this week with six author events for the fall.

I’m particularly excited that each of these carefully selected programs dovetails with the DMA’s collection, and we’re offering pre-event tours so that people can explore connections between the featured books and art currently on view.

Here’s the scoop and a few tidbits on why we selected them.

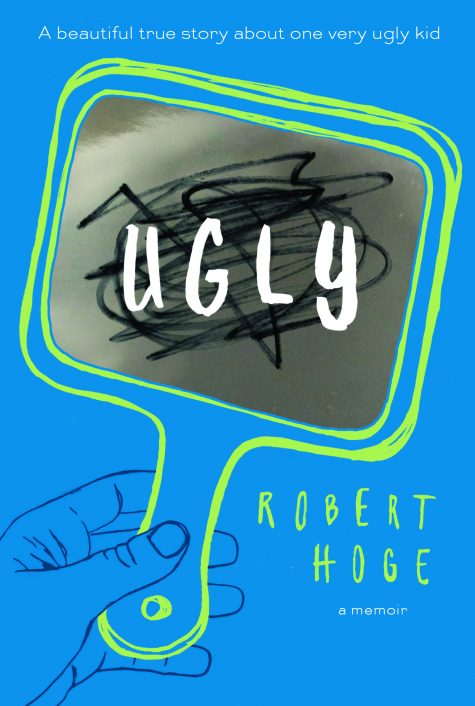

Australian author Robert Hoge wowed us with his TEDx talk, sharing his own poignant and personal story of being born with a tumor on his face and disfigured legs. His memoir for adults and now middle grade students, Ugly addresses life, love, beauty, imperfection, and pain, so his story will resonate with a wide variety of ages. Hoge says, “We all have scars only we can own.” Our pre-event tour will focus on Frida Kahlo’s Self Portrait Very Ugly and stir discussion about self-perception and ideas of beauty.

September 15: Ross King

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1908, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, 1981.128

Ross King returns to the DMA by popular demand with his new book, Mad Enchantment, about the beloved artist Claude Monet and the creation of his famous water lily paintings. He argues that there is more than meets the eye with these serene images of beauty, examining the complexity behind them and the frustrations and challenges that Monet overcame to create them. A docent will discuss the DMA’s iconic painting of water lilies and other Impressionist highlights before the event.

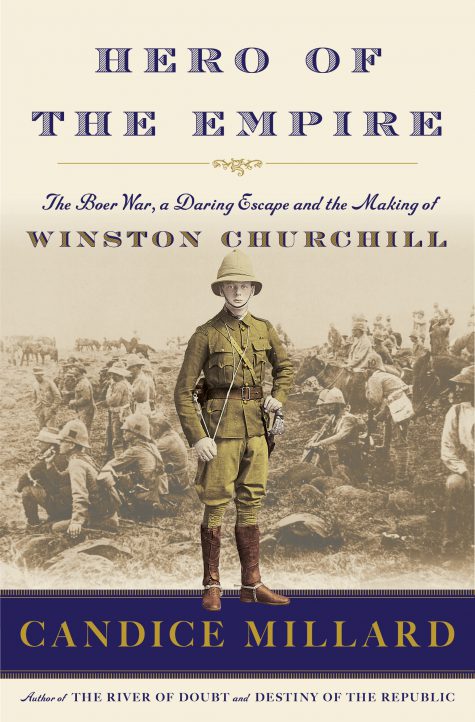

Candice Millard’s brilliant new biography, Hero of the Empire, pinpoints the little-known story of young Winston Churchill’s Indiana Jones–like adventures, including a bold escape from prison camp during the Boer War. Millard offers keen insights on how the lessons Churchill learned in the midst of these challenges related to his achievements and legacy as prime minister later in his life. Before the event, enjoy a gallery talk about Winston Churchill’s friendship with Wendy and Emery Reves and see his paintings and belongings on view in the Reves Collection.

October 26: Yaa Gyasi and Margo Jefferson

One of the most buzzworthy books this summer, garnering more than 250 stellar reviews on Amazon, Yaa Gyasi’s epic debut novel, Homegoing, begins with two half-sisters in 18th-century Ghana—one married off to a wealthy Englishman, the other sold into slavery—and traces the lives of their descendants to 20th-century America. (FYI: Knopf acquired the novel for more than $1 million from the then 25-year-old author!). Pulitzer Prize–winning critic Margo Jefferson adored Gyasi’s novel and will discuss it with her as well as her own National Book Critics Circle Award–winning memoir, Negroland. Before the event, join curator Dr. Roslyn Walker in the galleries to explore works of art from Ghana.

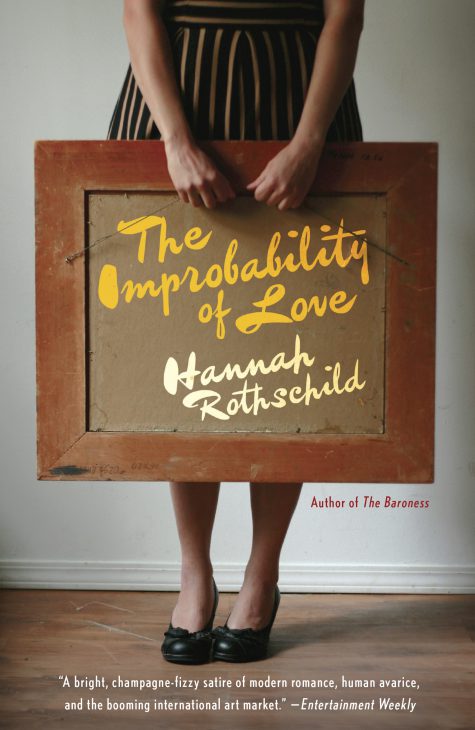

November 15: Hannah Rothschild

British author Hannah Rothschild knows the art world—she comes from a prominent art-collecting family and is the first woman chair of the National Gallery in London. Rothschild is coming to the DMA in her only US appearance for the paperback release of her debut novel, The Improbability of Love. The New York Times hailed it as “a frolicsome art-world caper,” and Elizabeth Gilbert called it “an inspired feast of clever delights.” In it, Annie McDee stumbles upon a grimy painting in a secondhand shop that turns out to be a lost masterpiece by one of the most important French artists of the 18th century. While searching for the painting’s identity, Annie will unwittingly uncover some of the darkest secrets of European history as well as the possibility of falling in love again. Before the event, don’t miss the chance to hear Dr. Nicole Myers, The Lillian and James H. Clark Curator of European Painting and Sculpture, highlight 18th–century French paintings in the DMA’s collection.

November 17: Patricia Cornwell

We’ve had several requests to bring in the #1 New York Times bestselling author Patricia Cornwell on audience surveys, so we are excited to cap off our 25th anniversary season with twenty-five years of Cornwell’s popular high-stakes series starring medical examiner Dr. Kay Scarpetta. Cornwell will share insights about her new novel, Chaos, involving a cyberbully; her creative process in researching and writing her books; and her theory that artist Walter Sickert was Jack the Ripper. Fans can purchase VIP experience tickets that include a wine and cheese reception with the author, a hardcover copy of Chaos, reserved premium seating, and a book signing fast-track pass.

You can make DMA Arts & Letters Live your own book club—invite your friends to join you for these unique and inspiring evenings combining books and art!

Carolyn Bess is the Director of Arts & Letters Live at the DMA.

Freeze Frame

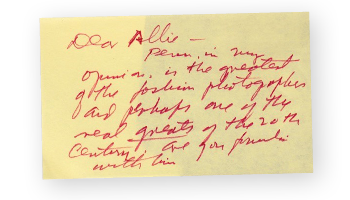

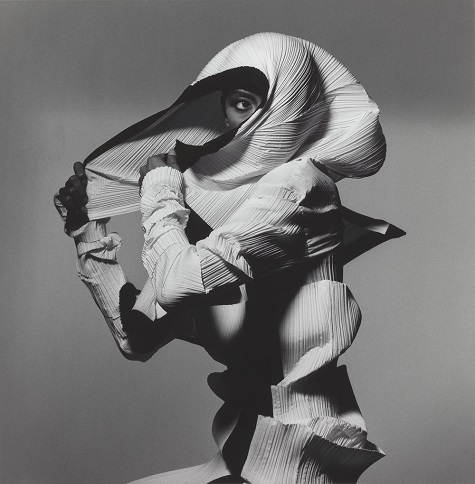

Published August 10, 2016 Artifacts , Exhibitions , Guest Blog Post ClosedTags: Artifacts magazine, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, DMA Members, Irving Penn, Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty, photography

It’s hard to believe, but we’re in the final week of the celebrated exhibition Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty. Prior to the show’s opening in April of this year, Allison V. Smith, photographer and granddaughter of Stanley Marcus, shared with the DMA Member magazine, Artifacts, her first encounter with the work of Irving Penn and the impact of his legacy. Read about her experience below, and discover the work of Irving Penn for the first time or for the hundredth time through Sunday with buy one get on free exhibition tickets offered every day.

One of the Real Greats

By Allison V. Smith

Original publish date: Artifacts Spring–Summer 2016

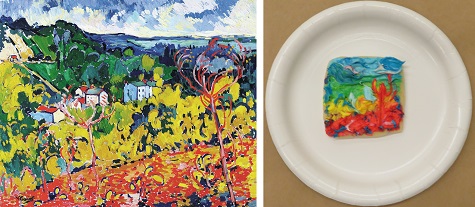

Irving Penn’s name is synonymous with beauty in fashion photography. So it’s no surprise that in 1990 my grandfather Stanley Marcus gave me, a young, passionate photographer, a signed copy of Issey Miyake’s catalogue photographed by Irving Penn. An enclosed handwritten Post-it note read:

“Dear Allie— Penn, in my opinion, is the greatest of the fashion photographers and perhaps one of the real greats of the 20th century. Are you friends with him?”

I wasn’t, but I quickly took the time to educate myself.

Penn’s prolific photographic career spanned seventy years, and in this time he managed to merge the lines between fashion and fine art. His first cover for Vogue magazine was published in 1943, and he would shoot at least 150 more.

Irving Penn, Salvador Dali, New York, 1947, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the artist, © The Irving Penn Foundation

Penn’s assignments ranged from shooting striking models in designer dresses on location in Paris, to contemporary still lifes of familiar objects, to the simple “corner portraits” of artists that included Salvador Dalí and Truman Capote. These portraits were made sometime in 1948 in a constructed corner in his studio. The sitter embraced the corner, demonstrating his or her own personality and making the static background Penn chose into a private stage. Dalí fills the frame in a confident pose, with both arms placed firmly on his knees. Capote kneels on a chair, wearing an oversized tweed jacket and looking directly at the photographer. It’s hard to tell whether he’s feeling vulnerable or safe.

Irving Penn, Truman Capote, New York, 1979, printed 1983, silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation, © The Irving Penn Foundation

Penn wrote in Passage: A Work Record about this process: “This confinement, surprisingly, seemed to comfort people, soothing them. The walls were a surface to lean on or push against. For me the picture possibilities were interesting; limiting the subjects’ movement seemed to relieve me of part of the problem of holding on to them.”

Working for Vogue, Penn had the dream job of traveling the world photographing portraits of everyday people—artisans and blue-collar workers in Paris and London, a gypsy community in Spain, and the tribes of New Guinea. Penn approached all of his portraits with the same respect and elegance as he did in posing a model in Paris or an Issey Miyake design.

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Fashion: White and Black, New York, 1990, printed 1992, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation, © The Irving Penn Foundation

Penn’s photographs are subtle and sophisticated, often finding his subjects against a blank backdrop. His meticulous flowers are a study of visual rhythm. His nudes, whom he shot on countless rolls of film on his Rolleiflex camera between 1949 and 1950, went largely unseen until 1980. He closely examined the shapes of models of all sizes. The results were about form and less about nakedness.

A prolific photographer and a technical master, he made personal work throughout his life, including his early photographs of shop window displays, and later cigarette butts, smashed cups, and chewing gum. These simple photos of litter experimented with different photographic processes, such as platinum and palladium, giving them a rich quality—and also leaving an indelible mark on me.

Allison V. Smith is an editorial and fine art photographer based in Dallas. In 2008, the DMA presented “Reflection of a Man: The Photography of Stanley Marcus,” a retrospective of photographs taken by the department store magnate and produced by Smith and her mother, Jerrie Smith.

State Pride

Published August 1, 2016 DMA Store ClosedTags: Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, DMA Store, Shop DMA, Texas

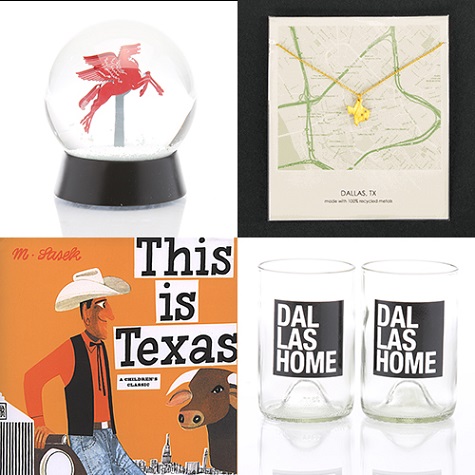

Everyone can admit there is just a certain draw to Texas. We aren’t sure if it’s the Art, Bar-B-Que, or the Cowboys, but we love Texas and we’ve picked our favorite back to school gifts for you to show off your state pride. All are available online and on-site at the DMA Store.

Pegasus Snow Globe – Decorate your desk with this red Pegasus that has come to represent the city since it first flew over the Magnolia Oil Company building in 1934.

Gold Texas Necklace – This custom gold necklace is a delicate way to show your state pride.

This Is Texas by Miroslav Sasek – The stylish, charming illustrations, coupled with Sasek’s witty, playful narrative, make this book a perfect souvenir that will delight both children and adults.

Dallas Home Glass Set – Cheers to loving Dallas! This glass set makes a great addition to any home.

Let Them Eat Cake!

Published July 13, 2016 Arts District , Dallas , European Art , Late Nights , Uncategorized ClosedTags: Bastille Day, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA, French Art, French Revolution

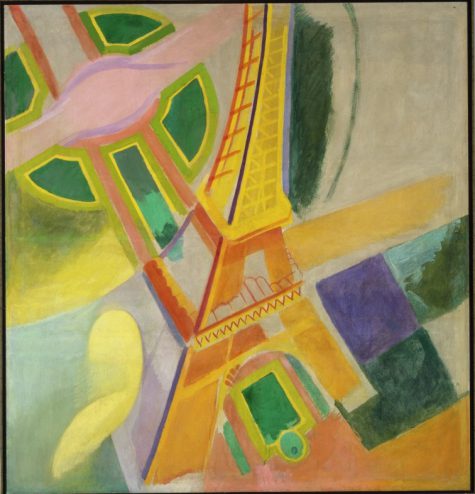

Robert Delaunay, Eiffel Tower, 1924, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, 1981. 105, © L & M Services B. V., Amsterdam

Bastille Day is this Thursday, but the revolution will last an extra day as we continue the festivities during our July Late Night.

To help you practice your French numbers, here are some things you can experience that evening:

Un – The number of movies starring Kirsten Dunst that will be screened (spoiler alert: it’s Marie Antoinette).

Deux – The number of people facing off against each other in our fencing and dueling demonstrations.

Trois – The number of hours DJ Wild in the Streets will spin a mix of eclectic French music.

Quatre – The number of tours that will explore the French Revolution, fashion, and portraiture.

Cinq – The number of hours you can hear live French music performed by local musicians.

Six – The time that Late Night starts, so don’t être en retard!

Sept – The start time for our Late Night Talk sharing a quick history of the French Revolution.

Huit – The number of selfies you should take in front of French portraits in our Rosenberg Collection, and then share them on our Instagram with #DMAnights.

Neuf – The number of rogue mimes you might see walking around.

Dix – The number of times DMA staff might yell “vive la DMA!” during the evening.

Jean Antoine Theodore Giroust, The Harp Lesson, 1791, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, Mrs. John B. O’Hara Fund, 2015.10.FA

In addition to our Late Night, Bastille Day Dallas will expand its annual celebration and bring more French culture to the Dallas Arts District with outdoor activities on Flora Street. So put on your beret, grab a baguette, and join us!

Stacey Lizotte is Head of Adult Programming and Multimedia Services at the DMA.

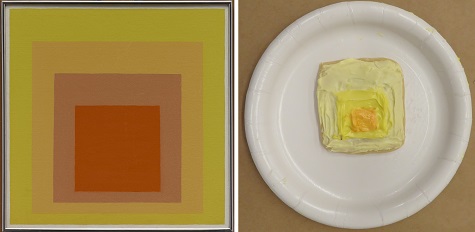

In the DMA’s Education Department, we embrace opportunities to refresh our minds and spark our creativity. And when said opportunities happen to present themselves in the form of baked treats, well, you can bet we’re all over it.

So in honor of National Sugar Cookie Day on Saturday, July 9, I whipped up a batch of blank cookie canvases for my colleagues to craft, with one simple caveat: creations must be inspired by works of art at the Museum.

As the frosting settled and the miniature masterpieces took shape, only one question remained—when can we eat!

- Irving Penn, “Girl Behind Bottle (Jean Patchett),” New York, 1949, printed 1978, platinum-palladium print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the artist, © The Irving Penn Foundation

- Vincent van Gogh, “River Bank in Springtime,” 1887, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene McDermott in memory of Arthur Berger, 1961.99

- Henri Matisse, “Ivy in Flower,” 1953, colored paper, watercolor, pencil, and brown paper tape on paper mounted on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, 1963.68.FA, © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

- Josef Albers, “Study for Homage to the Square: Joy,” 1964, oil on masonite, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Roscoe DeWitt, 1966.12, © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

- Mark Rothko, “Orange, Red and Red,” 1962, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Algur H. Meadows and the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, 1968.9, © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

- Ceremonial mask, Peru, north coast, Sicán culture, 900-1100 C.E., gold, copper, and paint, Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc, 1969.1.McD

- Jasper Johns, “Device,” 1961–62, oil on canvas with wood and metal attachments, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The Art Museum League, Margaret J. and George V. Charlton, Mr. and Mrs. James B. Francis, Dr. and Mrs. Ralph Greenlee, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. James H. W. Jacks, Mr. and Mrs. Irvin L. Levy, Mrs. John W. O’Boyle, and Dr. Joanne Stroud in honor of Mrs. Eugene McDermott, 1976.1, © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

- Natalia Goncharova, “Maquillage,” 1913-14, gouache on paper, Dallas Museum of Art, General Acquisitions Fund ,1981.37

- Robert Delaunay, “Eiffel Tower,” 1924, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, 1981.105, © L & M Services B. V., Amsterdam

- Claude Monet, “Water Lilies,” 1908, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated, 1981.128

- Raymond Jonson, “Composition 7—Snow,” 1928, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Duncan E. Boeckman, 1984.12.FA

- Vincent van Gogh, “Sheaves of Wheat” (detail), July 1890, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection, 1985.R.80

- Maurice de Vlaminck, “Bougival,” c. 1905, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection, 1985.R.82

- Wraparound skirt (“kain panjang”): cloud design (“megamendung”) (detail), Indonesia, Java, c. 1910, handdrawn batik on commercially woven cotton, Dallas Museum of Art, Textile Purchase Fund, 1991.58

- Wreath, Classical or Hellenistic period, 4th century B.C.E., gold, Dallas Museum of Art, Museum League Purchase Funds, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., and Cecil H. and Ida M. Green in honor of Virginia Lucas Nick, 1991.75.55

- Georgia O’Keeffe, “Grey Blue & Black—Pink Circle,” 1929, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 1994.54, © The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

- Dressing set (scent-bottle), attributed to Charles Gouyn, St. James’s Factory, London, England, c. 1755, gold-mounted, porcelain with enamel decoration, Dallas Museum of Art, The Esther and Karl Hoblitzelle Collection, gift of the Hoblitzelle Foundation by exchange, 1995.22.10

- Lynda Benglis, “Odalisque (Hey, Hey Frankenthaler),” 1969, poured pigmented latex, Dallas Museum of Art, DMA/amfAR Benefit Auction Fund, 2003.2, © Lynda Benglis / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

- “Nocturne” radio (model 1186), Walter Dorwin Teague, Sparton Corporation, Jackson, Michigan, designed c. 1935, mirrored cobalt glass, satin chrome steel, and wood, Dallas Museum of Art, The Patsy Lacy Griffith Collection, gift of Patsy Lacy Griffith by exchange, 2004.1

- “Window with Starfish,” Louis Comfort Tiffany, Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, New York, New York, c. 1885–95, glass, lead, iron, and wooden frame, Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., 2008.21.2.McD

- Brooch, Gerd Rothmann, n.d., steel and acrylic, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Edward W. and Deedie Potter Rose, formerly Inge Asenbaum collection, gallery Am Graben in Vienna, 2014.33.283, © Gerd Rothmann

- Frida Kahlo, “Self-Portrait Very Ugly,” 1933, fresco on plasterboard, private collection, © Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society, New York

Sarah Coffey is the Education Coordinator at the DMA.