As you may know, The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece: Masterworks from the British Museum, featuring key works from the collection of Greek and Greco-Roman masterpieces at the British Museum, is currently on display at the DMA. This exhibition, on view through October 6, highlights many representations of the human body and invites us to consider how beauty is defined. Greeks believed that one’s physical, outward appearance was a reflection of one’s inner character—if one was outwardly beautiful, one must also be inwardly virtuous. The body was of utmost importance, and the physical was strongly linked to the moral in Greek minds and culture.

Marble statue of a discus thrower (diskobolos), Roman period, 2nd century AD, after a lost Greek original of about 450–440 BC, from the villa of the emperor Hadrian at Tivoli, Italy, © The Trustees of the British Museum (2013). All rights reserved.

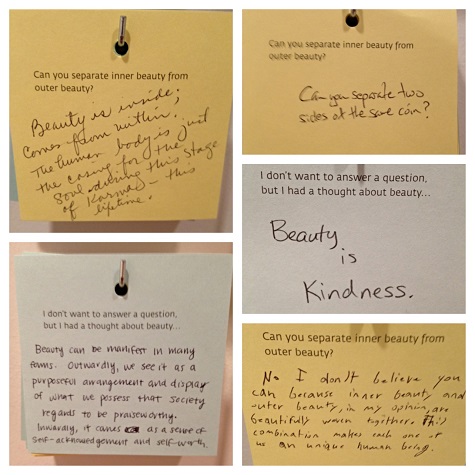

Now, almost two thousand years later, how much have our ideas about beauty changed? Looking at the stunning Diskobolos, do you believe that physical beauty reflects virtue? Or do you think that inner and outer beauty are independent of one another? And how much are your ideas about beauty a product of the culture in which you live? Because the DMA believes that art should spark further thought and discussion, at the end of The Body Beautiful exhibition we created a visitor response wall, where visitors can share their thoughts about beauty after experiencing the exhibition. The response wall consists of two different cards that visitors may choose to fill out—one asks, “Can you separate inner beauty from outer beauty?” and the other reads, “I don’t want to answer a question, but I had a thought about beauty…”

As you can see, we’ve gotten some excellent, insightful, and varied comments! We’re keeping track of them, and we’d love for you to respond as well. This month, receive a $4 discount on an exhibition ticket when you purchase online prior to your visit!

Elizabeth Layman is a summer intern at the DMA with Adult Programs and Arts & Letters Live.