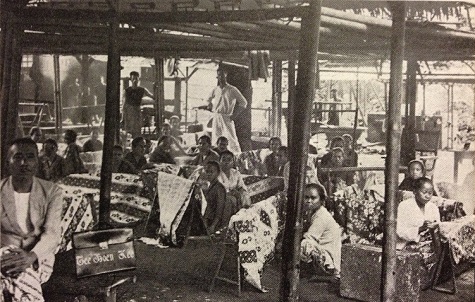

Alexandria Clifton and Kyli Brook are two students of UNT professor Lesli Robertson and both recent grads from the college’s Fibers program. Earlier this year, they set off to research the process of making traditional batik on the island of Java. They were tasked with the challenge (and we are so glad they accepted!) with producing eight batik samples that illustrate the complex creative process of traditional batik makers. These samples will be installed in Waxed: Batik from Java, opening this weekend on Level 3. (Read a little more about the process and the installation in this post.)

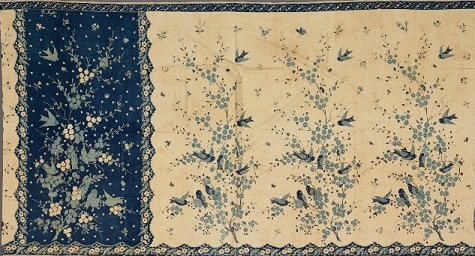

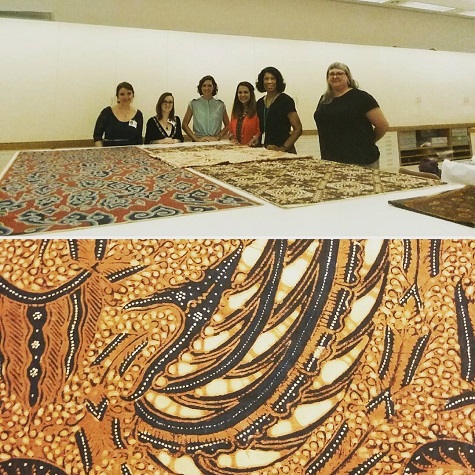

Clifton and Brook’s journey began with a trip to the DMA’s textile storage with curator Roslyn Walker and preparator Mary Nicolett to examine some of the textiles up close and personal. These works are incredibly detailed, and photos alone do not do them justice!

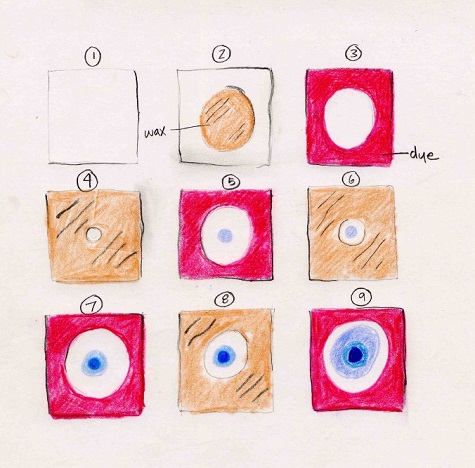

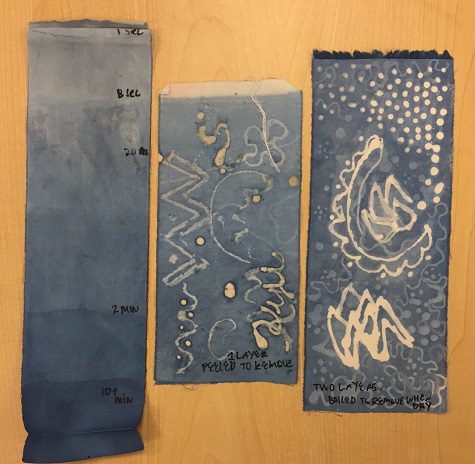

Back in the studio on UNT’s campus, they mixed wax based on traditional Javanese recipes. The wax must be sufficiently durable to resist dye, but also removable. Their research determined that both hand-drawn and stamped batiks involve an initial application of a brittle but easily removable wax mix (klowong) followed by various applications of a stickier, more durable wax mix (templok). The ingredients for hand-drawn wax—their method of wax application—include paraffin, pine resin, beeswax, and fat. Wax for stamp application also includes eucalyptus gum. They used strips of fabric to test out the waxes.

Today in Central Java, indigo dye is generally made from indigo paste, lime, and ferrous sulfate mixed with water. A soga brown dye mixture includes bark from various trees and shrubs. In an effort to be as authentic to the process as possible, Clifton and Brook also used natural dyes for their project. (Learn about UNT’s cool Natural Dye Garden here.)

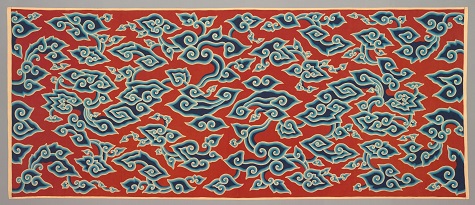

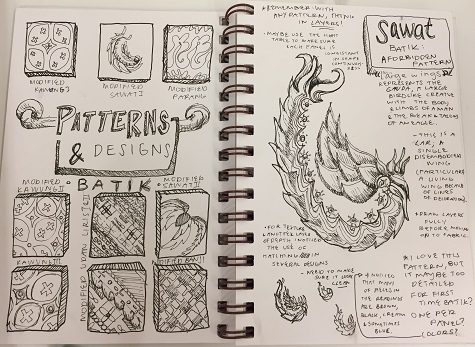

The design of their final eight samples is based on the motif of the red wraparound skirt (kain panjang) with blue clouds (megamenlang). Ultimately, the concentric outlines of this motif more clearly illustrate how to produce gradated hues with subsequent wax applications and dyeing; however, throughout their process the two tested a multitude of designs, all inspired by the DMA’s collection.

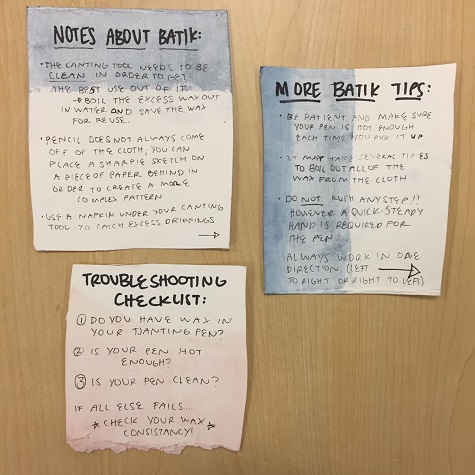

During their research Clifton and Brook compiled a robust binder of samples and experiments and shared it with us. I was particularly impressed because even their notes are lovely!

Not only are Clifton and Brook’s “finished” products on view in the exhibition, but visitors can actually touch and feel the samples. During the fall semester, we look forward to receiving a second set of batiks from Amie Adelman’s class. A HUGE thank you to our friends and colleagues from the UNT Fibers program for another wonderful collaboration!

Andrea Severin Goins is the Head of Interpretation at the DMA.