Opening September 14, Slip Zone: A New Look at Postwar Abstraction in the Americas and East Asia highlights the innovations in painting, sculpture, and performance that shaped artistic production in the Americas and East Asia during the mid-20th century. Find out about the transnational connections between pairs of artworks featured in the show from the exhibition’s curators.

Dr. Anna Katherine Brodbeck, Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art

While the narrative of US art history has focused on the singular achievements of Abstract Expressionism, it did not emerge on the world scene ex nihilo. Rather, US artists drew from multiple precedents, including the Mexican mural movement, which has special resonance for us at the DMA given our longstanding strengths in art from the region. In Slip Zone, Jackson Pollock’s Figure Kneeling Before Arch with Skulls is paired with Crepúsculo by David Alfaro Siqueiros. Siqueiros taught Pollock to use industrial paints at the Experimental Workshop in New York in 1936, which would later inform his use of nontraditional art media in his classic era drip paintings. The expressionistic pathos of this earlier Pollock painting also mirrors the influence of José Clemente Orozco, whose murals he had seen at Dartmouth College the same year.

Images: Jackson Pollock, Figure Kneeling Before Arch with Skulls, about 1934–38, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2017.7, © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; David Alfaro Siqueiros, Crepúsculo, 1965, pyroxylin and acrylic on panel, private collection, © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City

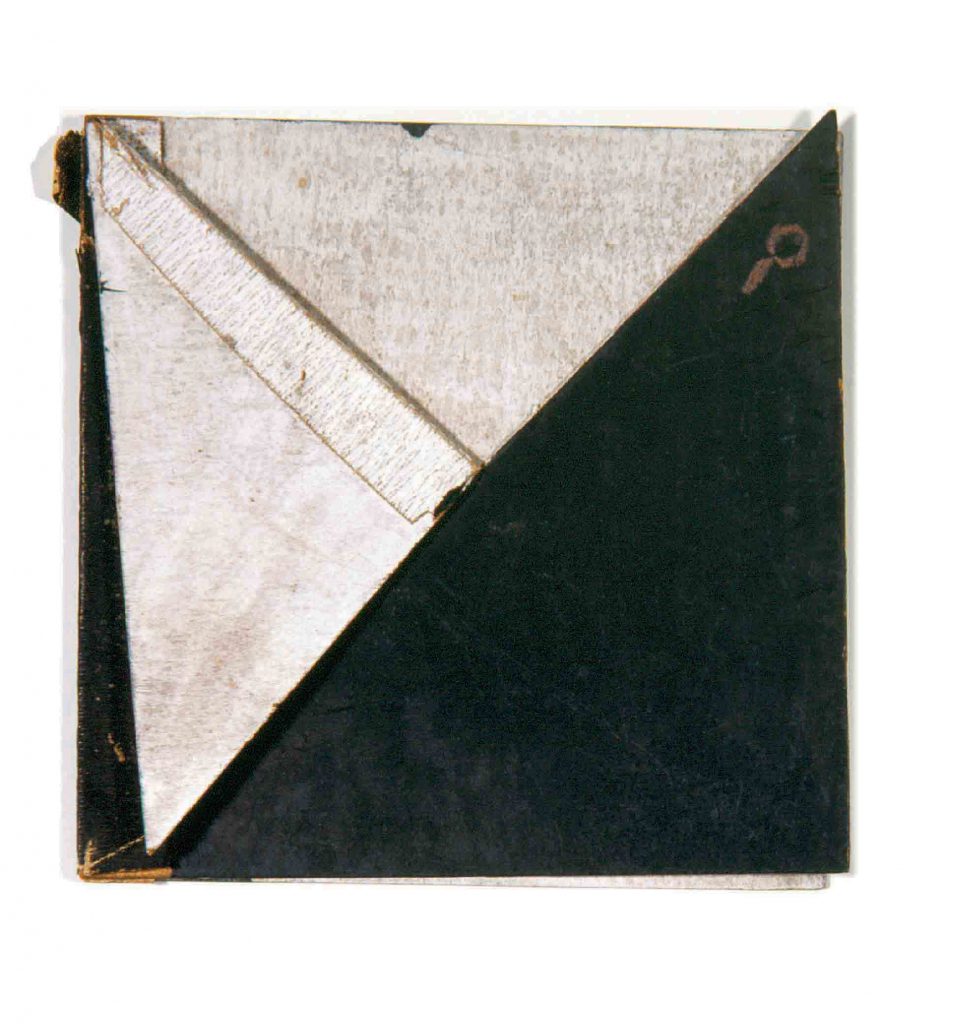

Swiss Concretism promoted geometric art, often using industrially derived materials, which became especially attractive to artists in South America, where it complemented the region’s rapid industrialization. When a sculpture by Swiss Concretist Max Bill won first prize at the inaugural São Paulo Biennial, it had a huge impact on young artists there, such as Lygia Clark. Clark’s Cocoon revolutionized Bill’s use of geometric forms in Rhythm in Space. She takes a layered square, and through a simple action—folding one corner of the black foreground across the composition—she introduces the element of time and irregularity that will be heightened in her later Critters, which have no default form and can be manipulated by the viewer to create multiple configurations. Unlike Swiss Concretism, Clark used organic metaphors to describe these works.

Images: Lygia Clark, Casulo (Cocoon), 1959, acrylic paint and balsam, Collection of Deedie Rose; Max Bill, Rhythm in Space, 1962, granite, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of Mrs. James H. Clark, 1981.91.FA, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Pro Litteris, Zurich

Dr. Vivian Li, The Lupe Murchison Curator of Contemporary Art

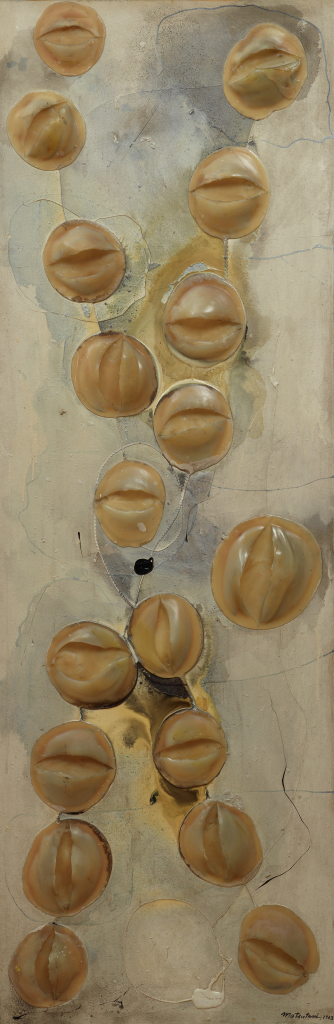

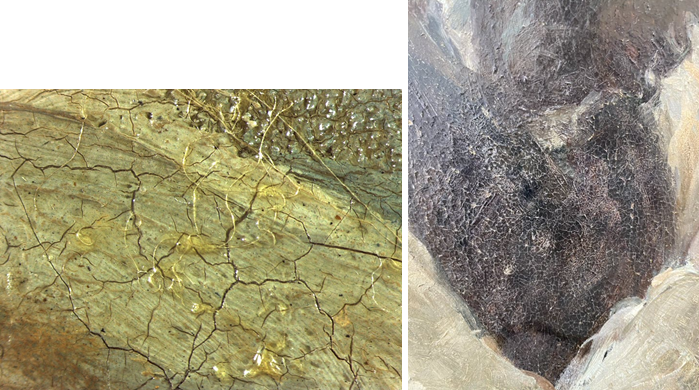

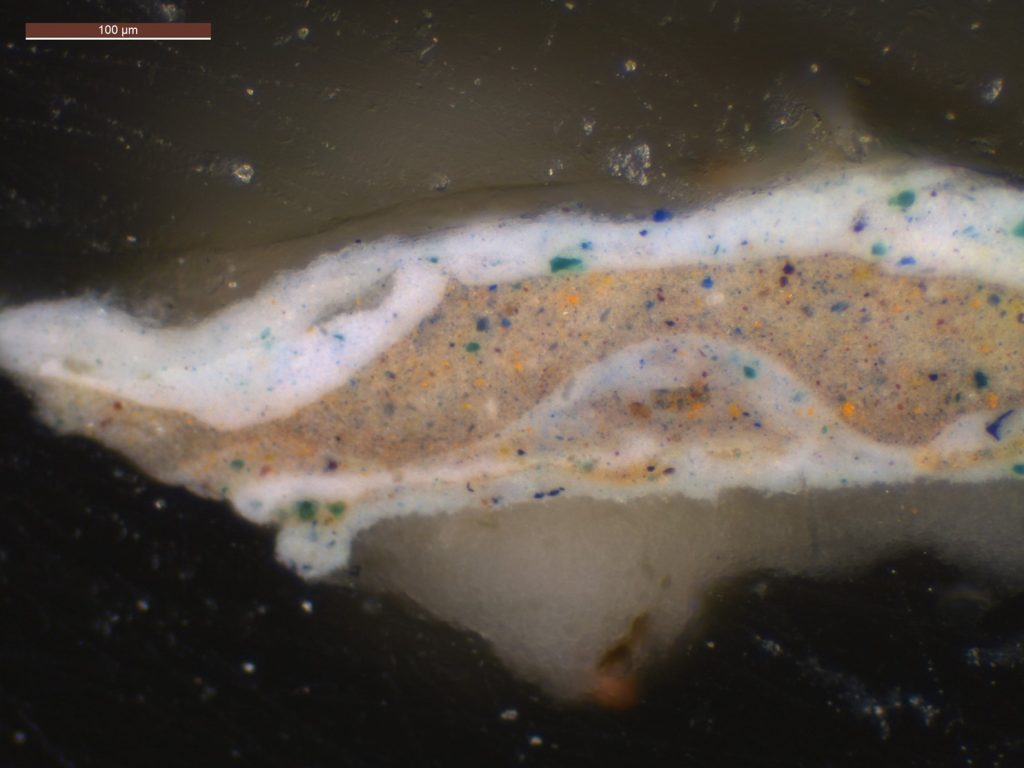

Using a hair dryer and polyvinyl acetate adhesive—commercially available since 1947 as Elmer’s Glue-All—Takesada Matsutani discovered that he could create corporeal, bulbous forms by blowing air into the material from behind until each “bubble” burst. Affixing them to the surface of his paintings, Matsutani constructed uncanny compositions. Similar to Matsutani and other members of the pioneering Gutai collective in Osaka, Robert Rauschenberg sought to blur the distinction between art and life through the use of everyday materials. For his Hoarfrost series, he transferred newspaper images to pieces of diaphanous fabric. After meeting the Gutai collective in 1964, Rauschenberg later collaborated with them, including onstage.

Images: Takesada Matsutani, Work-63-A.L. (The night), 1963, polyvinyl acetate adhesive, oil, and acrylic on canvas, The Rachofsky Collection and the Dallas Museum of Art through the TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2012.1.5. Courtesy the artist. © Takesada Matsutani; Robert Rauschenberg, Night Hutch (Hoarfrost), 1976, ink on unstretched fabric, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the artist, 1977.21, © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

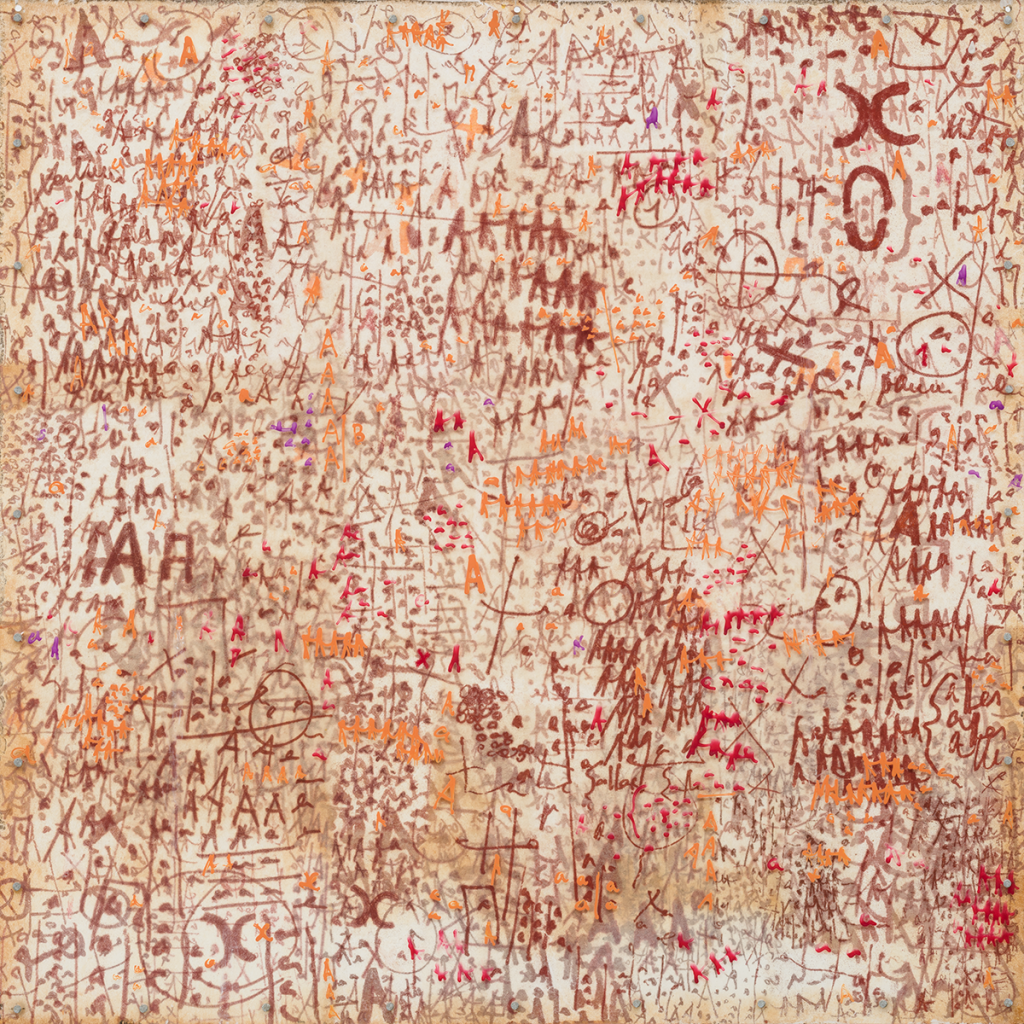

Mira Schendel and Zao Wou-Ki drew upon language and its myriad graphic forms to create intricate works of abstraction. As postwar émigré artists—Zao in France and Schendel in Brazil—both were acutely receptive to the multiple sources of conceptual and material inspiration they encountered, including European modernism, phenomenology, and East Asian philosophy and calligraphy. In 1951, upon seeing Paul Klee’s fascinating use of line while visiting Switzerland, Zao returned to his earlier training in calligraphy to create compositions of atmospheric energy and ecstatic lines. Schendel’s compulsive repetition of icons, symbols, and signs also embraces the spontaneity and transcendent possibilities of language and abstraction informed partly by her interest in Zen philosophy and calligraphy.

Images: Zao Wou-Ki, Dedie a may chan (Dedicated to May Chan), 1958, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Elsa von Seggern because of her love and respect for the arts, 1996.60, © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ProLitteris, Zurich; Mira Schendel, Untitled, 1960s, oil transfer drawing on thin Japanese paper between acrylic sheets, Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman, © The Estate of Mira Schendel. Courtesy the Estate of Mira Schendel and Hauser & Wirth. Photographer: Jeff McLane

Vivian Crockett, Former Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art

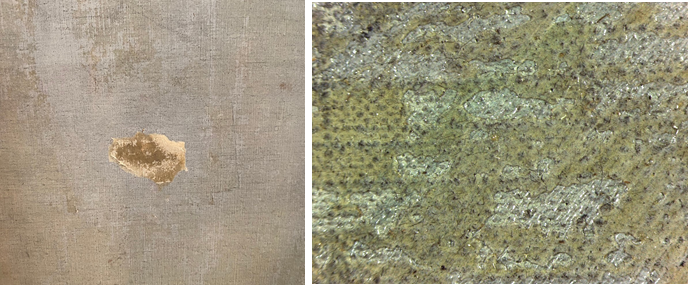

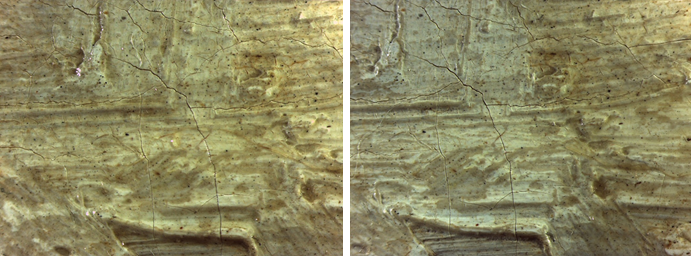

Around 1968 Lynda Benglis began pigmenting large vats of rubber latex with day-glo paint and pouring the dyed materials directly onto the floor. Created after Benglis visited a 1969 Helen Frankenthaler retrospective, this work is a nod to Frankenthaler’s method of pouring paint onto unprimed canvas. A founding member of the Gutai Art Association, Shozo Shimamoto was also deeply invested in experiments with materiality and technique. The artist often incorporated elements of performance in the creation of his paintings, such as throwing glass bottles of paint at the canvas. To produce Untitled – Whirlpool, Shimamoto poured layers of paint onto the canvas, removing the paintbrush as a mediating tool and leaving the final composition to chance and the physical, viscous qualities of the material itself.

Images: Lynda Benglis, Odalisque (Hey, Hey Frankenthaler), 1969, poured pigmented latex, Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2003.2, © 2021 Lynda Benglis / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Shozo Shimamoto, Untitled – Whirlpool, 1965, oil on canvas, The Rachofsky Collection and the Dallas Museum of Art through the TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2012.1.3, © Shozo Shimamoto Association. Naples

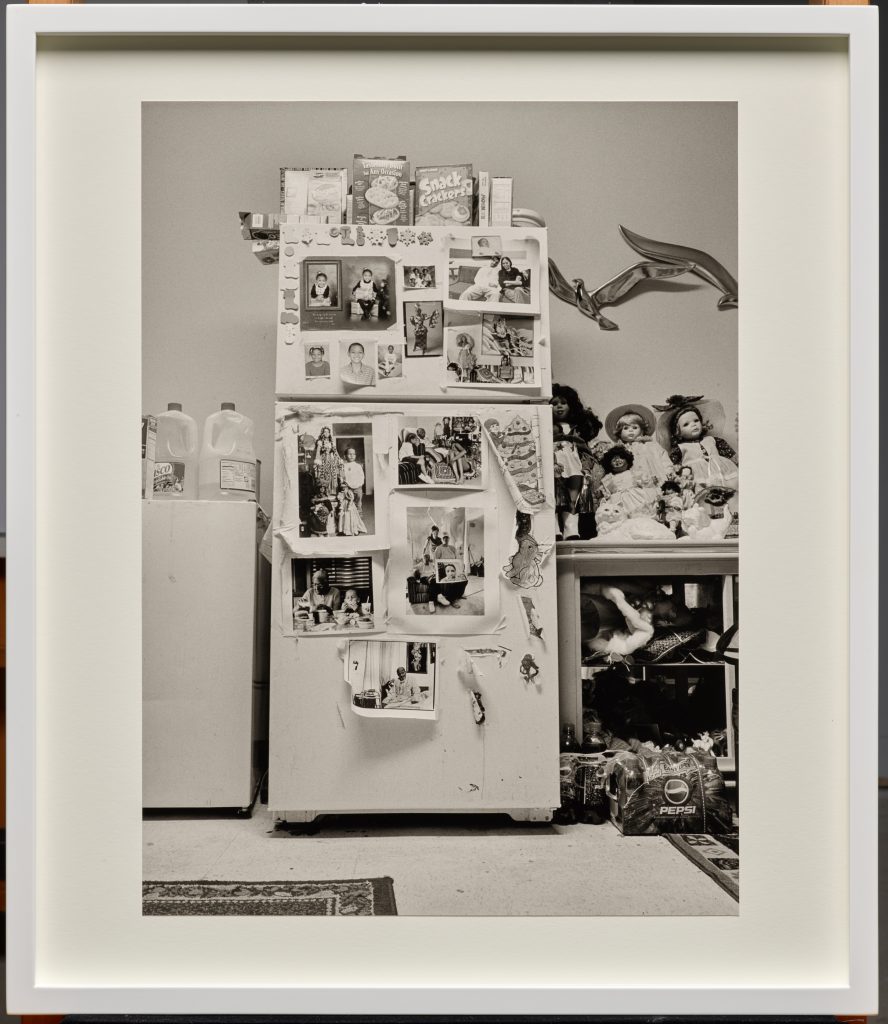

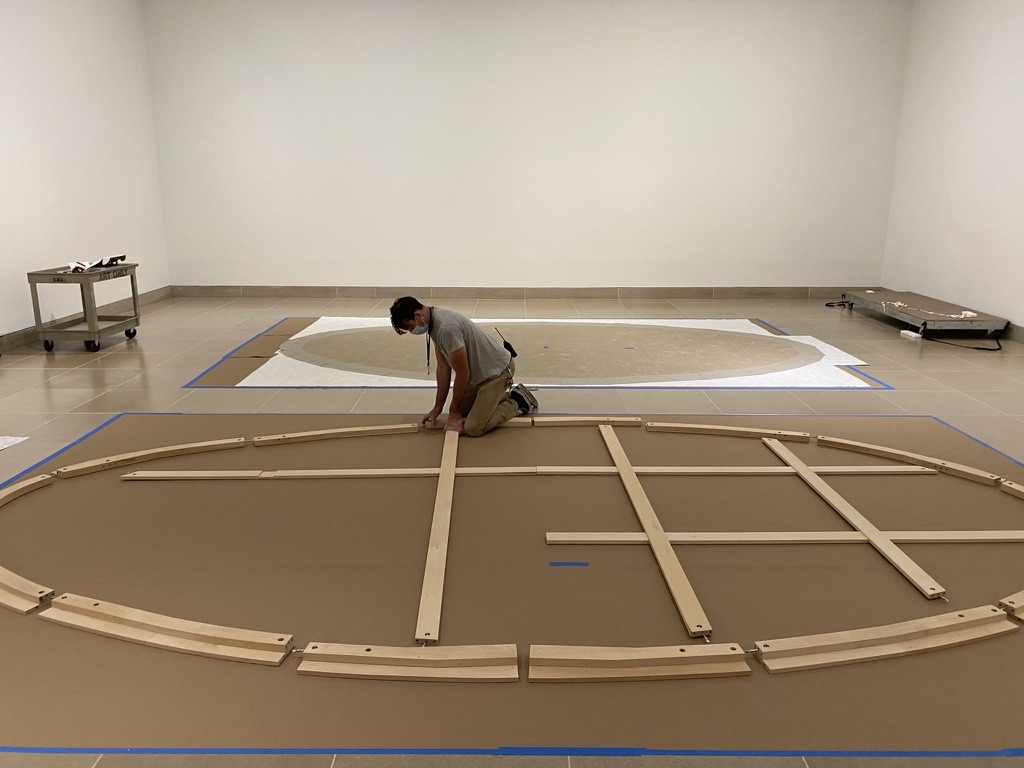

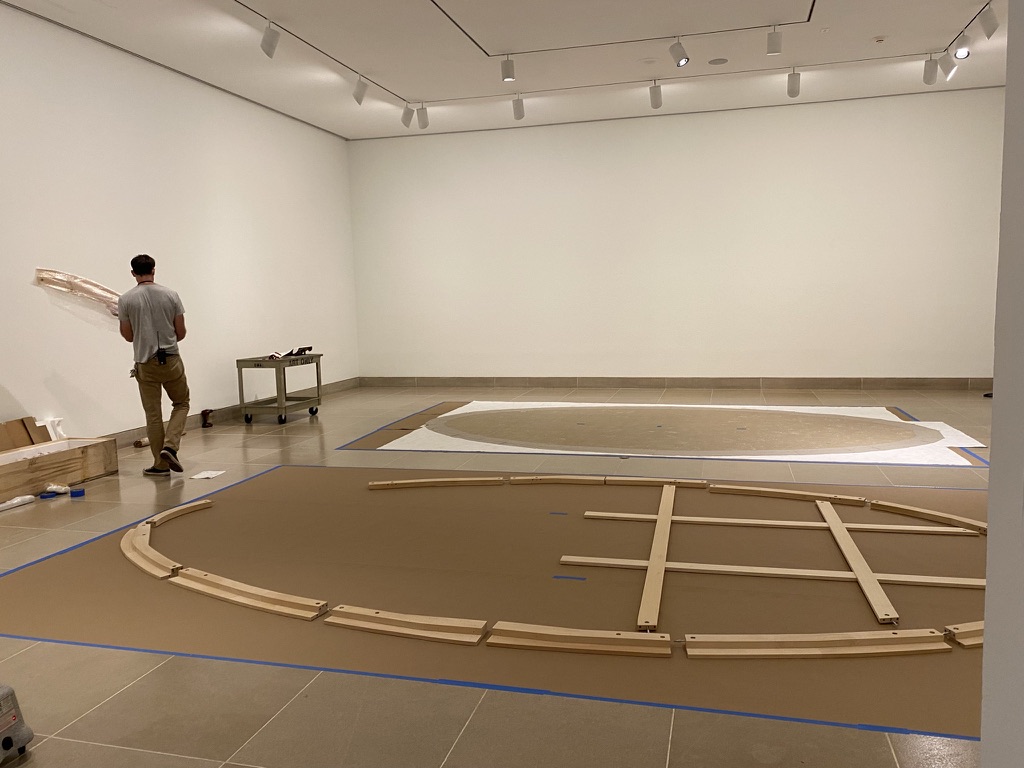

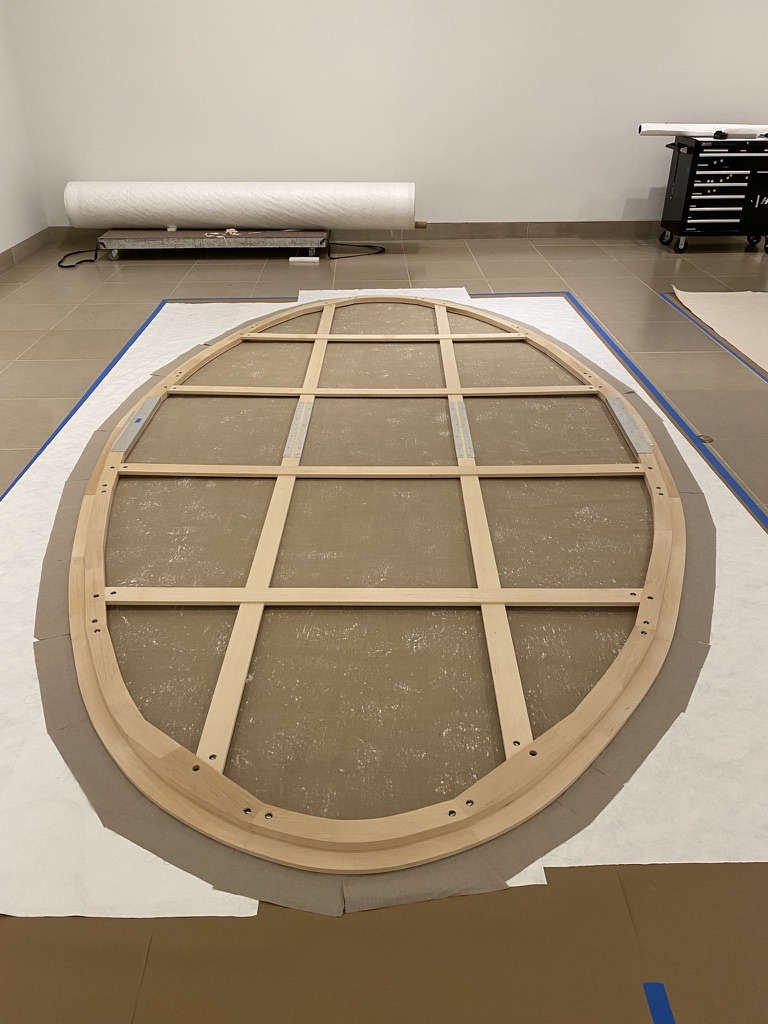

Lygia Clark’s works were one of the main inspirations behind Brazilian theorist Ferreira Gullar’s “Theory of the Non-object” (1959), which described the increasingly blurred lines between painting and sculpture, as well as an overall shift from representational space to physical space. While the theory referred specifically to artists in Brazil, it has many resonances with the works created by Senga Nengudi throughout the late 1960s and 1970s. Both Clark and Nengudi centered interactivity and the use of unconventional materials in their practices. The influence of Sadamasa Motonaga (whose work is also featured in Slip Zone) and his 1956 installation Work (Water) can be felt on Nengudi’s Water Composition, with their shared use of vivid colors, innovative use of materials, and consideration of weight in space.

Images: Lygia Clark, Creature–in itself (Bicho–Em si), 1962, aluminum, Promised gift of Deedie and Rusty Rose to the Dallas Museum of Art, PG.2011.6; Senga Nengudi, Water Composition I, 1969–1970/2019, heat-sealed vinyl and colored water, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund. Simone Gänsheimer. Installation at Lenbachhaus, Munich, via The New York Times