For a Dreamer of Houses takes Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 book The Poetics of Space as its conceptual framework. In this work, the French philosopher posits the house as the formative structure by which we develop a relationship with the exterior world through the emotive qualities of our daydreams and memories. These experiences then become the stuff from which writers and poets spin the threads of meaning, conjuring images forth from where we formed our first world: the house.

The Poetics of Space is, fundamentally, a love letter to poetry, to the ways in which poets shape language into an evocation of lived experiences, of half-forgotten memories. Yet there is a porous boundary between the literary and visual arts, with their shared interest in the conjuring of images. Visual art has a language all its own—one of light captured on silver-coated paper, pixels in digital space, etched impressions. As the resulting weaving of this visual language, art is a way of imagining—and imaging—potential ways of being in the world. In Bachelard’s telling, the questions of being human that art seeks to interrogate and crystallize are forged through the home, the nest from which we learn to become social beings.

Acquisition Fund, 2018.37

For Bachelard, this outward-looking view springs from our sense of the house as a universe in and of itself. In the 2007 photograph Grandma Ruby’s Refrigerator, LaToya Ruby Frazier portrays the home as the encapsulation of a/the world, with the ties of familial relationships proudly displayed in an orderly grid on her grandmother’s fridge. The kitchen—a space of gathering, of shared meals and the tenderness of cooking and providing for one another—becomes the site in which the matriarch orders her world. Here, the home is a place of comfort and love from which her family can fundamentally ground themselves as they venture outside of its sheltering embrace.

Literal depictions of the home are not the only forms of art to which Bachelard’s theories may be applied. Ian Cheng’s BOB (Bag of Beliefs) is an artificial lifeform composed of multiple driving personalities that react to each other and to external stimuli. While BOB lives in a cavernous simulated den in the space of the gallery, viewers contribute to BOB’s development through the BOB Shrine, a phone-based app in which viewers introduce patterns of stimuli to BOB and thereby shape its behavior in a parental fashion. As surprise and upheaval force BOB to update its beliefs, Cheng seeks to explore what constitutes the human experience of change and encounter through artificial life.

BOB exists solely in digital space, an amorphous realm of data that seems almost immaterial in the context of human life. It is through the notion of inhabitation that we ground our relationship to BOB. BOB is not “real” per se, but we are able to conceive of it as a being with drives and needs and to visualize its experience through the framework of the home: its home in the gallery monitors is the place from which it nourishes itself, from which it develops a code of beliefs, from which it interacts with the world on a truly global scale. As Bachelard notes, “Whenever life seeks to shelter, protect, cover or hide itself, the imagination sympathizes with the being that inhabits the protected space.”

It is this ability of the house to foster imagination that Bachelard finds so compelling. He argues that intimate spaces, like those of the home, give rise to the daydreams in which our material, immediate world becomes infinite, and we achieve that grandeur that is only to be found in the depths of thought. The expanse of the cosmos becomes tangible and known, a cherished friend to our imaginings. Bachelard muses, “The house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.”

Perhaps no artist captures the longing and the tender intimacy of the immense better than Vija Celmins, whose lovingly hand-drawn seascapes, rock fields, and starscapes render these seemingly boundless landscapes as human and knowable. Strata, with its soft, luminous stars pulsing through the black field of space, imparts a sense of belonging in a vast universe. In Celmins’s work, we are stardust; “immensity is within ourselves.” Her creation, itself visual poetry, brings the cosmos within our reach, the stuff of daydreams drawn forth from the embrace of the known universe of our homes.

Hilde Nelson is the Curatorial Assistant for Contemporary Art at the DMA.

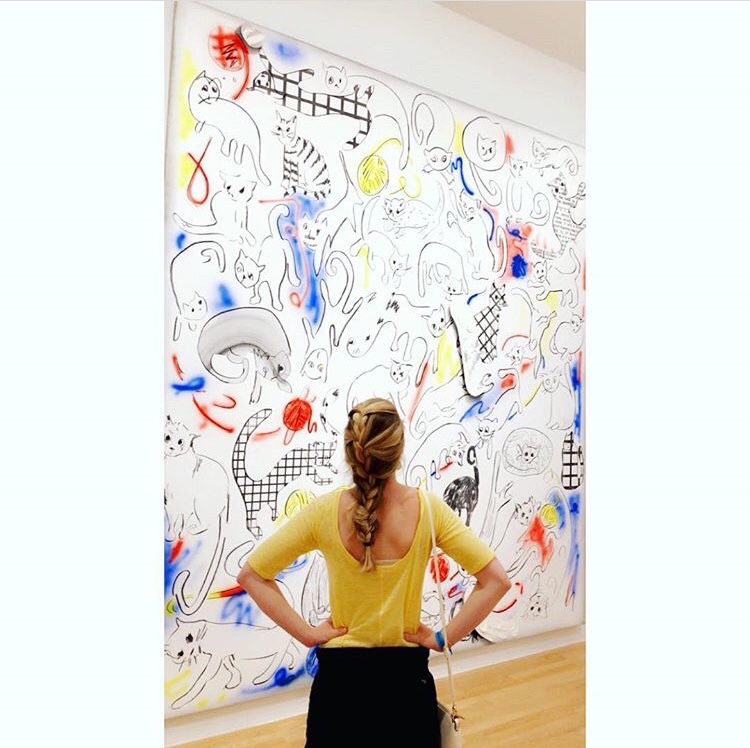

“Laura Owens is an amazing artist; prior to my venture I hadn’t heard of her. But now, I am a fan.” –

“Laura Owens is an amazing artist; prior to my venture I hadn’t heard of her. But now, I am a fan.” –

“Her work is LOUD, quirky, silly, dimensional, full of layers!” –

“Her work is LOUD, quirky, silly, dimensional, full of layers!” – “Exhibición de Laura Owens está llena de color y amor” –

“Exhibición de Laura Owens está llena de color y amor” – “This painting really cat-ures my spirit.” –

“This painting really cat-ures my spirit.” –