As we approach the final weeks of Concentrations 64: Ja’Tovia Gary, I KNOW IT WAS THE BLOOD, I thought I would look back on the process of bringing this exhibition together. Specifically, I’ll walk you through the discussions, installation, and maintenance of In my mother’s house there are many many…, the DMA’s commissioned work from Gary.

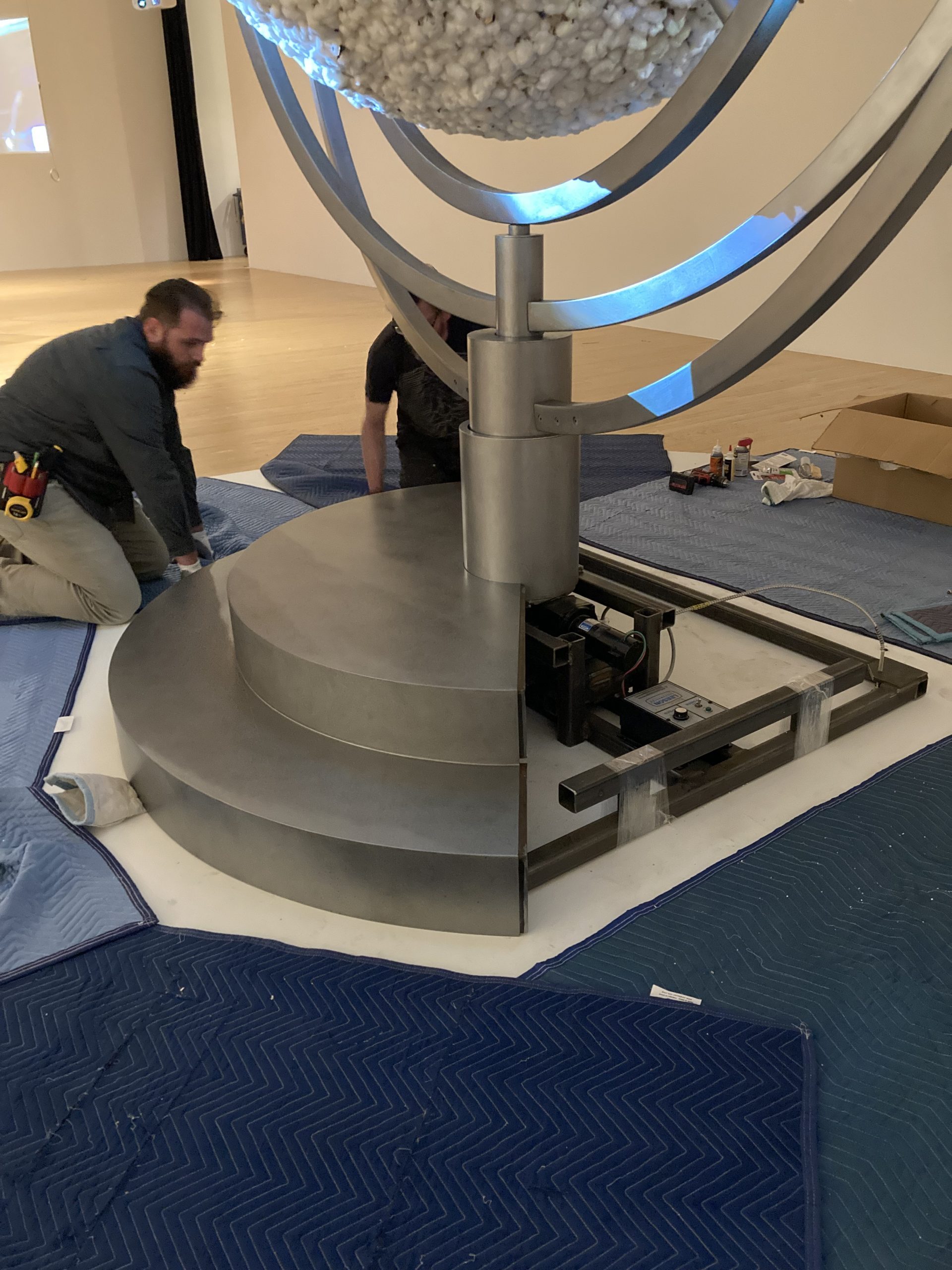

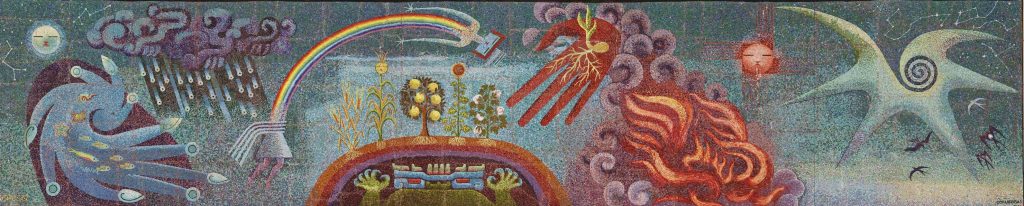

In March 2022, Dr. Katherine Brodbeck, Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art, proposed that the DMA commission and acquire an artwork from Ja’Tovia Gary. Brodbeck and the Contemporary Curatorial Team had been working with Gary on a solo exhibition of her artwork at the DMA as part of our Concentrations series (which focuses on emerging artists), originally proposed by former Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator Vivian Crockett. During these discussions, Gary mentioned a new idea for a project she was interested in designing. The work was modeled after an armillary sphere and would have three metal rings surrounding a large, rotating sphere covered in cotton. A short film composed of excerpts from her upcoming feature-length production would be projected onto the sphere. As part of the DMA’s initiative to be a leader in contemporary art, this proposal provided us with the opportunity to partner with an emerging star in the contemporary art world on a large scale and with exciting new work.

The acquisition of In my mother’s house there are many many… was approved in May 2022, and Gary and the DMA team began to work in earnest on the development of the exhibition and fabrication of the new artwork. The artist partnered with Independent Casting in Philadelphia to construct the armillary sphere. The artwork was new for both Gary and Independent Casting, so it was vital that plenty of time was allocated not just for construction but for hundreds of hours of testing. By April 2023, In my mother’s house there are many many… was ready and shipped to the DMA for installation.

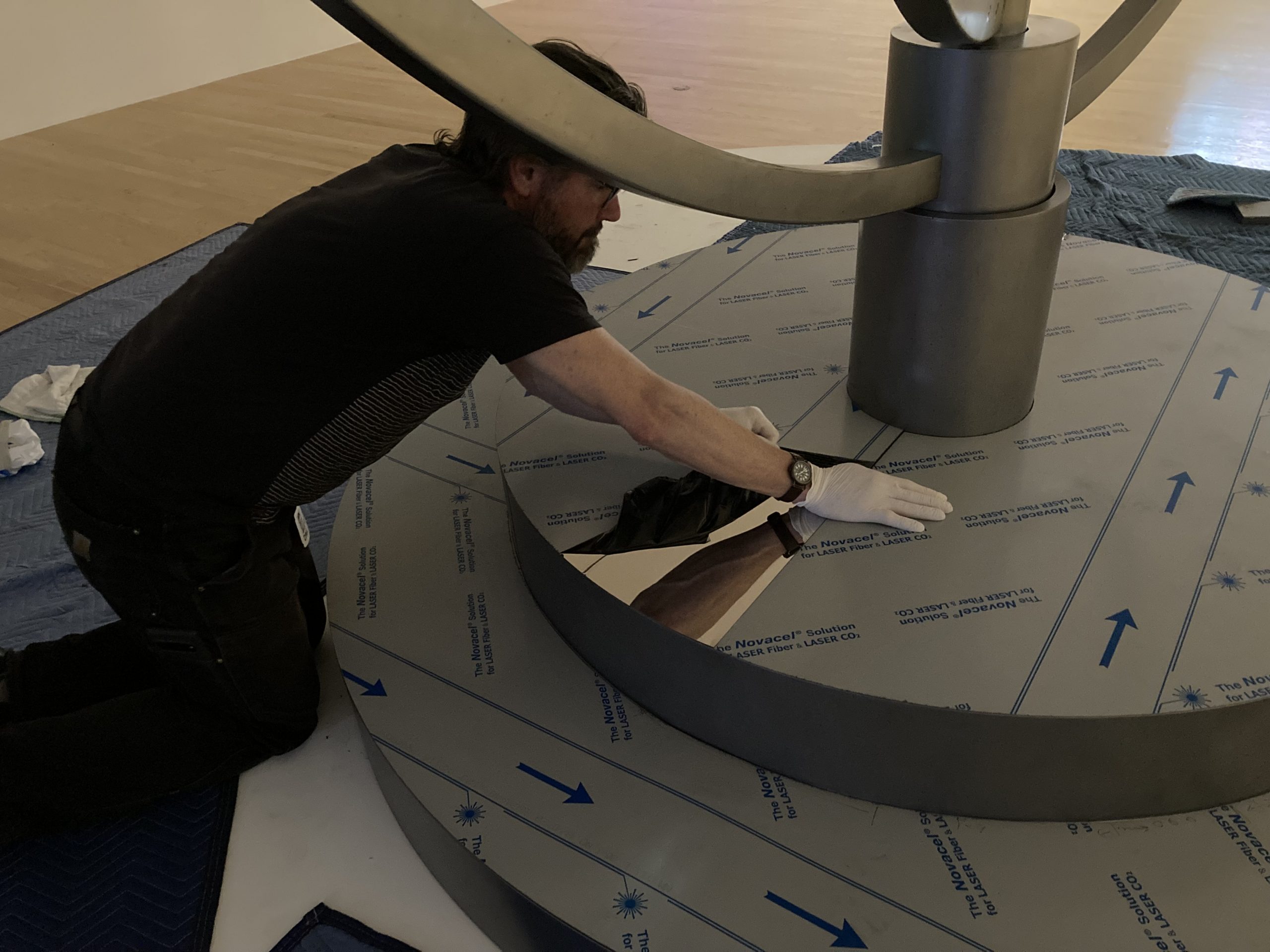

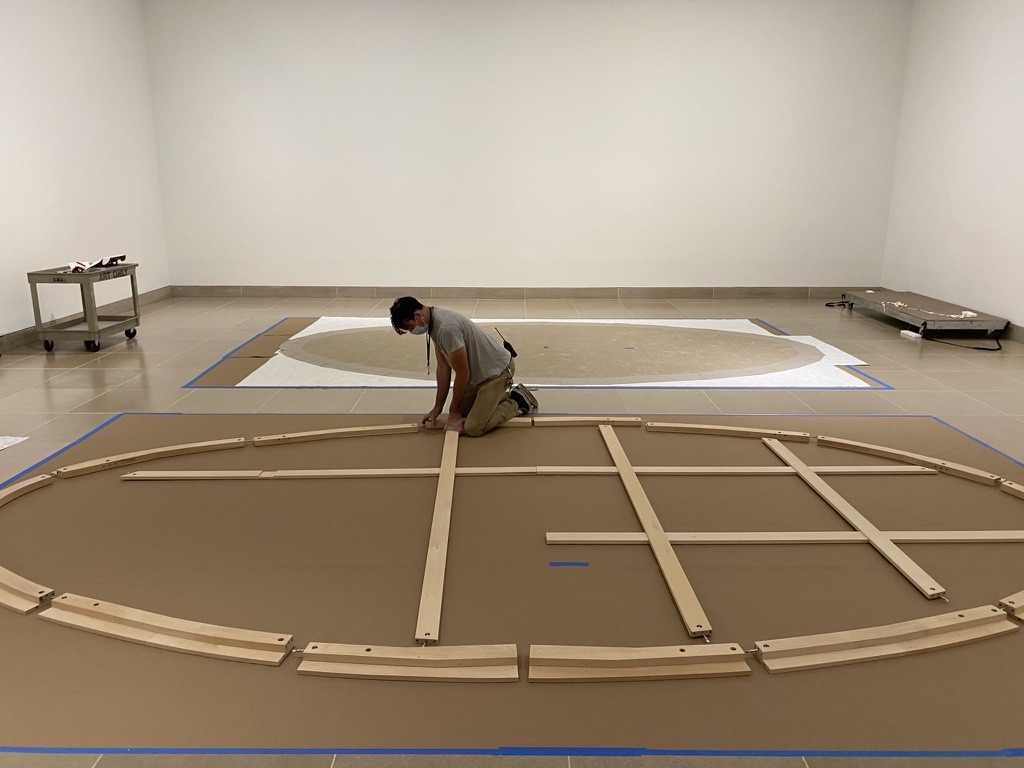

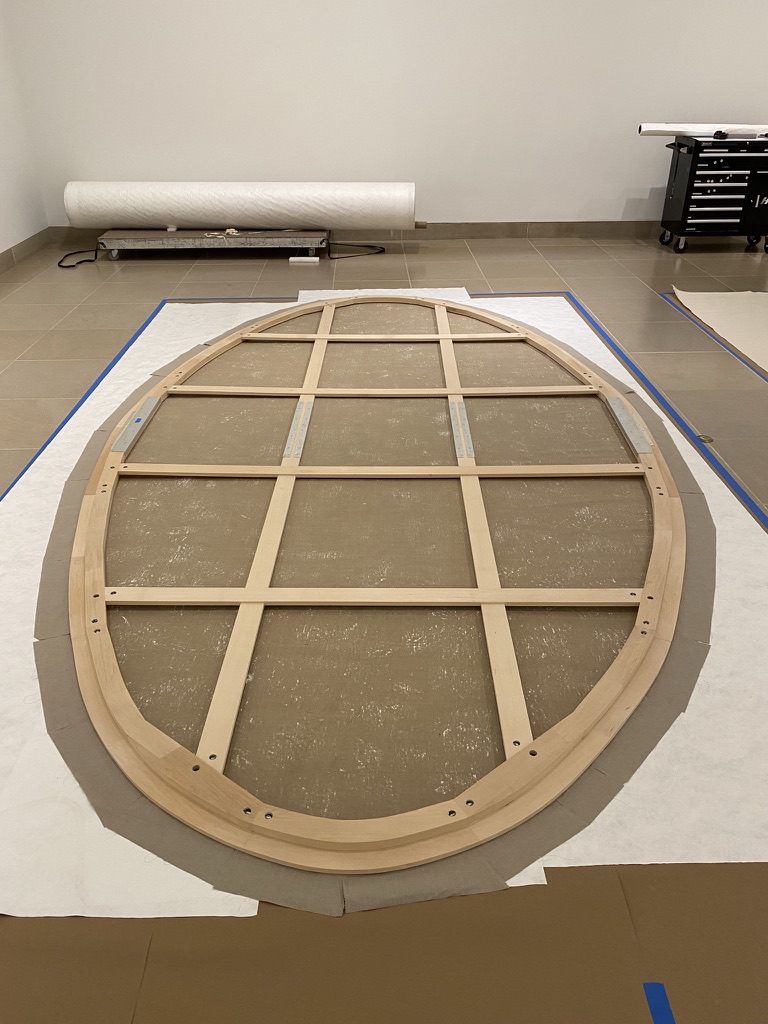

Part of my job as the Associate Registrar for Collections and Exhibitions is to oversee and document the first installation of newly acquired artworks that are considered complex. I take copious notes and hundreds of photographs, and I make sure to document the installation process thoroughly and in a way that will allow for easier installations in the future. As this was the first time In my mother’s house there are many many… was being assembled at the DMA, it was vital that I take good notes in order to write reliable installation instructions.

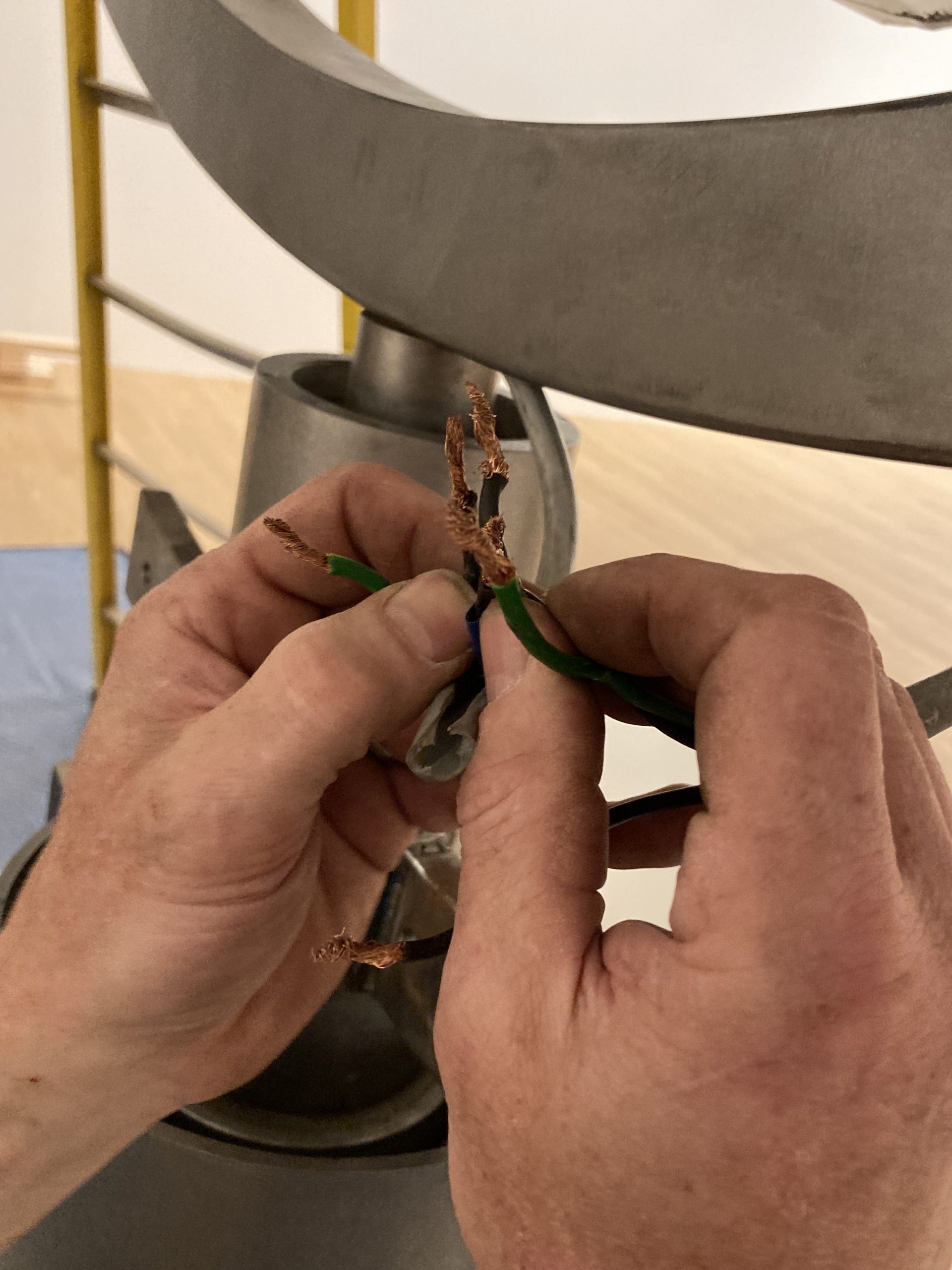

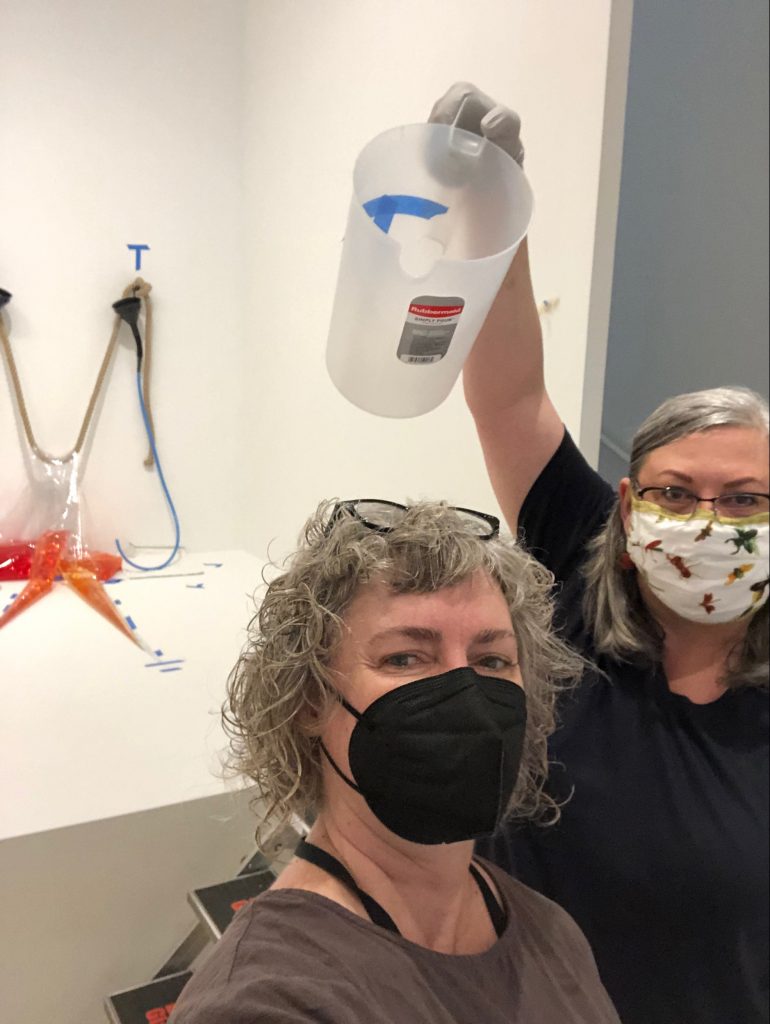

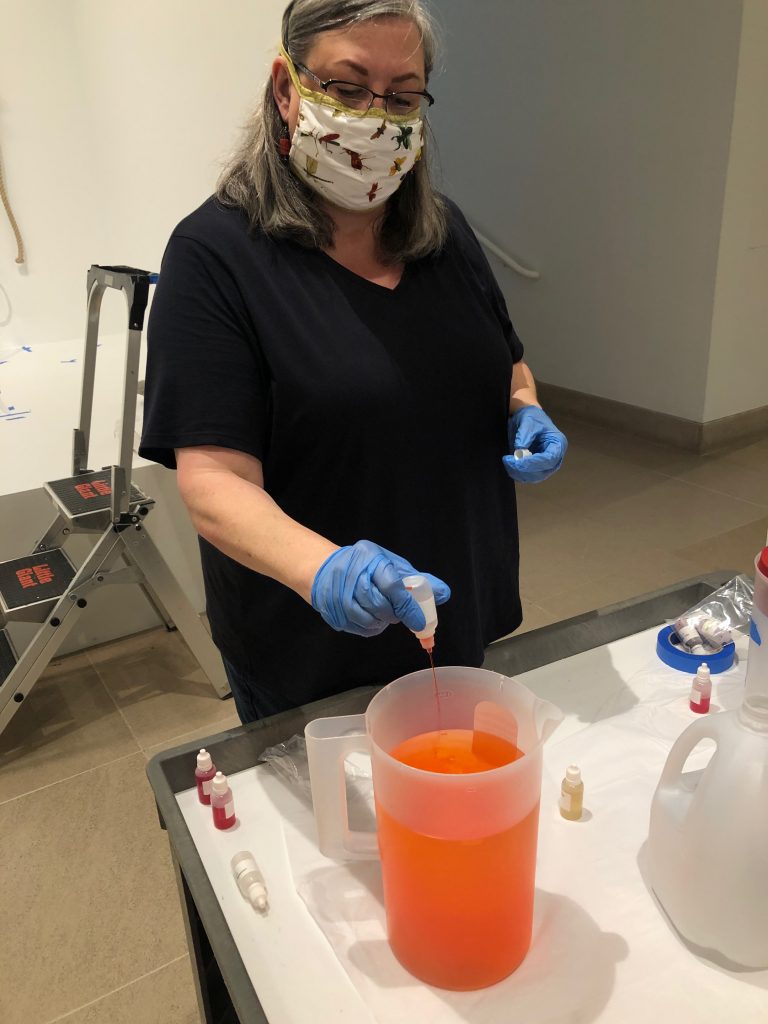

We were assisted during installation by Jonathan Maley, one of the fabricators from Independent Casting. Together, the team installed the piece as shown in the following photographs. Our Senior Manager for Gallery Technology, Lance Lander, worked with Carlin Belkowski of Sensory Innovations on the projectors and the video. They digitally moved the pixels and contoured the projection to precisely fit the sphere using a technique called pixel-mapping.

And, just like that, In my mother’s house there are many many… is up and running!

While it is always the hope that everything runs smoothly once an installation is completed, our team must always be ready to jump in to problem solve if there is an issue. This is especially true of artworks that have motors and moving parts. Since the installation, we encountered a few issues that have required attention. The most significant of these was when the center ring became disengaged from the motor and would no longer turn. Addressing this required much consultation with Gary and the team from Independent Casting, and ultimately required that staff from Independent Casting come out to address the problem. In the end, we got the artwork back up and running, and the DMA team now has a better understanding of how to care for and maintain it.

Working with contemporary art is fun but not without its challenges. Installing a 19th-century painting is certainly more straightforward than installing a newly conceptualized interpretation of an armillary sphere with a video projected onto it! But the fact that the DMA is willing and eager to engage with, cultivate, promote, and support new and innovative artists is part of what makes our institution so special.

Katie Province is the Associate Registrar for Collections and Exhibitions at the DMA.