March is Women’s History Month—a designation that was nationally recognized in 1987 due to the hard work of five California-based women who started the National Women’s History Project (NWHP) initiative. Each year, there has been an annual theme, with this year’s being “Nevertheless She Persisted: Honoring Women Who Fight All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.” This month is an opportune time to think about the pivotal women artists and movements that have affected my practice as an art historian and museum educator.

Throughout Western art history, women artists have been under- and misrepresented in the art canon. These problematic biases against women of all racial and class backgrounds have been discussed by artists, art historians, and activists alike. Through collectives like the Combahee River Collective, organized by black and queer feminists, and the Guerrilla Girls, who produce on-going campaigns against male-dominated exhibitions (and many more!), women have fought and continue to fight for their existence to be known in spaces that downplay their contributions to the art world. Though there has been great work done by curators, art historians, and museum institutions to revise history and work toward a more equal representation of artists, there is still a copious amount of work to be done.

The DMA’s collection boasts a number of women artists, such as Julie Mehretu, Yayoi Kusama, Georgia O’Keeffe, Berthe Morisot, and others. Below are a few artists whose work is currently on view in the Museum who made innovative contributions to the art canon and the world at-large.

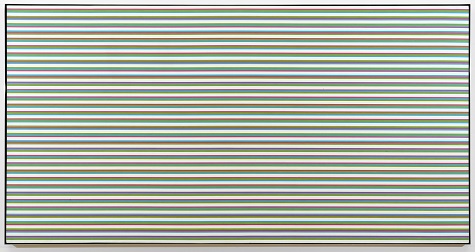

Bridget Riley, Rise 2, 1970, acrylic on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, gift of Mr. and Mrs. James H. Clark, 1976.52.FA, © 1970 Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley is a foundational artist for Op-Art, a style that transformed geometric shapes into optical illusions in order to create a sense of movement. Riley’s name has become synonymous with Op-Art, as her original black-and-white works gained an incredible amount of followers and multiple art prizes in the early to mid-1960s. In the latter part of the decade, Riley explored using colors in her works of art, like Rise 2, to further add elements of instability and illusionistic movement.

Riley’s works of art inspired and infiltrated 1960s pop culture, most notably the fashion industry with the black-and-white houndstooth checkered print seen in the popular mod aesthetics of the time. Due to Riley’s captivating work and popularity, this fashion trend continues to hold weight, as Vogue highlighted Riley in a editorial titled “Why 60s Op-Art Painter Bridget Riley Is the Secret Muse of the Fall 2014 Runway.” Although her work influenced the style of the 1960s, Riley did not enjoy the commodification and commercialization of her art.

Renee Stout, Fetish #1, 1987, monkey hair, nails, beads, cowrie shells, and coins, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Roslyn and Brooks Fitch, Gary Houston, Pamela Ice, Sharon and Lazette Jackson, Maureen McKenna, Aaronetta and Joseph Pierce, Matilda and Hugh Robinson, and Rosalyn Story in honor of Virginia Wardlaw, 1989.128, © Renee Stout, Washington, D.C.

Renee Stout’s move to Washington, DC, in 1985 had a monumental affect on her artistic practice as she sought to understand her identity as a Black-American woman. Her time in DC exposed her to the arts of Western and Central Africa, particularly the Kongo peoples’ nkisi nkondi power figures, an example of which is on view in our African galleries. Through these healing power figures, Stout explores the ritualistic and spiritualistic sides of a possible ancestral tie to the African continent, as seen in Fetish #1. Within this object there are many additive and textural components, as there are with nkisi nkondi figures; however, Stout’s object lacks facial features, adding a mysterious quality that mirrors her feelings toward her personal ancestral past. Click here to learn more about Stout and this work of art in one of the DMA’s Gallery Talks.

Raquel Forner, Apocalypsis, 1955, oil on composition board, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1959.47

Although born in Buenos Aires, Raquel Forner spent a majority of her childhood in Spain due to her father’s Spanish heritage. During this time, Forner became interested in the arts and began training back in her birth city. While briefly teaching at the National Academy of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires, she exhibited across the city, with her first solo show in 1928. After traveling back and forth between Europe and South America in the 1930s, she started to borrow ideas from the Surrealism movement, such as distorted perspectives and figures; however, Forner was not interested in interpreting her dreams like Surrealist artists—she wanted to apply these distorted forms to real world situations such as the 1936 Spanish Civil War and the 1955 Argentine social uprisings. The latter event influenced her Apocalypse painting, where she created abstract land forms and overlapping movement of figures to highlight the confusion and negative aspects human conflict creates. This painting was exhibited in the landmark 1959 exhibition South American Art Today at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, the predecessor of the DMA. Fifteen works of art from the exhibition were later purchased by the DMA, and nine of those works can currently be seen in the Latin American Gallery, including Forner’s Apocalypse.

Yohanna Tesfai is the McDermott Graduate Intern for Gallery and Community Teaching at the DMA.